When I meet Christopher Marney in the café/bar at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, it seems a very apt spot to be discussing his next audacious venture. Marney is about to relaunch London City Ballet – a company that has lain dormant for almost thirty years.

Christopher Marney, Artistic Director of London City Ballet

© ASH

Founded in 1978 by the late Harold King (1949–2020), the London City Ballet (LCB) had enormous appeal and was staunchly supported by ballet lovers across the UK. It started with lunchtime shows at the Arts Theatre in London’s Leicester Square, and for almost twenty years became one of the most popular and successful touring companies, having regular seasons at major venues including Sadler’s Wells. Its reputation was enhanced when Diana, Princess of Wales, became the patron in 1983, doing a huge amount to raise the profile of the company and its dancers. She remained its patron until 1996 when financial problems forced the company to close.

The demise of the company was widely mourned, but Marney is about to change all that. He has had an illustrious dance, teaching and choreographic career. His varied experiences have seen him performing with Matthew Bourne’s New Adventures for many years, creating roles such as Count Lilac in Bourne’s Sleeping Beauty. He has also worked with the BalletBoyz (then George Piper Dances) as well as Michael Clark. He was artistic director of Central School of Ballet from 2016, and most recently director of the Joffrey Ballet Studio Company in Chicago.

London City Ballet outside Sadler's Wells in 1988

© Peter Teigen

I ask him why he decided to resurrect LCB. “It was the first company I saw”, he tells me. “It was in 1990 and I was eleven. My mum took me. We didn’t see the companies in London. We lived in Essex and we would see LCB at The Queen’s Theatre, Hornchurch, because that was the company that toured and would perform at your local theatre. That’s how I fell in love with it. It ignited my passion for ballet. It has always been in the back of my mind.”

I’m keen to know what his starting point was. “The first thing I did was to acquire the rights, which was relatively easy”, he says. “There were no assets. I wanted to make sure that I wasn’t disturbing the legacy. I was put in touch with Heather Knight [former administrative director to Harold King], who is truly amazing. She has been really instrumental in this process. She said, ‘You’ve got to do it because Harold was never precious, he would have loved to see it have a life’. She put me in touch with all the board members, who are all still alive and they agreed it would be wonderful – as long as I was up for taking it on a new journey, I should do it. That gave me the confidence to go and speak to Alistair Spalding at Sadler’s Wells.”

“I’ve probably known Alistair for 20 years but I don’t think we’ve ever had a proper conversation. I decided to just come out with it and told him bluntly. He sat bolt upright and said, ‘Are you really?’. He was completely supportive and said he remembered the company fondly from when he worked at The Hawth. He knew Heather well, he liked the ideas, doing new works, but also bringing works back that audiences haven’t seen, that people can’t go and see readily at other places. I don’t want to duplicate work that you could see on another stage. Alistair also said he would be happy to programme us for a week on the main stage next September.”

For Marney, understanding the history of the company itself has been important for its revival. “The University of Surrey hold the archives for London City Ballet and I’ve seen them. I met a wonderful guy called Paul Grace who was the company’s technical director, who is now the tech director at Birmingham Royal Ballet. He was the one in 1996 who had to fold the company and figure out what to do with all of it. All the boxes were at the national dance archives at the University. It was fascinating. Although there was a lot of uncategorised material that I couldn’t look at, they had a scrapbook of every year of the company’s existence, with newspaper clippings. I was able to piece together a history. It gave me an arc of how the company functioned, when they were doing great, and when they were not.

“They almost closed in 1991. They thought that everyone was going to have to sign on the dole, but they hung on until 1996. Then the board and chairman had fully expected the Arts Council to kick in, but they didn’t. They were running a company of 32 dancers and an orchestra. It was crippling.”

He continues, “It wasn’t like it is now where companies do a project and then have a few months off. Harold ran the company year round. He was constantly fundraising. Princess Diana would hold a yearly reception where they would raise £250,000 for the company. Paul told me that the closer you’d sit to Diana, the more expensive the seat would be. She would donate all this money for the next season of LCB. She was a huge help.”

Jane Sanig as Swanhilda with London City Ballet in Coppélia

© Peter Teigen

Marney has talked to a number of former LCB members. “It’s been so important for me to look back, before I plan forwards”, he says. “I’ve always loved the history of dance, and what’s come before. It’s been a very strong element of how I saw my career. I think it’s probably from Christopher Gable [former artistic director of Central School of Ballet], who was adamant that we had to know everything and see everything and appreciate what had happened before us. Yes, I want to take this in a new direction with a new generation but I absolutely respect what has come before.”

