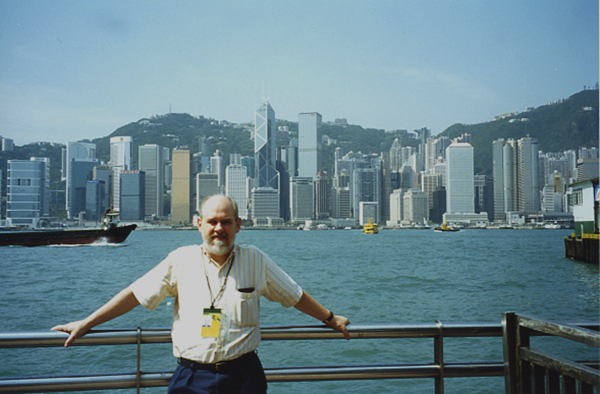

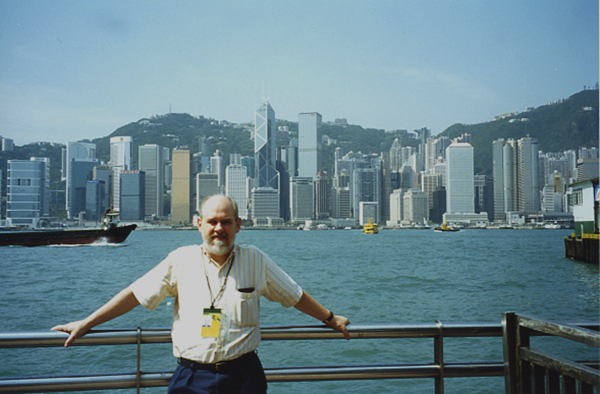

David shopping during his first trip to Hong Kong, 1995

Kristin here:

By now many of you have watched the recording of David’s May 18th memorial service, linked in the previous entry. Some have written to tell me how moving it was and how many aspects of David’s personal life and career the speakers covered. Absent, however, was one of the greatest loves of his professional life: his many visits to Hong Kong and his book on that city’s cinema were represented only by a video recording of his acceptance of an Asian Film Award in 2007. It was a lovely moment, but no one who could present personal recollections of David’s Hong Kong connection was among the speakers.

Now, however, Li Cheuk-to, David’s close friend throughout his days in Hong Kong and our visits to Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, has written a piece that paints a vivid picture of David’s visits to Hong Kong. It conveys his deep enthusiasm for a national cinema that had largely been dismissed by critics and scholars in the West. The piece was posted online in Chinese on March 28, and Ah To, as we knew him, has kindly agreed to having the English version posted here.

Going back through the blog, I have found and linked entries written by David and describing some of the events that Ah To mentions below.

