Observations on film art : Older, but wiser?

[ad_1]

Calais Pier (J. M. W. Turner, 1803).

Kristin here–

Over the past three years, starting early in the pandemic, I have found a soothing and edifying occupation which one can indulge in at home: doing online jigsaw puzzles. Mostly I choose ones with images of ancient Egyptian places and artifacts and of my favorite painters. Having exhausted the available Botticelli, Bruegel, Bosch, Van Eyck, and others, I decided to try J. M. W. Turner, whose work I was somewhat interested in. Doing puzzles, I realized, was a way of concentrating on their details, almost a form of analysis. I became quite fascinated, not to say obsessed, with Turner’s work. I’ve been reading a lot about him as well, since he’s a compelling figure for many reasons.

One of these is that about two thirds of the way through his long career his style began to change radically. He gained a reputation early on for detailed, realistic landscapes and seascapes such as, to give it its full title, Calais Pier, with French Poissards preparing for Sea: an English Packet arriving (he was fond of long titles). It was exhibited at the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition in 1803, when Turner was twenty-eight years old. His first oil painting to be in the exhibition had been Fishermen at Sea, seven years earlier (1796), and he had exhibited watercolors starting in 1790, when he was 15. Soon he was gaining fame and came to be considered by most as the greatest English painter. For decades his paintings commanded higher prices than those of his contemporaries, and he attracted a number of wealthy patrons who collected his work. He became the richest artist in Britain (a fact glossed over in Mike Leigh’s 2014 film, Mr. Turner).

During the 1830s and especially the 1840s, Turner’s style became less detailed and more abstract, emphasizing color and light rather than the subject, as in Approach to Venice, below, exhibited at the RA in 1844. He was 69 years old. He lived until 1851, dying at 76, and exhibited paintings of this sort until the year before his death.

This change caused many admirers and collectors to revise their opinions of the artist. Had his aged hands become unable to hold a brush steadily? Was his eyesight going? Was he more than a little touched in the head? Or had old age endowed him with some sort of visionary insight, as his most loyal supporters argued? “Late Turner” became a matter of controversy, with changing attitudes toward his challenging style continuing until the present. In the past few decades, one book and two exhibition catalogues have tackled the subject: the Salander-O’Reilly Galleries catalogue, Exploring Late Turner (1999),the Tate Britain catalogue, Late Turner: Painting Set Free (2014), and Sam Smiles’s The Late Works of J. M. W. Turner: The Artist and his Critics (2020).

This controversy reminded me of discussions that sometimes crop up among film fans and scholars. Are the late works of a given filmmaker greater than those what came before? Does age confer wisdom or philosophical resignation or a fear of mortality or some other kind of new understanding that is reflected in artworks in a stylistic or thematic fashion, creating a distinctive late period? I believe we do tend to believe this of artists, including filmmakers (primarily directors). Most audiences would probably think a retrospective of the later films of Yasujiro Ozu, say, from Late Spring (1949) on, to be as logical–maybe more so–than a series of highlights drawn from the surviving films of his entire career. The same might be true of Agnès Varda or Ingmar Bergman or other much-admired filmmakers with long working lives.

Let’s return to the career of Turner to see if there might be problems behind this assumption.

The Old Man and the seascape

Turner was well aware that he was a great painter, perhaps the best the UK had ever produced and quite possibly would ever produce. He was concerned that future generations should be kept aware of that. In 1848, three years before his death, he sought to guarantee that his legacy would last by revising the last of a series of wills, leaving all the finished paintings still in his home studio/gallery to the nation, on condition that a section in the National Gallery be given over to his work. Upon his death, his relatives contested the will, seeing these valuable objects slipping away while they were left with paltry sums of money.

