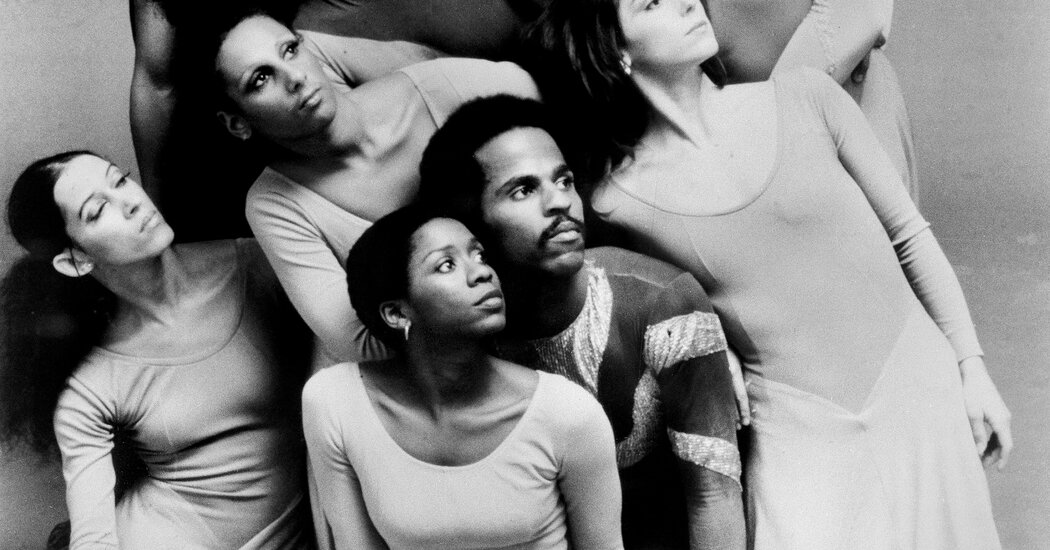

Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer and Arthur Harel.

(La)Horde

Madonna, Cronenberg, and Cannes Connect Dance Collective (La)Horde

[ad_1]

Pinging across eclectic points of reference, French collective (La)Horde channels hyperlink culture into dance.

One experiences their work as one would a fervid, late-night Wikipedia binge, making synaptic links as influences from David Cronenberg, Kim Kardashian, Gene Kelly, Will Wright and Ludwig Wittgenstein collide and collapse onstage. Offstage and in the crowd, influential fans and collaborators like Léa Seydoux and Spike Jonze take in repeat visits, with devotee Marion Cotillard well onto her fifth performance.

Cotillard needn’t travel far when she wants to see them again. Though co-founders Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer and Arthur Harel have brought shows to Los Angeles and New York in recent years, and have creative directors of choreography for Madonna’s ongoing Celebration Tour, they remain artistic directors of the Ballet National de Marseille – where they might stay, if they so choose, until 2029.

They are also very likely to turn up at next month’s Cannes Film Festival as part of the team for Gilles Lellouche’s “Beating Hearts” — an ambitious, decades-spanning romance expected to make a Croisette premiere.

Still, don’t expect the august perch to change (La)Horde’s approach. The collective’s three millennial artists share a generational view forged by 1990s video stores and 2000s Queer nightlife, and fed by a plugged-diet supercharged by social media.

“We always try to stay alert,” says co-founder Marine Brutti. “Whether you’re on social networks, in a movie theater, on the street or in the air, the world is always coming at you. So we try to monitor those sensations, and once something intrigues us, we get into the studio to unpack and understand.”

Age of Content

All of those threads entwined in (La)Horde’s most recent production created with Ballet National de Marseille, “Age of Content” – a playfully postmodern show that remixed Tik Tok dances with Old Timey musical numbers, while casting Juicy Couture clad dancers as video-game characters, programmed by an unseen hand.

“As a collective, we ask ourselves what are the issues facing us today,” says co-founder Arthur Harel. “And we try to answer by offering another perspective, a different way of looking at the world.”