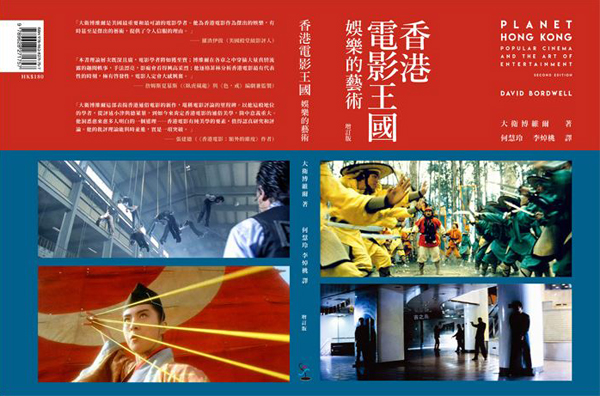

Planet Hong Kong

David in his element, 2000

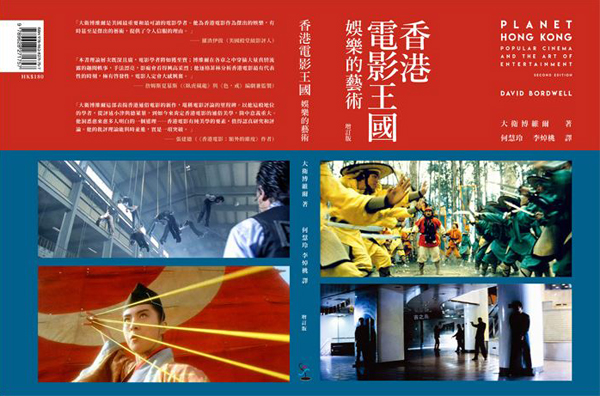

David Bordwell passed away at the end of February, and the global mourning voices far exceeded the reaction to the death of any other film scholar. This proves that his wide circle of friends and profound influence go beyond the identity of a university professor. Apart from colleagues and students in academia, more responses came from friends he met at film festivals around the world, filmmakers, and fans who interacted with him through the blog “Observations on Film Art.” But what we feel most intimately connected to is his book Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, in which he celebrated Hong Kong cinema as a self-sufficient industrial system outside Hollywood, possessing its own unique aesthetics. While he also introduced films from many countries around the world in Film History: An Introduction, the only national cinemas he wrote individual books on were American and Hong Kong cinema.

Bordwell’s works are generally more enjoyable than most academic writings. They are remarkably well-written, free of pedantry, and often sprinkled with witty humor. What’s rare is that he isn’t deliberately trying to be accessible; rather, he enthusiastically shares his insights with readers with an open mind, without any hint of the condescending attitude that many scholars inevitably adopt. In this respect, he is as easy-going as his writings; we all enjoy conversing with him because he never makes you feel inferior. He is also a willing listener who is open to different opinions, making it easy to achieve fruitful two-way communication. Expert on Chinese cinema Shelly Kraicer believes that he perfectly embodies the democratic spirit of American scholars and the tradition of trusting students’ intelligence, in contrast to the elitism of the European academia. I can’t agree more.

A fanboy’s first trip to Hong Kong

Planet Hong Kong as one of Bordwell’s most popular works stands out in these aspects, but it is by no means a coincidence. Because he openly admits that he has been an otaku (geek, nerd, or enthusiast) since childhood, discovering Hong Kong cinema through the kung fu films of the 1970s (Five Fingers of Death, Jeong Chang-hwa, 1972, and Fist of Fury, Lo Wei, 1972), just like many Western fans of Hong Kong movies. He even screened some of them in his classes. Unsatisfied with the usual channels like cinemas and film journals, he subscribed to fan magazines and collected videotapes and laserdiscs to update his knowledge of Hong Kong films. Therefore, he embodies a dual identity of a small fan and a distinguished professor, yet he neither falls into the fanaticism of a fanboy nor keeps a distance with the subject of study like most scholars. Instead, he maintains a clear-headed, heartfelt love for these films.

In 1995, his first visit to Hong Kong to attend the Hong Kong International Film Festival became a pivotal turning point. It was not only the centenary of cinema, but more importantly, the festival’s programme that year broadened his horizons. The new friends he made there made him feel at home, and he fell deeply in love with the city of Hong Kong: This will always be the place!

He wrote about the awe he felt sitting in the front row of the Hong Kong Cultural Centre’s Grand Theatre watching Abbas Kiarostami’s Under the Olive Trees. He also had the chance to see the newly unearthed Love and Duty with Ruan Lingyu (Bu Wancang, 1931), as well as new prints of The Orphan, starring the young Bruce Lee (Lee Sun-fung, 1960) and The Eight Hundred Heroes (Ying Yunwei, 1938). The festival that year opened with In the Heat of the Sun (Jiang Wen, 1994) and Summer Snow (Ann Hui, 1995). He could rewatch his beloved Chungking Express (Wong Kar Wai, 1994) and catch up on Hong Kong gems from the same year like He’s a Woman, She’s a Man (Peter Ho-Sun Chan, 1994), The Private Eye Blues (Eddie Fong, 1994), The Final Option (Gordon Chan, 1994), and The New Legend of Shaolin (Wong Jing and Corey Yuen, 1994). (Below, David and Peter Ho-Sun Chan.)

During that year, he also attended the presentation ceremonies of the Hong Kong Film Critics Society Awards and the Hong Kong Film Awards, where he met his admired stars and directors such as Wong Kar Wai, Ann Hui, and Tsui Hark, feeling ecstatic like a fanboy. (Above, David presents the Best Director award from the Hong Kong Film Critics Society for Ashes of Time.) However, more importantly, through the friends he made at the film festival and his experiences walking the streets and marveling at the architecture of Hong Kong, he truly felt the vibrant energy, fast pace, and visual stimulation of Hong Kong cinema, realizing its inseparable connection to the place and its people.

