The Maltese Falcon (1941).

DB here:

The traditional opposition between Art and Entertainment still holds some sway. Art, some believe, is the realm of higher significance and profound emotion, while entertainment yields mere diversion and superficial engagement. Art embodies wisdom and technical breakthroughs, while at best entertainment is home to talent and cleverness. Art harbors genius, entertainment offers ingenuity. Art expresses the creator’s personal vision, entertainment recycles collective fantasy (or the Zeitgeist). There’s usually an implied hierarchy of quality and of appeal: art is for a sensitive elite, entertainment is popular (read vulgar).

One problem, though, is that for long stretches of history much art has been thoroughly entertaining. Mozart, Shakespeare, Dickens, Hiroshige, Austen, and many other major artists have found wide popularity. They provide pleasure aplenty. But with urbanization and the rise of capitalism, mass production created a huge public, and tastemakers have tended to treat art as a realm apart. For a hundred years or more, entertainment has been equated with mass culture, and art with high culture, most notably with modernism and its successors.

Another problem is cultural endurance. In a recent column, Michael Dirda points out that genre fiction often outlasts prestigious literary fiction of its era.

Take fantasy and science fiction: In 1997, I praised William Gibson’s “Neuromancer,” John Crowley’s “Little, Big,” Gene Wolfe’s “Book of the New Sun” and the works of Ursula K. Le Guin — all remain vital to contemporary writers and readers.

Similarly, classics of mystery fiction by Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, and Patricia Highsmith still attract readers, while “mainstream” novels of their eras are forgotten. Dirda’s second point is no less valid.

More generally, American novelists have wholly embraced the energy and potential of fantasy in its various forms. We are all fabulists now. This century revels in comics, graphic novels, manga and superhero movies. Authors as varied as Colson Whitehead, Walter Mosley, Kelly Link, Jonathan Lethem, Elizabeth Hand and Michael Chabon, to name a few prominent figures, all grew up loving fantasy and science fiction.

Genre appeals have infiltrated prestige literature, as in the crime plots of Graham Greene, Joyce Carol Oates, and Richard Price. (I consider Colson Whitehead’s and Richard Wright’s contributions here.) Likewise, we have horror-infused tales like George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo and Lorrie Moore’s I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home .

Creators of entertainment have felt the distinction keenly. “A wedge has been driven into the industry,” says Christopher MacQuarrie, director of the latest Mission: Impossible installment. “Are you an artist or an entertainer? Tom doesn’t see them as mutually exclusive.” But some creators have seen a forking path. Rex Stout, after several “serious” novels failed, came to two conclusions:

First—that I was a good storyteller, and second—that I would never be a great novelist. I’d never be a Tolstoy, or a Dickens, or a Balzac…. So since that wasn’t going to happen, to hell with sweating out another twenty novels when I’d have a lot of fun telling stories which I could do well and make some money on it.

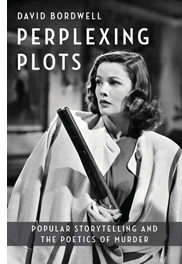

The Art/ Entertainment distinction runs through my recent book, Perplexing Plots, because many mystery writers have aimed at “elevating” their work to the level of prestige literature. This urge drives them to experiment with the norms of plotting and writing. Even when the genre limits remain in force, there’s a chance that skillful exponents can accept them and still yield “literary” pleasures. A good example is what happened to hard-boiled detective fiction in the hands of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler.

The Op

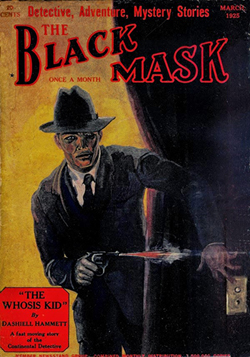

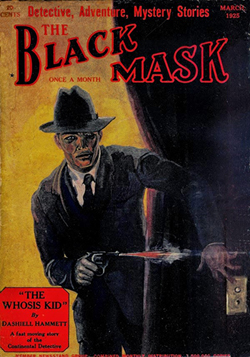

Hammett launched his fame with a series of crime stories mostly published in the pulp magazine Black Mask from 1923 to 1930. His protagonist is a nameless investigator for the Continental Detective Agency. The Continental Op, as he came to be called, is a pudgy but tough middle-aged detective who values camaraderie, crafty stratagems, and a good cheap steak. Women flirt with him, but he sees through their schemes. The Op’s drabness and humility give him a realism that is amplified by the milieu Hammett depicts. He had been a Pinkerton agent and larded the stories with underworld argot and tips on investigative technique.

