Babylon (2023).

DB here:

The circus parade has just passed, and behind it comes a little man mopping up all the droppings left by the lions, tigers, camels, and elephants. Somebody calls out, “Why don’t you quit that lousy job?”

The little man answers: “Are you kidding? And leave show business?”

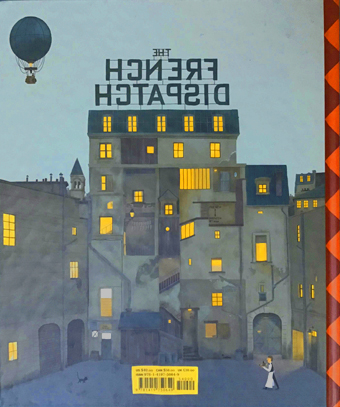

From one angle, the joke anticipates the dramatic arc of Babylon. Damien Chazelle’s film traces how five characters seeking a future in the movies immerse themselves in a debauched culture, all for the sake of the dream machine.

For trumpeter Sidney Palmer and singer/actor Fay Zhu, the movie moguls’ bacchanals pay the bills and allow networking. Jack Conrad, a major star, loves being a drunken libertine but expresses contempt for the films he makes, movies that are only “pieces of shit” rather than innovative high art. Manuel Torres becomes an all-purpose gofer on set and eventually a studio executive, trying to work within the system. Nellie LaRoy is attracted to the movie world as much for the whirl of drink, drugs, dance, gambling, and fornication as for the glamor drenching the screen. Finding her film persona as the Wild Child, she can act by acting out.

These characters, all from working class origins, are brought together at a moment of technological upheaval: the period 1926-1934, with the establishment of talking pictures. This would seem to threaten moviemaking, not to mention the high life offscreen. Other pressures include the stock market collapse and the resulting depression, along with the establishment of a stricter standard of what could be depicted onscreen, the famous Hays Code. (The Code isn’t mentioned directly in Babylon, but it’s suggested as part of a broader concern with morality in the film colony.)

By the time sound has fully arrived, all of Babylon‘s primary characters, voluntarily or not, are no longer working in the Hollywood industry. Fay Zhu leaves for European production. Sidney, whose band is ideal for sound cinema, quits in disgust after he’s forced to darken his skin further. When the press and the public turn against Jack, he commits suicide. Nellie dances off into darkness and a lonely death. Manny, vainly in love with Nellie, can’t halt her self-destruction and has to flee town to avoid reprisals from the mob. From this angle, a confluence of debauchery and technology has wrecked whatever spark of life the system had.

The bleak satire that is Babylon poses a host of questions. Why, for instance, are there apparently deliberate anachronisms? The backdrop sets for the Vitoscope’s outdoor filming would be unlikely for 1926. Jack misquotes Gone with the Wind a decade before the book was published. The vast opening orgy seems more typical of Von Stroheim’s films than any actual Hollywood party on record. And given Vitoscope’s marginal status, how does the studio head afford such a mansion?

But I’m interested today in the ways the characters seek fame. I think their situations are a development of qualities we’ve seen in other Chazelle show-biz films. One way or another, nearly all those characters have sought to find a creative impulse that can make the compromise with a corrupt system yield some artistic rewards. The pressures and temptations of Babylon are extreme versions of factors we’ve seen at work in Whiplash and La La Land, but the characters react rather differently.

The suicidal drive for perfection

Whiplash (2014).

I think about that day

I left him at a Greyhound station

West of Santa Fé

We were seventeen, but he was sweet and it was true

Still I did what I had to do

‘Cause I just knew. . . .

These are the first lines we hear at the start of La La Land. Sung by a young woman slipping out of her car, they foreshadow the film’s plot developments. Sebastian and Mia, the couple at the center, both put their careers ahead of their love for each other and separate at the end. Each seeks success–Mia in screen acting, Sebastian in starting a jazz club–and that drive blocks a compromise in which one or both might give up their dreams for the sake of staying together.