I’m interested to know if he ever worked directly with Harold King. He explains, “I first met Harold when I was graduating from Central School of Ballet. I trained there, did my MA there and then in 2016 became artistic director. I think this is why I always approach things as a performer, as a choreographer or programming an evening of work – I want to look back and see what I can draw upon, rather than only doing new things. Having had conversations with Deborah MacMillan, I’m planning to resurrect some repertoire that has fallen out of the rep with mainstream companies. I’m going to use it as a vehicle for bringing back all of these older, wonderful works, like Kenneth MacMillan’s Ballade, which have disappeared, not because they aren’t good enough but, like Ballade, which only has a cast of four, perhaps doesn’t fit with the larger companies. It’s a passion of mine but it’s also about not losing the important history of these works. There is a whole world of unexplored ballets.”

Kate Lyons, London City Ballet's rehearsal director, with Juan Gil

© ASH

I’m curious to know if he will be presenting his own choreography. “I know there are plenty of choreographers out there touring their work but I wanted to have a rep company”, Marney says. “In the past it might have been more common to tour rep companies but I don’t think it’s the trend anymore.”

LCB had previously had a relationship with Sadler’s Wells and I wonder if this will be reinstated. He reveals more exciting news: “It won’t be our home, no. It will be our performance home but we will have a purpose-built office and studio in Islington – unbelievably! We’ll have an office when we’re around, but we’ll be able to lease the studio when we’re not. It’s important to have a base. Creation of work needs to be in a really safe space.”

Marney plans to run the first three years on six month contracts, “So we will work from April to September/October, going to UK venues and also go to these lovely European festivals in the summer. I wanted to do a flexible programme and it looks like we will be going to Portugal. We do have some international dates in August. It's a good way of having a profile outside of the UK.”

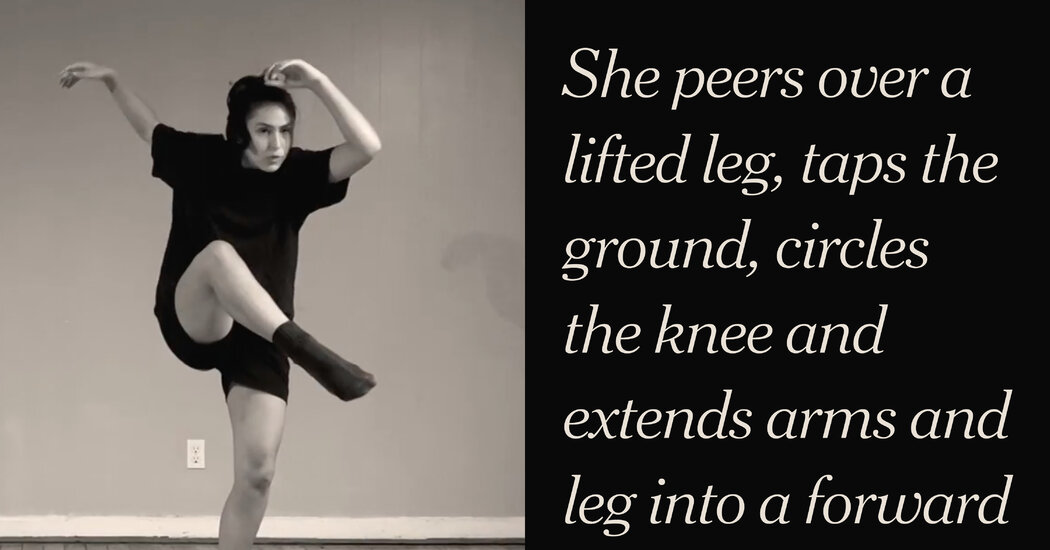

Ayça Anil, a dancer with the new London City Ballet

© ASH

The company will start with twelve dancers next year but Marney is keen to stress the need for flexibility. “For example, there is something I’m dying to do in one season and I only need seven dancers. I don’t want to put dancers out of work, but I want to make sure that I have dancers that are a perfect fit for the roles.”

The company will be supported by private subsidy and at present has enough support for three years. “Because I know that the first year is just donations,” he says, “any profit will go back into the company. It’s a good place to start. I reached out to some of the venues that had a history with LCB. The response was so heartening. We will open in Bath Theatre Royal in July. It will do well because there’s a demand for it. Dance companies are not coming to mid-scale venues any more, less since the pandemic and arts council cuts.”

As well as staging Ballade, Arielle Smith will create a new piece; they will have some exciting guest artists and he’s clearly got many more projects in the planning. A large proportion of the dance world are thrilled.