Hammett launched his fame with a series of crime stories mostly published in the pulp magazine Black Mask from 1923 to 1930. His protagonist is a nameless investigator for the Continental Detective Agency. The Continental Op, as he came to be called, is a pudgy but tough middle-aged detective who values camaraderie, crafty stratagems, and a good cheap steak. Women flirt with him, but he sees through their schemes. The Op’s drabness and humility give him a realism that is amplified by the milieu Hammett depicts. He had been a Pinkerton agent and larded the stories with underworld argot and tips on investigative technique.

Black Mask stories put a premium on action, so the Op was often at the center of violence perpetrated by crooks, sociopaths, and corrupt cops. Unlike other hard-boiled detectives, the Op isn’t a swaggering sadist. Violence is his last resort; he favors obstinate everyday professionalism. Sometimes he’s fooled by the grifters and has to wriggle his way out. At other times, he can set crooks against one another and watch the mutual destruction.

Hammett wrote the stories in the first person, giving the Op a telegraphic, visceral style laced with sour humor. A 1923 story shows his American vernacular already in place.

Just at the wrong minute Henderson decided to look over his shoulder at us–an unevenness in the road twisted his wheels–his machine swayed–skidded–went over on its side. Almost immediately, from the heart of the tangle, came a flash and a bullet moaned past my ear. Another. And then, while I was still hunting for something to shoot at in the pile of junk we were drawing down upon, McClump’s ancient and battered revolver roared in my other ear.

Henderson was dead when we got to him–McClump’s bullet had taken him over one eye.

McClump spoke to me over the body.

“I ain’t an inquisitive sort of fellow, but I hope you don’t mind telling me why I shot this lad.” (“Arson Plus”)

In 1929, the publisher Knopf issued two Hammett novels, Red Harvest and The Dain Curse, based on Black Mask serials. The Op had not lost his wit or his gift for staccato narration. Here are three excerpts.

I didn’t think he was funny, though he may have been.

He stood at the foot of the bed and looked at me with solemn eyes. I sat on the bed and looked at him with whatever kind of eyes I had at the time. We did this for nearly three minutes.

The latch clicked. I plunged in with the door.

Across the street a dozen guns emptied themselves. Glass shot from door and windows tinkled around us.

Somebody tripped me. Fear gave me three brains and half a dozen eyes. I was in a tough spot. Noonan had slipped me a pretty dose. These birds couldn’t help thinking I was playing his game.

I tumbled down, twisting around to face the door. My gun was in my hand by the time I hit the floor.

Across the street, burly Nick had stepped out of a doorway to pump slugs at us with both hands. I steadied my gun-arm on the floor. Nick’s body showed over the front sight. I squeezed the gun. Nick stopped shooting. He crossed his guns on his chest and went down in a pile on the sidewalk.

Hands on my ankles dragged me back. The floor scraped pieces off my chin. The door slammed shut. Some comedian said:

“Uh-huh, people don’t like you.”

As he was finishing The Dain Curse, Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf confessing that in future work he wanted to go beyond Entertainment to Art.

I’m one of the few—if there are any more—people moderately literate who take the detective story seriously. I don’t mean that I necessarily take my own or anybody else’s seriously—but the detective story as a form. Some day somebody’s going to make “literature” of it (Ford’s Good Soldier wouldn’t have needed much altering to have been a detective story), and I’m selfish enough to have my hopes, however slight the evident justification may be.

The question is: How to do this?

Inside and outside

Hammett proposed an answer in his letter to Blanche Knopf. He wanted to try that he wanted to try out modernist technique in a third novel.

I want to try adapting the stream-of-consciousness method, conveniently modified, to the detective story, carrying the reader along with the detective, showing him everything as it is found, giving him the detective’s conclusions as they are reached, letting the solution break on both of them together. I don’t know whether I’ve made that very clear, but it’s something altogether different from the method employed in “Poisonville [Red Harvest],” for instance, where, though the reader goes along with the detective, he seldom sees deeper into the detective’s mind than dialogue and action let him.