Chazelle’s first two show-biz films present artistic achievement as a solitary quest that demands you to surrender normal ties to others. His strivers are loners, unable to subordinate their “dreams” to the demands of mutual love. Sacrificing everything to their quest, they have the self-righteous egocentrism of Romantic poets.

Whiplash tells the story of Andrew Neiman, an aspiring jazz drummer in music school. Worshipping Buddy Rich, he wants to be “one of the greats” himself. He spends hours in grueling solitary practice, and he has no friends. He is distant from his family, except for his father, with whom he goes to movies as if he were still a kid. He gives up a beginning romance with a young woman because, he tells her, he needs the time to practice.

The film introduces Andrew alone, bent over the drum kit, a distant figure in a corridor. In what follows, Chazelle isolates him, not through overwrought long shots showing him as remote from other students, but en passant, by medium shots that let us glimpse them in normal hallway conversation behind him.

Apart from competing with his peers, Andrew runs into Terence Fletcher, the fearsome leader of the school’s top jazz ensemble. Fletcher finds him practicing, invites him to try out for the band, and proceeds to run him through a program of brutal aggression, laced with just enough encouragement to keep Andrew on the hook. Good father/ bad father: the dynamic seems primal, but it’s an unequal struggle. Fletcher, always clad in satanic hipster black, knows how to dangle the prospect of success in front of Andrew’s bleary eyes.

That success comes in some degree, but haltingly. Andrew rises in the ranks, but through a series of unlucky mishaps, he humiliates himself in a major competition and assaults Fletcher onstage. He’s kicked out of school, but he’s also pressed to testify about his teacher’s abuse. It remains for Fletcher to entice Andrew one more time, tricking him into another public fiasco. Yet Andrew turns it into a sort of triumph.

Fletcher bullies Andrew into saying, “I’m here for a reason.” That reason, to put it in highfalutin terms, is the prospect of excellence within a worthy artistic tradition. To become as good as Buddy Rich is a wonderful prospect. But that’s a rosy picture. Breaking with Nicole, Andrew displays some of Fletcher’s cold-bloodedness, leading her to ask in her parting line, “What the fuck’s wrong with you?” She’s referring to his chopping off human ties, but she might as well be stressing Whiplash‘s suggestion that with that purity comes an eager masochism that is heightened by the master’s sadism. To be an artist is to sacrifice normal human ties but also to submit to a punishing game of power.

That game is played out in the career of Andrew’s idol. Buddy Rich, a technical virtuoso, had a combative view of musicianship. He conducted celebrated duels with other drummers and was said to have believed that for him, the drum was the solo instrument and the orchestra merely a batch of accompanists. As a bandleader, he was famous for vituperative attacks on his players. At once an obsessive like Andrew and a tyrant like Fletcher, he personifies the performer as a solitary seeker after inhuman perfection.

In what appears to be a burst of sincerity, Fletcher tells Andrew that the abuse he inflicts is solely to push the player to go beyond what’s expected. Only that will create the next Charlie Parker. Learning of the suicide of a student he tormented, he seems genuinely shaken–although he lies to his players by saying the boy died in a traffic accident. The sheer aggression that darkens his quest for quality is revealed when he deliberately sabotages his ensemble’s performance to make Andrew flub the piece.

At this point, though, Andrew catches some of Fletcher’s fury by launching into a maniacal solo. In its frenzied drive, it seems as if it could go on forever. By sheer force he wrests control of the orchestra from Fletcher, who seems with a smile to recognize what has happened and eventually plays along. He guides Andrew in a Rich-like descent into slower, then faster tempo. Reconciled with the strict father and the whiplashes he’s received, Andrew has demonstrated his heedless devotion to an exceptionally severe jazz tradition.

Music and machine

La La Land (2016).

Before it enacts the lovers’ separation foreshadowed in the opening song, La La Land gives us two protagonists aspiring to show-business success. Mia runs around town auditioning for TV shows, while Sebastian nurtures the dream of opening a jazz club. Like Andrew in Whiplash, Mia’s a loner with no deep relation with her peers. Sebastian, also a loner, harbors a conception of jazz playing that’s as combative as Buddy Rich’s. He explains a performance not as a communal exchange but as rivalry.