After a five-year court case, the sage and fortunate judgment (fortunate for us, at least) was that it was impossible to tell which of the paintings were finished, so that everything in the gallery should be part of the bequest. This meant that hundreds of finished and unfinished oil paintings and tens of thousands of finished watercolors, unfinished watercolors, about 300 sketchbooks, casual sketches, studies, doodles, annotated train schedules (handy for following his many sketching travels), and paint equipment and supplies went to the nation. Most of the Turner Bequest, including abut 60% of his entire body of (finished?) oil paintings, is now in the Tate Britain, apart from several in the National Gallery. Most of the finished (?) watercolors are there as well.

At the time, as more and more of these paintings, finished or not, were cleaned, framed, and exhibited, for decades new Turners appeared before the public–almost as if he had never died. This included, of course, some of his older finished paintings that he had failed to sell or had deliberately held back or even bought back to represent his art to future generations. One such was that favorite of the British people, The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last berth to be broken up, 1838 (1839), for which he had refused a fabulous offer of five thousand guineas, more than ten times the usual price of oils by prominent painters of the day. He was 64 at the time. In that same year’s exhibition at the Royal Academy, Turner presented Ancient Rome: Agrippina Landing with the Ashes of Germanicus (see bottom). These two finished paintings demonstrate that Turner had not lost his physical or mental ability to paint very well indeed. Both were part of the Turner Bequest to the nation. (We know which paintings were finished and given titles by Turner largely if he exhibited them at the RA or in his own gallery, or if he sold them.)

Turner’s plan has succeeded spectacularly, and admiration for the artist quickly revived and has remained high ever since. (Since April of last year, his youthful self-portrait and part of The Fighting Temeraire have occupied the verso of the English twenty-pound note.)

The creation of a gallery devoted to his work, however, was slow to be accomplished. It took the formation of the National Gallery of British Art in 1897, later the Tate Gallery, now Tate Britain, plus the building of a new wing onto Tate Britain, finally accomplished in 1987 when the Clore Galleries extension was opened; it displays the large number of oils in rotation. Some oils and watercolors from the Bequest are now in the National Gallery and the British Museum.

When French Impressionism became an international sensation later in the century, some patriotic British art historians and critics pointed out that Turner had been a forerunner of the style. The claims gradually grew, with Turner touted as having used many of the Impressionists’ techniques years before they did. Ultimately some critics went completely overboard and declared that Turner had done everything the Impressionists did. The French were not amused, but the idea has lingered on.

Similar claims were made well into the twentieth century. Turner had invented Impressionism, then abstract art, then Expressionism, and then Abstract Expressionism. These claims were based partly on his finished later work, but also on the huge number of undated, untitled, and unfinished pieces like the one above. (It was not named by Turner, who didn’t expect anyone else ever to see it, but is called by the Tate Sea and Sky and also called Rain Clouds, estimated date 1845). Often removed from sketchbooks to be sold as individual paintings, the most preliminary of sketches ended up much later being shown in exhibitions simply as artworks, taken out of their original contexts. From generation to generation, he could remain “Turner, our contemporary.” How had he envisioned all these modern techniques? Presumably because of the deep understanding of a genius reaching old age.

All this culminated in 1966 when the Museum of Modern Art put on an exhibition, “Turner: Imagination and Reality,” mainly based on unfinished works. The paintings were taken out of their elaborate carved and gilded wood frames, put in new, simple ones, and hung in austere galleries. The exhibition was a huge success. When one of the curators was asked why a museum dedicated to modern art would present an exhibition centered on a painter who had been dead for over a century, he responded, “Because we know a modern painter when we see one.”

Since the 1980s the pendulum has gradually swung the other way. Thorough historical research on the artist’s context by Turner scholars has revealed him as an artist not of the twentieth-century world but of the modern world of his own day. He reacted to the Industrial Revolution with enthusiasm, integrating factories, trains, steamships, and other innovations into his works, mostly famously Rain, Steam and Speed (in 1844, when he was 69), a depiction of a train racing toward the foreground. As a painter primarily of landscapes and seascapes, he was fascinated by all aspects of the natural world and had many friends who were making the major scientific discoveries of the age in a wide variety of fields, including Michael Faraday and Mary Somerville.