His mention of stream of consciousness may mislead us about his intentions. In that technique the verbal narration seeks to mimic the flow of the mind as it flits across sensory impressions, memories, and fantasies. The process is often rendered as sentence fragments, often introduced by a sentence indicating the behavior of the character.

Here’s an example from Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), the most famous showcase of stream of consciousness. Mr. Bloom is in a Catholic church.

He saw the priest stow the communion cup away, well in, and kneel an instant before it, showing a large grey bootsole from under the lace affair he had on. Suppose he lost the pin of his. He wouldn’t know what to do to. Bald spot behind. Letters on his back I.N.R.I? No: I.H.S. Molly told me one time I asked her. I have sinned: or no: I have suffered, it is. And the other one? Iron nails ran in.

Sometimes the images and phrases are separated by commas and periods, but sometimes they simply pile up. In the book’s last chapter, Molly Bloom’s drowsy imaginings are given in an unpunctuated, sparsely paragraphed flow.

It’s likely that Hammett didn’t want his usage to be as fragmentary as what we encounter in Joyce and others. His invocation of Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier (1915) suggests something closer to what many now call inner monologue. (Ford called it “impressionism.”) Here the flow of thought is given as a sort of soliloquy, a flow of more or less cogent and coherent ideas and impressions. What makes it a modernist technique is that inner monologue may not respect story chronology and it’s likely to be biased, uncertain, equivocal, and subject to revision. Ford’s narrator, John Dowell, tells a rambling, out-of-order tale of marital infidelity and suicide, in which flashbacks are analyzed and re-analyzed.

Looking over what I have written, I see that I have unintentionally misled you when I said that Florence was never out of my sight. Yet that was the impression that I really had until just now. When I come to think of it she was out of my sight most of the time.

At the climax, Dowell makes a provisional sense of what the characters knew and why they acted as they did.

The problem in importing this to the detective story is evident. How can the detective’s ongoing reasoning, bristling with mistaken inferences and reconstructed impressions, be passed along to the reader without causing confusion? For this reason, detective story narration, whether first-person or third-person, suppresses most of the protagonist’s reasoning. The Watson figure and the dumb authorities exist to be baffled and play with misleading possibilities while the detective holds back even a partial solution.

By convention, the climax of the tale is the revelation of the truth–not when the detective discerns it, but at the moment when it can be announced with decisive impact (often in a gathering of suspects with the police present). Raymond Chandler noted that the delayed revelation was a serious constraint of the genre, even when the detective, like the Op, is telling the story. “The first person story is assumed to tell all but it doesn’t. There is always a point at which the hero stops taking the reader into his confidence.” The detective “stops thinking out loud and ever so gently closes the door of his mind in the reader’s face.” This prevents the public announcement of the solution from being anticlimactic.

Worse, Ford’s protagonist Dowell is an unreliable narrator, as the above passage suggests. To make the detective’s first-person account unreliable would be more than a “convenient modification” of the standard plot schema. It would push toward the experiments seen in Cameron McCabe’s The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor (1937) and later “anti-mysteries.”

Hammett admitted in a later letter that he would put the “stream-of-consciousness” experiment on hold while he wrote material for Hollywood in “more objective and filmable forms.” (That would include his script for City Streets of 1931, which does include a subjective auditory flashback rare in films of the time.) But in his next novels Hammett turned sharply away from the interiority he had considered. Instead, he went toward extreme objectivity, almost completely shutting us out from his protagonists’ inner lives.

The action of The Maltese Falcon (1930) and The Glass Key (1930) attach us closely to his protagonist, scene by scene. We’re confined to his activity and his range of knowledge. But this doesn’t get us into his mind. For these books Hammett switched to third-person narration and made it radically objective, sticking almost completely to reporting dialogue and character interaction.

In Perplexing Plots, I explore how this strategy works, but here’s an example from The Glass Key.

At Madison Avenue a green taxicab, turning against the light, ran full tilt into Ned Beaumont’s maroon one, driving it over against a car that was parked by the curb, hurling him into a corner in a shower of broken glass.