Look at the sax player right now. He just hijacked the song. He’s on his own trip. Every one of these guys is composing, they’re rearranging, they’re writing, and they’re playing the melody. And now the trumpet player, he’s got his own idea. And so it’s conflict and it’s compromise. . .

The game can get deadly. “Sidney Bechet shot somebody because they told him he played a wrong note.”

What drives the young and hopeful? The opening song suggests two impulses. First, there’s the fantasy realm of movies. “A Technicolor world made out of music and machine/ It called me to be on that screen/ And live inside each scene.” Second, there’s an urge to show the people back home that you’ve made it. “‘Cause maybe in that sleepy town/ He’ll sit one day, the lights are down/ He’ll see my face and think of how he/ used to know me.”

But neither purpose seems to be primary for Seb and Mia. True, Seb is a movie fan who quotes James Dean, but the couple aren’t apparently driven by fantasy. And although Mia comes from the sticks, she isn’t vindictive about it. Instead, they worry about succumbing to the mediocrity of the world they want to enter.

Jazz is dying, Sebastian laments. He plays at a piano bar and can’t introduce his own playlist. He picks up work as a keyboardist in an uninspiring but successful progressive-R&B ensemble. Mia auditions for clichéd roles and is facing a life as a barista.

The emptiness of their milieu is encapsulated in two party scenes. Unlike the infectious party in Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench (2009), these are scenes of careerist networking. Parties, Mia’s roommates argue, are essential for advancement; the person you schmooze today could hire you tomorrow (“Someone in the Crowd”). At the first party, confronted by snobs, Mia flees to the bathroom to confront herself in a mirror: Who is she really going to be? When she comes out, the party has become a sterile erotic tableau.

The alternative to giving people what they want is giving them you. Because Sebastian has found something of himself in jazz, he urges Mia to express herself in a one-woman show. She has her own tradition–the Hollywood movies her aunt showed her, and which she mimicked in skits she mounted as a girl. The show earns her an audition, where she channels her own experience in a song monologue about her aunt’s Paris adventures (“The Fools Who Dream”). It’s something of a reply to her mirror scene at the party. She gets the part, a lead to be built around her as a character.

Her successs and Sebastian’s steady if uninspiring life on tour initiate their breakup. Neither will sacrifice a career for a life together. Jazz may be conflict and compromise, but the only compromise visible here comes in the alternative time-frame climax showing the couple sharing domestic happiness. Somehow Mia has found stardom, with Seb as supportive spouse. But that’s a hypothetical outcome. As in Whiplash, you can achieve excellence by commitment to a personal tradition, but at the cost of close ties to others.

Party like it’s 1926

In the show-biz musicals, Chazelle’s protagonists’ goals aren’t defined as specific achievements–not winning a drumming prize but somehow becoming a drumming great, not getting a part in a particular show but getting some part in any show. Accordingly, like many off-Hollywood efforts, the films have episodic plot structures. Scenes tend to be more or less self-contained, with few dangling causes to lead to the next. Deadlines are set within a series of end-stopped scenes, not for the film as a whole. The action may be driven by coincidence, accident, and happenstance.

The episodic quality is less evident in Whiplash, whose scenes are dictated by scheduled rehearsals, solitary practice, and concert dates. Even there a flat tire, followed by a car crash, adds to the dramatic tension, and coincidence reintroduces Andrew to Fletcher after both have left the school. La La Land gives us a cascade of meet-cutes before the couple finally goes on a date. After that, their career trajectories depend chiefly on fortunate job offers, but also on Seb’s failing to remember a photo shoot. At the climax, a coincidental moment of traffic gridlock brings her and her beefcake husband back to the club to encounter Sebastian and the prospect of the future that might have been.