He admitted to becoming addicted to visiting Hong Kong from that point on, continuously attending the film festival in March and April for seventeen years without interruption. In 1997, he wrote an article titled “Aesthetics in Action: Kung Fu, Gunplay, and Cinematic Expressivity” for the Hong Kong cinema retrospective catalogue Fifty Years of Electric Shadows. The following year, he wrote “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” for the retrospective catalogue Transcending the Times: King Hu and Eileen Chang. In retrospect, these two articles were early drafts of what would later become Planet Hong Kong. The former used Lethal Weapon and A Hearty Response (Norman Law Man, 1986) as examples to illustrate the stylistic differences in handling action scenes between Hong Kong films and Hollywood, which he also presented during a three-day symposium at the film festival, where the audience erupted into thunderous applause after the screening of the car chase scenes from the two films – what a memorable moment!

In fact, in the two to three years around the time of the handover in 1997, every time he visited Hong Kong, he met with many Hong Kong filmmakers in preparation for his book Planet Hong Kong. One unforgettable memory was a late-night gathering at the end of 1997 with members of the Hong Kong Film Critics Society, where they talked until the early morning and even went karaoke together! Keeto Lam and Bryan Chang still remember that he sang “All Kinds of Everything” and “Losing My Religion.” During that time, we agreed to have the translated version of the book edited by me on behalf of the HK Film Critics Society. After he completed the first draft the following year, he sent me a copy for review. The scene of staying late at the office and discussing the content with him over a two-hour long-distance call is still vivid in my memory today.

A fixture in Hong Kong film culture

Seated, left to right, Shelley Kraicer, Athena Tsui, David, Erika Young, Nat Olson,

and standing, Ann Gavaghan, Tim Youngs, and Li Cheuk-to

Planet Hong Kong was published in 2000 (and in translation by Ho Wai-leng, Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Critics Society, 2001) , and there was not enough time to write about Johnnie To in his Milkyway Image period in the book. However, when he was invited to be a visiting professor at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts in 2001, he visited the set of Running Out of Time 2 (2001) and the two hit it off immediately. Since then, every time David visited Hong Kong, Director To extended his hospitality, and in the second edition of the book in 2010, David filled this gap and resolved any regrets. (Below, from the left, standing Lau Ching-wan, Shan Ding, and Johnnie To; sitting, Ekin Cheng Yee-kin, David, and Kristin)

During this decade, the most special moment was in 2007 when he was awarded for “Excellence in Scholarship in Asian Cinema” at the inaugural Asian Film Awards, with Johnnie To as the presenter. Just like when he first visited Hong Kong, he took photos of and collected autographs from the surrounding stars and directors. Before the awards ceremony, in addition to discussing the content of the citation with Grady Hendrix, I also had Bryan Chang create a short complementary video featuring a stack of a dozen books that David had given me.

[Note: The online recording of David’s memorial service includes the presentation of the award, including Bryan Chang’s brief film. KT]

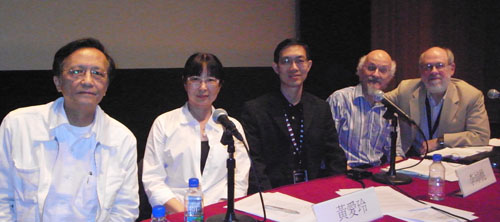

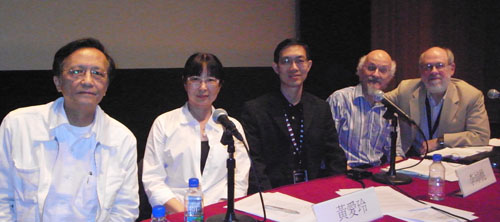

Two years later, he was invited to speak at a panel discussion on “The Controversial Centenary of Hong Kong Cinema” at the film festival, along with Law Kar, Frank Bren, and Wong Ain-ling, where they weighed the evidence for and against Stealing the Roast Duck (Leung Siu-po, 1909) and Zhuang Zi Tests His Wife (Lai Park-Hoi and Lai Man-Wai, 1914) as the first film made in Hong Kong.