He pulled himself upright and climbed out into the gathering crowd. He was not hurt, he said. He answered a policeman’s question. He found the hat that did not quite fit him and put it on his head. He had his bags transferred to another taxicab, gave the hotel’s name to the second driver, and huddled back in a corner, white-faced and shivering, while the ride lasted.

The narration presents what a third-person observer would have seen and heard, and it won’t venture into Beaumont’s thinking. The cues are behavioral: he seems cool enough in slipping out of the crash, but his true reaction is given through his nervous reaction while riding back to the hotel.

As Hammett’s second letter to Blanche Knopf suggests, this flat objectivity would seem an ideal novelistic basis for a “filmable” treatment. John Huston’s screen adaptation of The Maltese Falcon confines us almost completely to Spade’s range of knowledge. (The big exception is that we see his partner Miles Archer shot by an unknown killer.) The film’s visual narration mostly follows Hammett’s impassive neutrality. But when Casper Gutman drugs Spade, we get Spade’s clouded optical viewpoint.

In the novel the narration reports that Spade’s eyes seemed to muddy over. When he says, “And the maximum?” we’re told that “An unmistakable sh followed the x in maximum as he said it.” This isn’t Spade’s experience but rather what an observer would register, an “unmistakable” impression confirmed when we’re told that “a sharp frightened gleam awoke in his eyes.” As Spade tries to walk, he’s tripped by Wilmer. He falls and Wilmer kicks him. “Once more he tried to get up, could not, and went to sleep.” The whole scene is rendered externally.

So instead of giving the detective story a modernist subjectivity, Hammett went to the other extreme. Did he intuitively recognize the problem of revealing the detective’s inferences too soon? Maybe, although his increasing involvement with Hollywood may have kept him on the objective, “filmable” path. The Thin Man (1934), his last novel, is a fascinating effort to return to first-person narration while incorporating the dry objectivity of the two previous books.

Perhaps inadvertently, Hammett’s radicalization of the objective method yielded what he had hoped for. The Maltese Falcon was greeted as a serious work of literature and was soon incorporated into the prestigious Modern Library series. His works have become part of the canon of American letters enshrined in the Library of America collection. The convention of delaying the detective’s solution didn’t prevent the genre from becoming accepted as a legitimate literary form–at least as practiced by Hammett, and his most prominent successor.

Overtones, echoes, images

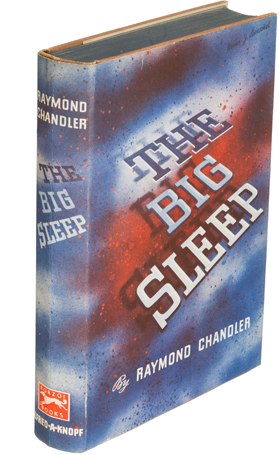

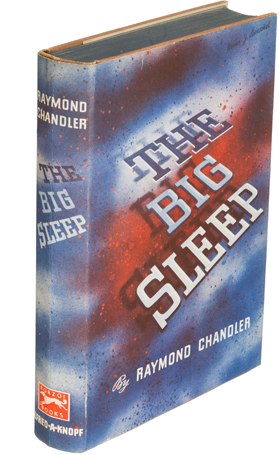

That successor was, of course, Raymond Chandler. Ten years after Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf with his hopes of elevating the whodunit, Chandler wrote to Alfred Knopf about his plans for The Big Sleep (1939) and the novels that followed. It has an echo of Hammett: “I was more intrigued by a situation where the mystery is solved by the exposition and understanding of a single character, always well in evidence, rather than by the slow and sometimes long-winded concatenation of circumstances.”

That successor was, of course, Raymond Chandler. Ten years after Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf with his hopes of elevating the whodunit, Chandler wrote to Alfred Knopf about his plans for The Big Sleep (1939) and the novels that followed. It has an echo of Hammett: “I was more intrigued by a situation where the mystery is solved by the exposition and understanding of a single character, always well in evidence, rather than by the slow and sometimes long-winded concatenation of circumstances.”