“Video games and social media have opened new idea of the self, as bodies move through these virtual and digital spaces,” says Debrouwer. “Only if street dance is omnipresent on social networks, it’s also robbed of all history and political meaning by a format that requires movement at a ten-second clip.”

The three collaborators then connected this programmatic choreography to video game NPCs (non-playable characters) and to midcentury Broadway – where social malaise became spectacle.

“There’s any irony to ‘West Side Story,’ to watching a dozen people sing ‘America’ while crammed into a small room,” says Harel. “The audience doesn’t know if they’re smiling out of pleasure, out of duty, if they’re happy, or if they’re tired. There’s something cynical, and at the same time extremely pleasurable and performative about it – and we wanted to push those sliders all the way to the max, to make everything explode.”

The collective took evident delight in another irony as well: The fact that video game designers often looked towards dance to give virtual characters some heft.

“We had a lot of fun imagining how to imitate those who have tried to imitate us,” says Brutti. “What would happen when we reappropriated what digital characters took from human bodies? Would we mimic them, would we return to our original ways, or would [this copy-of-a-copy] leave an influence?”

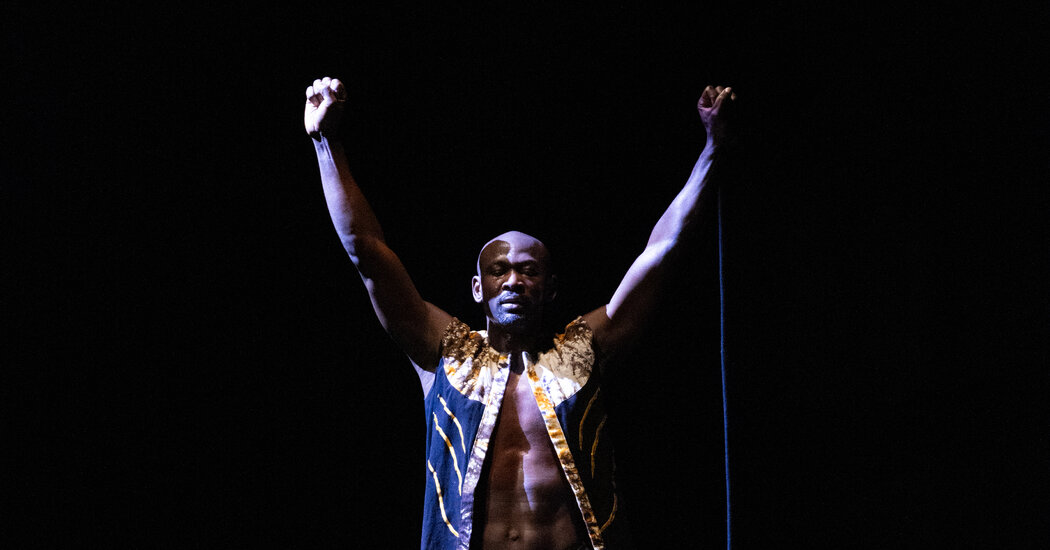

‘Age of Content’

Ballet national de Marseille

Celebration Tour

When envisioning new numbers for Madonna’s Celebration Tour, the trio drew influence from the singer’s own past. Of course, given the Material Girl’s five-decades on the pop charts, such a choice was often a product of necessity.

“Practically all of our sets had already been choreographed,” says Brutti. “So we were playing with this idea of a retrospective. Sometimes we had to refresh an older choreography, and sometimes we got to be a bit more meta, comparing the icon today against who she was at the time. And that was particularly moving.”

When asked to tackle, “Papa Don’t Preach,” for instance, the trio knew better than to one-up a previous version.

“We couldn’t compete with the number from the Blond Ambition tour,” says Harel. “So rather than running against it, we chose to run alongside. The original version had Madonna pleasuring herself in bed, so we put her back on the same bed – only now she wasn’t alone.”

The choreographers introduced a double – an image of the star from four decades before – and had the duo recreate the familiar routine as the present interacting with the past.