Moving from one protagonist to two to several in Babylon, Chazelle’s episodic inclination poses new problems. The major characters aren’t intimately connected, as in many network narratives. Manny is in love with Nellie, but he rarely sees her, and then only by accident. All are linked by being in the Hollywood system, and for the most part Chazelle is obliged to rely on crosscutting to interweave their developing careers.

The technique synchronizes their trajectories. Nellie is hired as actor at the first party, while Manny becomes Jack’s aide by escorting him home. The next day, as Nellie finds surprise success in her role for Vitoscope, Manny saves MGM’s costume picture by fetching a camera in time for a magic-hour shot. (The roots of Hollywood: a last-minute rescue.) Nellie’s rise to second lead is paralleled to Jack’s success in Blood and Gold, while Manny becomes Jack’s trusted assistant, sent to New York to catch the premiere of The Jazz Singer.

As the industry tries to assimilate sound, Nellie struggles and MGM hires Manny to supervise its Spanish-language production and coordinate musical shorts with Sidney’s band. Jack’s films start to bomb, Nellie’s star image goes out of style, and Manny rejoins Kinoscope to rehabilitate her. She remains a wild child, however, and Jack starts to realize his career is ending.

The storylines come to bleak endings when Jack commits suicide and Nellie drags Manny into her downward spiral, making them targets of James McKay’s mob. Once separated, Nellie vanishes and Manny flees the business. Sidney returns to playing live jazz for Black audiences, and his solo accompanies a montage sequence launched by Jack’s funeral and including a news story about Nellie’s 1938 death, possibly of a drug overdose.

To bring these protagonists physically together, Babylon relies chiefly on parties–five, by my count. The first and most sumptuous is an orgy hosted by Kinoscope’s boss Don Wallach. It demonstrates the dissipation of Hollywood culture. How could the comparative purity of Andrew or Mia or Sebastian survive this plunge into the mire? If nothing convinces one of the need to stand apart from the Hollywood milieu, this explosion of decadence should do it. Manny is a fixer (the guy sweeping up after the parade). Jack samples the fruits–a drink here, a quick copulation there–but Nellie is utterly in her element. She becomes the life of the party. If hedonism is an index of stardom, she shows, as she says, she was a star the moment she walked in.

At the party, Nellie and Manny explain why they’re attracted to this milieu. Manny says he wants to be part of something bigger, and he loves movies because they let you live the characters’ lives. Nellie agrees. Later, after she’s hired, she’ll holler that this will show everybody who said she was a loser. The two rationales–immersive fantasy and surprising the folks back home–are the same ones given in the opening song of La La Land. They have nothing to do with artistry in a tradition.

Jack’s case is a little different. He defends film as a high art, claiming that it needs a shot of modernism akin to Bauhaus design or twelve-tone music. Yet he has so little respect for his art that he plays his roles in an alcoholic stupor and condemns most films as shit. And claiming that sound would be as revolutionary as perspective in painting seems sheer silliness, especially after his joyless role in a regimented rendition of “Singin’ in the Rain.” In his longest tirade, he drops back to a mass-popularity argument. He tells his current wife that his immigrant parents found meaning in the nickelodeon, and millions more people will see him than will visit an O’Neill play.

You can argue that, like Mia in La La Land, Nellie and Jack succeed through self-expression. Nellie can cry on command because she remembers home; Jack cuts a dashing figure by his very nature. But they don’t work at their craft, or discipline their self-expression. Offscreen Nellie is a wastrel and Jack is a drunken pseud, babbling Italian, playing opera records, and garbling highbrow debates about mass culture and high art. Natural vitality gives Nellie and Jack some currency in the turmoil of silent film, but the discipline of talkies renders them obsolete.

They’re bereft of a tradition, though Jack senses the need for one. By contrast, Sidney has not only the jazz tradition but also, surprisingly, Scriabin. (Though in the Fletcher vein he admires Scriabin’s mutilation of his hands to play virtuoso passages.) It’s Sidney who quits the business out of principle. Not incidentally, he and Lady Fay seem the only protagonists with a powerful talents.