Law Kar, Wong Ain-ling, Li Cheuk-to, Frank Bren, and David

However, what excited him the most at that edition of the film festival was probably the “A Tribute to Romantic Visions” retrospective celebrating the 25th anniversary of Film Workshop (co-founded by Tsui Hark and Nansun Shi), featuring screenings, exhibition, publication, lectures, and parties, creating a star-studded and bustling atmosphere. Additionally, the successful restoration and resurfacing of Fei Mu’s lost work Confucius (1940) was also a great pleasant surprise for him.

A fanboy’s last trip to Hong Kong

Unfortunately, around the same period, when he came to Hong Kong to attend the film festival, he experienced respiratory issues perhaps due to the air pollution in Hong Kong, often coughing uncontrollably. Athena Tsui remembers accompanying him to a private hospital for a late-night visit (to avoid disrupting the next day’s work), where they even summoned a radiographer in the middle of the night to take X-rays for him, and he quickly received the results, indicating no immediate danger. After returning to his home country, he showed the report to his own doctor, who greatly praised the professionalism, efficiency, and expertise of the Hong Kong medical staff, once again leaving him in awe.

Due to this chronic lung condition, he heeded the doctor’s advice not to come to Hong Kong for two years. In 2014, he accepted an invitation to join the jury for Young Cinema Competition at the film festival (other jury members included Bong Joon-ho, Karena Lam, and Christopher Lambert, above), marking his final visit to Hong Kong. Nevertheless, being able to see the director’s black-and-white version of Mother and engage in deep discussions with Bong Joon-ho could be considered as leaving a good memory, right? In the following years, the only occasion where he would meet with me annually was at the Il Cinema Ritrovato Festival in Bologna, Italy at the end of June, where he always appeared alongside his wife, Kristin Thompson.

Kristin is also a renowned film scholar who co-authored two classic film textbooks with David, and their blog was co-written, as we all know. However, she is also an Egyptologist who conducts research in Egypt once a year, like David’s annual visits to Hong Kong. Over the years, she accompanied her husband to the film festival in Hong Kong once in 2000. Athena Tsui remembers their fondness for desserts from The Sweet Dynasty, such as walnut and almond soup.

David particularly enjoyed mango pudding and was a regular customer at Hui Lau Shan. Before the closure of KPS Video Express, he would always buy many Hong Kong movie laserdiscs whenever he visited Hong Kong.

[Note: Many of these laserdiscs are now in David’s and my collection in the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. KT]

In recent years, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we naturally missed the chance to meet again. Last September, I had planned to visit him in Wisconsin, Madison after attending the Toronto International Film Festival. Unfortunately, his health deteriorated, requiring hospitalization, and we missed seeing each other once again. Occasionally, we would receive emails from Kristin updating us on his condition. Eventually, we received the sad news of his passing. It was reassuring to know that in his final days, they would watch a movie together every night, and on the last night, they rewatched two episodes of The West Wing. For those who truly care, this was a comforting end.

Lastly, it must be noted that six years ago when we decided to publish the translated version of the second edition of Planet Hong Kong (with the new material translated by Li Cheuk-to, aided by a few friends), he promptly wrote a new postscript for it without hesitation, for which we are truly grateful. Looking back today, when we sent him the printed translated version four years ago, he was still well amid the pandemic. Undoubtedly he was delighted to see that he finally completed a full circle with his connection to Hong Kong cinema. At the time, this Chinese version was meant to commemorate Wai-leng. Today, as David has passed away, I realize that this can also be seen as showing our utmost gratitude and respect to him.

The second edition of Planet Hong Kong is available for free here. There is still a notice about not copying the book for others, but that is left over from the days when David was selling his digital books online. The page where the book is available also has David’s description of how he came to love Hong Kong cinema, visited Hong Kong for the festival, and wrote the book.

The blog entries on Hong Kong that I have linked here are only a few of the many he posted. The rest can be found by clicking on the “National Cinemas: Hong Kong” link in the menu at the right.

Li Cheuk-to, photographed by David in 2000

Last Modified: Wednesday | July 17, 2024 @ 15:15  open printable version

open printable version

This entry was posted

on Sunday | June 30, 2024 at 3:27 pm and is filed under National cinemas: Hong Kong, PLANET HONG KONG: backstories and sidestories.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.