But what Chandler means by “understanding” doesn’t include full-blown reasoning. First-person narration, he explains in a 1949 note, must “suppress the detective’s ratiocination while giving a clear account of his words and acts and many of his emotional reactions.” This seems a response to the detached reportage of late Hammett prose. Chandler also rejects the Op’s streetwise patter by explaining to Knopf that his method will use “a very vivid and pungent style, but not slangy or overtly vernacular.” He wants “to acquire delicacy without losing power.”

Hammett, while a voracious reader, learned a good deal of his craft from actually investigating crimes. Chandler, who began writing mysteries as Hammett’s productivity tailed off, owed his knowledge of the mystery genre to reading. He studied crime fiction of all sorts with almost academic passion and became one of the most nuanced commentators on the tradition. He claimed to have learned plotting from outlining pulp stories by Erle Stanley Gardner. His literary tastes didn’t run to modernism. He admired the Greek and Roman classics, Flaubert, James, and Conrad and thought highly of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Hammett imagined elevating the genre by “conveniently modifying” modernist technique, but Chandler sought to make the hard-boiled detective story more like the ambitious mainstream novel.

He believed he could do that through style. In his crucial essay, “The Simple Art of Murder (1944/1946),” he praises Hammett’s prose but objects that “it had no overtones, left no echo, evoked no image beyond a distant hill.” Chandler sought to give style a greater novelistic richness not only through probing his protagonist’s mind but also through fairly dense descriptions colored by the protagonist’s emotions and judgments.

Hammett sketches characters in quick strokes and he merely indicates settings. But Chandler dwells on his characters and their surroundings. The opening of The Big Sleep devotes a page and a half to Philip Marlowe’s impressions of the Sternwood mansion (stained-glass window of a knight rescuing a lady, plush chairs, a mysterious portrait) and another page and a half to his meeting with the coy Carmen. These are filtered through Marlowe’s running commentary. The knight doesn’t really seem to be trying. The chairs appear to never have been sat in. The portrait looks threatening. Carmen’s infantile flirtation reveals that “thinking was always going to be a bother to her.” Here are the overtones and echoes that Chandler finds lacking in Hammett. This is an ominous household–as Marlowe will later say, this will be “no game for knights.”

Chandler would pursue this method in the following novels. Yet at times the narration plunged deeper into subjectivity. In Farewell, My Lovely (1940) Marlowe is repeatedly knocked out in tussles, and in the second passage Chandler writes:

The man in the back seat made a sudden flashing movement that I sensed rather than saw. A pool of darkness opened at my feet and was far, far deeper than the blackest night.

I dived into it. It had no bottom.

The film adaptation, titled Murder, My Sweet (1944), uses this subjective device in every knockdown. Marlowe’s voice-over narration runs through the film, and after the first assault we hear:

I caught the blackjack right behind my ear. A black pool opened up at my feet. I dived in. It had no bottom.

Onscreen we see Marlowe’s crumpled body blotted out by a miasma that leads to a black frame.

In a later sequence, a knockout of Marlowe is rendered as wild optical exaggerations before following the novel’s report of Marlowe seeing a room full of smoke. That’s translated as wispy superimpositions over the shots, with explanatory voice-over.

The film tries a bit too hard, but its use of voice-over and delirious visual subjectivity would become common in film noirs of the period.

In Farewell, My Lovely, Marlowe’s recovery from his first knockout is rendered with vigorous subjectivity across two pages, as Marlowe realizes that the voice he hears reviewing what happened is his own. “I was talking to myself, coming out of it. I was trying to figure the thing out subconsciously.”

Marlowe is able to reconstruct bits of the crime through this process, but it’s a provisional solution, not the decisive one. That one he keeps from the reader until the climax. By then, as per convention, the door to his mind has shut in the reader’s face.

Hammett’s novels were published when most crime fiction consisted of genteel whodunits and gangster sagas, so he had the advantage of novelty. By the time Chandler published The Big Sleep, he was competing with many book-length stories of hard-boiled investigators. Aware of the need to establish a distinctive presence, he presented work that stood apart by its social criticism and the romanticized realism of a righteous avenger alone on the mean streets of a corrupt city–sure-fire attractions to intellectuals then and since. Just as important was his self-consciously literary style. “In the long run, however little you talk or even think about it, the most durable thing in writing is style, and style is the most valuable investment a writer can make with his time.”