The second party, also hosted by Wallach, is somewhat more sedate than the first, though Nellie can be glimpsed nuzzling a unicorn’s horn. This initiates a montage that culminates in Nellie ecstatically watching her screen performance with an audience, who assail her for autographs.

The third party announces “Hooray for Sound” and brings together the three major characters in a night of frenzied activity. It’s reminiscent of the opening bacchanal, but seems more desperate, driving Nellie to break more bounds by daring death from a rattlesnake. (Lady Fay is the only partygoer bold enough to rescue her.) When Jack sees the melée that results, an uncharacteristically sustained and sober close-up, scored to a doleful piano, suggests that he senses that his milieu is headed for self-destruction.

Next party, far more upscale: Nellie tries to display her rehabilitation at a luncheon at a millionaire’s mansion. But her clumsy efforts to be genteel are mocked and so she lets loose with obscenity, attacks on food, and aggressive vomiting. Jack, Manny, Sidney, and FeiZhu have assimilated, but Nellie reverts to being the raucous low-life from Jersey. It’s career suicide. In parallel sequences we see Sidney forced into blackface and Jack frozen out by MGM.

The fifth party is a nightmarish descent into purgatory. “LA’s last real party,” McKay says as he ushers Manny and his colleague into a labyrinth of degenerate spectacle. Echoes such as the song “Her Girl’s Pussy” reveal the initial orgy as naive devilry: here is real shock. It’s as if the denizens of Hollywood have had their nerves rubbed so raw that only the most sadistic and gruesome entertainment will satisfy. Has this party been going all these years?

Taken all in all, it seems to me that the party sequences make explicit what the La La Land parties only suggested: to succumb to this milieu is fatal. The solitary quest of these lost souls render them vulnerable to temptations that will ruin them. In the Biblical Babylon, by pursuing false gods, the feasters have been weighed in the balance and found wanting. This is the story of people who think the party life (on the set of off) can last forever.

Granted, unlike Mia and Sebastian, the protagonists of Babylon have no other paths to their art. In the studio system, old-timers have assured us, you had to socialize with the decision-makers if you were to have a career. There were no equivalents of niche music clubs or indie film producers. In an odd way, Babylon is a roundabout tribute to the fluid artworld of today.

But then there’s the much-discussed final sequence.

Movies are bigger than ever

It’s 1952. Manny and his wife and daughter are visiting Los Angeles from New York, where Manny has a radio repair shop. As his wife and daughter return to their hotel, Manny drifts from the still-existent Kinoscope studio to a theatre. He finds himself in an audience watching Singin’ in the Rain. He sits transfixed, but his viewing is interrupted by a montage sequence that is, to say the least, a challenge to us.

What if the montage weren’t there? We’d have a scene in which Manny watches the new MGM movie restage the problems of early sound he witnessed, the tyranny of the mike and camera booth. He weeps. But then comes Kelly’s “Singin’ in the Rain,” which revises the mechanical chorus of old. Manny smiles. In his lifetime, the naive clumsiness of sound has been transmuted into something smooth and beautiful.

No wonder at the very end Manny is transported. He has achieved his hope of becoming part of something big. He has contributed to perfecting that imaginary world onscreen. We’d have what William Dean Howells claimed was the story all Americans wanted, “a tragedy with a happy ending.”

Hollywood has long justified its existence by appeal to magic. Disney provides the Magic Kingdom, while Lucas labeled his high-tech wizardry Industrial Light and Magic. At intervals throughout Babylon, characters echo the cliché. Jack calls a movie set the most magical place on earth; after his career has plummeted, he recalls the silent era in the same terms. The gossip columnist Elinor St. John celebrates “the camera’s magic tricks” in filming a battle. Without the inserted montage, Babylon‘s finale would confirm this mysterious magic, the way junk (the movies we see being made) can somehow become something splendid.

But we have that montage. Although it harbors many implications, it has the effect of sabotaging an upbeat ending. After a few shots recalling earlier scenes in the film (ending with the cliché of the couple passionately kissing), there’s a fusillade of images. They are snipped from silent cinema, abstract films, animation, widescreen splendors, foreign-language films, avant-garde films, computer films, CGI images, and wholly digital creations. Significantly, there are no Hollywood films represented from the 1930-1938 years we see in the last stretch of Babylon. It’s as if the visual narration is reminding us that the “something bigger” is indeed bigger than anything Manny experienced.