Most of his “abstract” sketches and studies, like the one above, were attempts to capture the movements of clouds, storms, waves, and any number of other natural phenomena, often based on his knowledge of the revelations of scientists. Presumably they served as reference images for potential use as details in future paintings. The obsession he developed with pure color did not arise from an elderly man’s poor eyesight or an uncanny prediction of artistic trends to come. All his adult life he voraciously read theoretical treatises on painting, and the 1840 translation into English of Goethe’s Theory of Colours had a profound influence on him. His own copy, annotated with both approving and argumentative comments, survives. John Constable, both Turner’s rival and his friend, commented that he had “a wonderful range of mind.”

Smiles’s book The Late Works of J. M. W. Turner, mentioned above, is entirely devoted to tracing the claims about Turner’s late period being a compendium of practically all future modernist movements of his and the following centuries. Smiles used historical research to trace how the artist’s life was affected by the contemporary events of his own day and the influences that other artists and writers had on him. He explains how such factors were the causes of his changed style. Smiles sums up some of the main problems with the blanket “late period” assumptions.

As Gordon McMullan has shown, the false attribution of agedness has dogged interpretations of Shakespeare’s later plays, as though The Tempest were the work of an elderly playwright using Prospero’s renunciation of his art to bid farewell to his own profession, as opposed to being written by a man in his forties who collaborated with other writers in three new plays shortly afterwards. Beethoven, likewise, is considered by most commentators to be one of the supreme examples of an artist developing a late style, yet he was only fifty-six when he died. What explains this tendency towards Altersstil interpretations of late works is surely the entrenched notion that the last works of great geniuses disclose profound truths about existence and the human condition and that these sage-like insights can only come at the end of a long creative life.

Paradoxically, however, the idea of a distinctive late phase of production has occasionally been applied to the final works of artists who died even younger than Shakespeare and Beethoven, as for example the idea of late Mozart and late Schubert, even late Keats. . . . The idea that a late style may be detectable in the work of a relatively short-lived artist demonstrates that a strong connection is presumed to exist between intense creativity and feelings of mortality, as though the imminence of death could telescope into a short period the experience an aged artist can command. Alluring as this may seem, it is not something that can be convincingly proved and certainly not for those whose death was unexpected. Furthermore, it aligns late style with an existential predicament above all else: it is the advance of death that is supposed to drive it. . . .

If the relationship of late style to biographical age is opaque, a further problem emerges in connection with its duration. How late is ‘late’? Is the immediate proximity of death essential? If not, how would we limit our exploration of late style? To the last five years of an artist’s activity? Or the last ten? Or would the last twenty years be permissible in some cases?

One might add that the notion of insight gained through growing old is assumed to be a phenomenon shared by all artists, seemingly in a similar way. Surely, however, brilliant artists age in different ways, with a huge variety of reactions to becoming elderly and eventually facing death. Surely also, they encounter all sorts of experiences and obstacles beyond their control that may cause changes of style and theme.

As the case of Turner’s life and legacy shows vividly, simple recourse to designating an artist’s “late period” as an explanation of almost anything that the person does in later life makes it easy to ignore the pertinent, provable circumstances that actually caused changes in his or her work. History is so hard to do.

What can Turner’s career and posthumous reputation tell us about the need to study the contexts of aging filmmakers’ works? For purposes of this discussion, 65 is taken to be the point at which one becomes “officially old” (as Ian McKellen entitled the blog entry he posted on his sixty-fifth birthday) .