“She was rediscovering herself,” says Brutti. “Reclaiming her body.”

LONDON, ENGLAND – OCTOBER 14: (Exclusive Coverage) Madonna performs during opening night of The Celebration Tour at The O2 Arena on October 14, 2023 in London, England. (Photo by Kevin Mazur/WireImage for Live Nation)

WireImage for Live Nation

Collaboration is Key

Perhaps given the security (and responsibility) that comes with their perch in Marseille, the collective’s founders haven’t exactly chased after such international collaborations, though this play-it-cool approach has evidently added to (La)Horde’s luster.

In 2020, Spike Jonze first wrote a script for the trio to direct before sponsoring them to the join the roster at production outfit MJZ, while their “Unholy” video with Sam Smith and Kim Petras was born of a backstage encounter. They first spoke with Madonna over Instagram DMs – responding to a message that she sent.

“We never thought that one day we’ll be working for any pop star,” says Harel. “We chose this profession to be free, so the work has made sense [in that regard]. But when Madonna talked to us about her life and desire to work with us, it was hard to say no. She’s very persuasive!”

“We joke that next we’ll work with Rihanna,” says Brutti. “But that’s also not a wider goal.”

“Working as a collective ensures a constant exchange,” she continues. “Everything we do becomes highly intellectualized –necessarily so — because we first have to align before we can get into action. And then, once everything has been said, we head to the studio to be moved, to find moments of grace and of elevation that are beyond analysis, beyond words.”

“Once you’ve said everything there is to say about an idea, what else can you do but turn it into an emotion,” adds Debrouwer. “Dance is a universal language, so the dancers pick up where the conversation ends.”

‘Age of Content’

Fabian Hammerl

Cinematic Inspiration

Alongside various forms of new media, cinema remains a constant (and constantly renewing) source of inspiration.

“We’re always watching Cronenberg,” says Debrouwer.

“Nobody focuses on the body in quite the same way,” he continues. “He is often accused of subjecting the body to violence, but Cronenberg is the only director to avoid slow-motion when shooting a car crash. He depicts action at the speed at which it actually happens, without sublimating. You get the impression that it’s more violent, but that’s just because it’s more raw.”

More to the point, the trio sees wider parallels in their very creative practice — and are currently fielding various offers to make their feature directorial debut.

“We are directors,” Harel explains. “We’re really directing an overall vision rooted in a very specific [lexicon]. Obviously, choreography and dance are key to our work, but we’re not [austere and academic], staging the dance in the middle of nowhere, in the dark. We need a set, we need lighting, we need costumes, and we need a context.”

‘Age of Content’

Fabian Hammerl

Cannes Then and Now

Keeping with that cinematic verve, the trio recently orchestrated four musical sequences in Gilles Lellouche’s “Beating Hearts” – coming up with showstoppers and set-pieces performed by Adèle Exarchopoulos and François Civil, among others.

The most ambitious French production of the year, “Beating Hearts” is hotly tipped for Cannes.

But then, Cannes’ Palais des Festivals is already familiar ground for (La)Horde, who ran rampant inside and outside the familiar site for their 2022 performance “We Should Have Never Walked On The Moon” — a line Gene Kelly once told Buzz Aldrin at a Hollywood dinner party.

“Intellectually, politically, and physically, Gene Kelly felt that walking on the moon was a form of vandalism,” says Brutti. “And to know that one of the greatest of all dancers – one of the most elegant stars of all time – felt such passion really kickstarted our imagination.”

(La) Horde channeled that outrage into a raucous piece that mixed Cannes Film Festival iconography with visions of civic unrest, leaving the famous red carpet smoldering. Should the troupe return to the Croisette in May, they’ll have to find a more genteel expression for their showmanship – and are keen to take up the challenge.

“We can’t dare to be as punk in more formal situations,” adds Brutti with a laugh. “But why not? We could pull something off – can you imagine?!”

‘We Should Have Never Walked On The Moon’

Théo Giacometti

[ad_2]

Source link