From one angle, it’s also a chronicle of technological change, all the “revolutions” that would follow the coming of sound. But where’s the magic? The usual counter to the mystique of magic is to point out the hard work of filmmaking. What delights us, on that account, is proficiency in craft and ingenious mastery of a tradition.

Chazelle floats another possibility. Having presented the digital future, he gives us luxurious images of dyes being mixed in colorful arabesques. Black-and-white footage is plunged into the brew.

What emerges are tinted versions of paradigmatic shots of the film we’ve seen: Nellie dancing on the bar, Jack on the promontory above the battlefield. Among more shots of the dyes mingling we see Sidney and Fay Zhu, now also tinted. The scenes we’ve seen have become part of silent film.

Bursts of pure color, interrupted by glimpses of live-action, close the montage.

The image is dissolved back into its most basic ingredients. A movie that started with a spray of elephant shit ends with streaks of translucent liquid sinuously circling one another. Movie magic, it seems, is a kind of alchemy, a distillation of molecular mixing within the hardware of filming, processing, and projection.

It’s tempting to take Elinor’s bleak consolation of Jack as the movie’s point: Long after he’s gone, future audiences will see him as a friend, at once an angel and a ghost. Perhaps the medium redeems anything it touches, lifting Nellie’s antics and Jack’s swagger to a luminous life everlasting. But this prospect negates the artistic premises of the two earlier films. Without a guiding passion to succeed through achievement, and with only an ebullient personality (Nellie) and some masculine grace (Jack) and a dutiful resourcefulness (Manny), have-nots can succeed in show business. For a while. When the parade is over, what’s left are spectral traces of its passing.

I have to say that decadent frescos like Babylon aren’t usually to my taste. I don’t much care for La Dolce Vita, Satyricon, The Damned, and comparable spectacles of luscious degradation. They have a moralistic, not to say moralizing tenor. But, as I tried to show here, liking or disliking a movie on grounds of taste doesn’t make the film uninteresting. A film can gain interest in the light of questions we can ask about its form, style, and themes (including political ones). On these grounds, the films by Fellini and Visconti remain important parts of the history of film, regardless of whether I find them sensationalistic. Similarly, while Babylon isn’t my favorite Chazelle film, I can appreciate its virtuosity, as in the frenzied crosscutting of the two 1926 shoots. I can also find its thematic inversion of his earlier work worth thinking about.

I don’t know what Chazelle the person thinks about artistic ambition and self-sacrifice. I do think that he has found a narrative model of the process that allows him to ask questions about whether creation is private or communal, self-expression or commitment to a tradition, ascetic denial or plunge into sensory distraction and self-exploitation. Most films never raise such questions.

On Buddy Rich’s style and career, I learned a lot from Jonathan Godsall’s article “Whiplash, Buddy Rich, and Visual Virtuosity in Drumkit Performance,” Twentieth-Century Music 19, 2 (2022), 283-309. Godsall is also good on how Chazelle’s cutting enhances Andrew’s performance.

Marya E. Gates offers a wide-ranging account of Babylon‘s references to silent-era filmmakers in this piece in Indiewire.

A helpful summary of the image-capsule montage at the film’s end is offered by Anthony Olesziewicz in Collider. Initially the sequence might seem to be Manny’s flashback, but the opening glimpses of his life in LA are quickly followed by examples ranging across film history, including years since 1952, which suggest a narrational commentary, like a footnote.

There are entries on other Chazelle films on this blog: La La Land (here and here) and First Man (here).

Babylon (2023).

Last Modified: Sunday | May 21, 2023 @ 11:50  open printable version

open printable version

This entry was posted

on Sunday | May 21, 2023 at 11:50 am and is filed under Directors: Chazelle, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, Hollywood: The business.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.