Too old to have a late period? Manoel de Oliveira

At 100 years old, Oliveira in 2008 shooting Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl

An obvious place to start is with the Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira. He was born December 11, 1908 and died April 7, 2015, at age 106. He might have had the longest ever career in filmmaking, but he had trouble breaking into the industry and experienced a very slow start. Probably his first film to be completed is Douro, Faina Fluvia, which fortunately survives. It’s a beautiful, short city symphony about his home town, finished in 1931, when he was 23. His first feature, Aniki-Bóbó (1942), was made when he was 34, and his second, Rite of Spring, came out in 1963 when he was 55. In between he had made documentary shorts; in 2019 Il Cinema Ritrovato presented restored versions of two of these. The third, Past and Present did not appear until 1972, when he was 63.

At 63, he should have been on the cusp of a late period, but his career was just picking up steam. He had 28 features and many shorts still to come over the next 43 years. Beginning in 1985 (age 77), he released a feature film nearly every year until 2012. Two shorts followed, one of which came out in 2015 the year Oliveira died. He even made a reflective, modest film about his life, Visita ou Memórias e Confissões in 1982, to be shown after his death. So at the 2015 Il Cinema Ritrovato festival, we saw a “new” and charming Oliveira.

Here we confront Smiles’s problem of how long before death to start the late period. Going by strictly by the 65-year-old rule, that would be with Benilde or the Virgin Mother (1975), released when he was 67. That places nearly all of Oliveira’s features–28 of 31–in his putative late period. Not very useful. But what about style or tone? Can the films be grouped in some way to determine where a director in his 90s or past 100 might finally reach a late period–if at all? Presumably all or most of the films made within that period share some characteristics that mark them as late.

I would suggest a hypothetical test to see if such a distinction can be made from the films themselves, and I will also predict the outcome of that test, since it’s pretty obvious.

Say we show two films by Oliveira to some people who know nothing about him or his films: Francisca and The Strange Case of Angelica. Both are tales of obsessive love on the part of a male protagonist, which helps the comparison. Afterward, ask the subjects which is the film of an old man and which of a young man. If such a test could be arranged, I would bet that most or all of the people asked such a question would pick The Strange Case of Angelica (2010, Oliveira’s 30th feature, released when he was 101) as the film of a young man and Francisca (1981, his sixth feature, aged 72) that of an old man. In the case of Oliveira, at 72 we must count him as a youngish man, at least in the context of his film career.

David and I were lucky enough to see and report on Oliveira’s last three features at the Vancouver International Film Festival. These were Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl (2009), Angelica, and Gebo and the Shadow (2012). Although we pretty much had to mention the director’s age, going back to our reports I was happy to see that we did not treat the films as the accomplishments of an old man.

Discussing Eccentricities, David described the strange device of having characters who are ostensibly talking to each other say their lines directly to the camera. He concluded, “Whippersnapper directors a third Oliveira’s age would not dare so much.”

Of Angelica the following year, I wrote, “The fact that Oliveira was 101 when he made this film, as well as the fact that he is still directing at least a film a year (for last year’s Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl, see here), is too extraordinary not to be remarked on. Yet we shouldn’t let it dominate our view of Angelica or tempt us to treat it as an old man’s film. Slowly paced and meditative it may be, but it is also imaginative and full of humor, despite being centered around a young man’s obsessive love for a dead woman.”

Playing the role of a little old lady: Agnès Varda

Oliveira’s career is almost as anomalous as one can be in the realm of filmmaking. He started very late and kept going very late. Agnès Varda, on the other hand, started young and charged ahead, remaining productive until her death at the ripe old age of 90 (May 30, 1928 to March 29, 2019)–though not always making films.

Varda had established a career as a photographer by the time she directed her first feature, La Pointe Courte (1955), which was released when she was in her mid-20s. It’s a sort of blend of Neorealism, the psychological concerns which were becoming prominent in 1950s art cinema, and her own budding style. The film gained enthusiastic reviews from the Cahiers du cinéma critics but was otherwise largely ignored. Only recently has it gained attention and, ironically, gained Varda a reputation as the grandmother of the New Wave. After her first film’s failure, she made three short films before gaining attention with Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962).