Through concern with language’s echoes and overtones, he established himself as Hammett’s successor. The literati followed his lead and declared him a significant novelist. His books, along with “The Simple Art of Murder,” provided an enduring rationale for the tough detective story. While adhering to the conventions of the classic puzzle (clues, faked deaths, false identities, least-likely culprit), he acquired lasting prominence. Like Hammett he has found a home in the Library of America.

Arguably Hammett and Chandler also elevated their genre. Their achievements encouraged other ambitious writers and stimulated critics and readers to look more closely at the possibilities of the murder novel. No wonder that prestigious writers have turned to mystery plots. Fans still labor to make a case for Golden Age puzzles as art rather than entertainment, but most critics and readers assume the hard-boiled mystery to be at least potentially serious literature–especially when it goes under the alias “noir.”

Nowadays the Art/ Entertainment duality has weakened its hold. If, as Dirda suggests, we are all fabulists now, we’re also probably mystery fans to some degree. It’s likely that film played a role here, in showing intellectuals that films by Hitchcock, Ozu, and other popular directors were of high quality. More and more, I think, people aren’t as eager to see the split as absolute. Instead of a hierarchy, we have more of a spectrum.

In harmony with this, Perplexing Plots argues that culture offers us a plenitude of individual works with varied appeals, all of which can be realized with, to use Chandler’s terms, delicacy and power. Some works rely on subtlety, others on immediate impact. We have the refinements of Baroque music and the direct force of The Rite of Spring. If Treasure Island is a masterpiece a well as a rousing yarn, so is Die Hard. There is heavy art and light art, brooding art and and diverting art, intellectual density and emotional charm. None of these qualities is simple or easy to achieve; all can repay analysis. The slogan might be: “There’s valuable work at all levels. And there are no levels.”

One source of value, not always acknowledged, is the role of entertainment in revealing fresh expressive possibilities in the medium. For example, the martial arts cinemas of Japan and Hong Kong opened up new vistas of cinema. And yes, as Hammett and Chandler indicated, a lot of the freshness lies in style. This is why Perplexing Plots spends time looking closely at how mystery fiction and film work, word by word or shot by shot. Even Agatha Christie’s supposedly bland verbal texture points up ways in which language can mislead us.

So Hammett and Chandler didn’t “elevate” the hard-boiled story so much as blur the line between genre fiction and the “legitimate” novel. Ambler and Le Carré did the same for the spy story, as did Highsmith for the psychological thriller. For such reasons, Perplexing Plots discusses hard-boiled detection extensively. I explore the Art/ Entertainment distinction because it has obsessed critics and creators. But I try not to buy into the split, opting instead for the looser idea of “crossover.” It’s a swap meet, with storytellers ransacking works “high” and “low” for subjects, forms, techniques, whatever.

I wanted to put up this entry on 23 July, Raymond Chandler’s birthday. It happens to be mine too. No cheerleading here, though. I prefer Hammett, as maybe you can tell.

My quotations from Hammett’s letters come from Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett, 1921-1960, ed. Richard Layman and Julie Rivett (2002). I take Chandler’s remarks on mystery fiction from Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler, ed. Frank MacShane (1981) and Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. Dorothy Gardiner and Katherine Sorley Walker (1962).

Michael Dirda, as my mentions of him should lead you to expect, has written an admirable example of taking popular storytelling seriously but not solemnly: On Conan Doyle, or the Whole Art of Storytelling (2014). Kristin does something similar in her Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes, or Le Mot Juste (1992), available here and here. Her immensely popular subject, P. G. Wodehouse, was regarded as a master of English prose by Martin Amis, Evelyn Waugh, and many other literary celebrities.

What about the third celebrated hard-boiled pioneer, Ross Macdonald? Read Perplexing Plots to find out!

Murder My Sweet (1944).

Last Modified: Sunday | July 23, 2023 @ 09:07  open printable version

open printable version

This entry was posted

on Sunday | July 23, 2023 at 9:07 am and is filed under 1940s Hollywood, Film and other media, Narrative strategies, PERPLEXING PLOTS (the book).

Both comments and pings are currently closed.