Few would deny that Varda had a late period, and one that can be precisely dated. I believe that she did, but my point here is that late periods can and often do result not from a maturing mental state caused by age. Varda’s late period was caused by her tenuous position in the French film industry and the developing technology of filmmaking.

In 1954, Varda formed Ciné-Tamaris (French for a family of flower-bearing plants known as Tamarisk or Tamarix), her own production company. Most of her films were produced by it, cobbling together funding from a variety of film companies, government subsidy, and European television channels. In this way she kept control of her films from La Pointe Courte to the end. She also managed to be enormously productive, making fiction features, documentaries, and films that seemed to be both at once. She was an independent working largely on the margins of the European film industry.

Then, in 1995, there came a more commercial feature, Les Cents et une Nuits, a relatively big-budget project. It was also made by Ciné-Tamaris with a somewhat larger group of investors providing a bigger budget. It had famous stars, Michel Piccoli and Marcello Mastroianni, in the main roles plus many bit parts and walk-ons involving an amazing group of cinema luminaries. Despite all this, the film failed and thereby caused a crisis in Varda’s life.

My colleague and friend Kelley Conway, an expert on Varda, has summed up the nature and causes of her late period:

Yes, there is a commonly held belief in the scholarly community that Varda really did experience a “late period” that began precisely in 2000.

Three things stand out: her embrace of digital video, her turn to autobiography, and her venture into fine arts. (She become a plasticienne [visual artist], as she often said.)

After the critical and commercial failure of Les Cent et une nuits (1995), she withdrew from filmmaking. She renovated a building on some property she owned in the south of France, created an inn, and appeared to be headed for a pleasant retirement. But then, in 2000 she made GLEANERS AND I, which put her back on the map. She often stated–and I have no reason to believe it’s not true–that she was inspired by digital technology to re-engage in filmmaking.

The “fine arts” that Varda’s urge to create led to were largely installation pieces and photography. She made no films for five years.

Varda expert Bernard Bastide agrees with Kelley’s description and also emphasizes that the availability of small digital cameras enabled to a considerable degree a revival of the earlier phases of her career:

She threw herself into installations because she rediscovered a simpler creativity, linked to her pleasure in “making” and without the necessity to assemble large budgets.

The return to filmmaking was in fact caused by the shift to digital cameras (DV, mini DVD). That moment was a return to her beginnings (lightweight equipment, freedom of movement, etc.) and the pleasure of regaining the playful dimension of the cinema which she had lost with the large production of Cent et une nuits.

The main difference between the digitally-made films that resulted from Varda’s return to filmmaking and her pre-1995 work is, as Kelley points out, a greater autobiographical content. Varda appears in these films, as subject and narrator. (She had appeared in some of her earlier films, but less as the central figure of attention.) This was probably in part a practical decision, since she could work with a minimal crew and replace the actors whom she would otherwise need to pay. As Kelley also points out, however, the late features are not entries in an ordinary autobiography. Here she is writing on the overtly autobiographical The Beaches of Agnès (2008), made when the director was 80:

The very first shot of the film features Varda walking backwards slowly on a beach. She announces, “I’m playing the role of a little old woman, pleasantly plump and talkative, telling her life story.” If Varda is playing the role of a little old woman telling her life story, then the question immediately arises, is this just one of the many roles she could play? [….]

A close look at the style and rhetoric of the film reveals that Varda is not particularly interested in the traditional concerns of the autobiographical documentary, such as the exploration of personal crisis, the critique of the family or socio-political analysis. Les Plages d’Agnès strives, above all, to assert Varda’s status as an active, working, ever-evolving artist, and to memorialize her œuvre in photography, film and installations.

The idea of memorializing her non-film work in particular becomes more prominent in her final feature, Varda par Agnès, where the installations and photography play a large role.

At any rate, Varda does seem to have had a late period, if one that came about through circumstances beyond her control. And yes, there was probably an autobiographical strain in some of the films brought on in part by a growing sense of the end approaching.

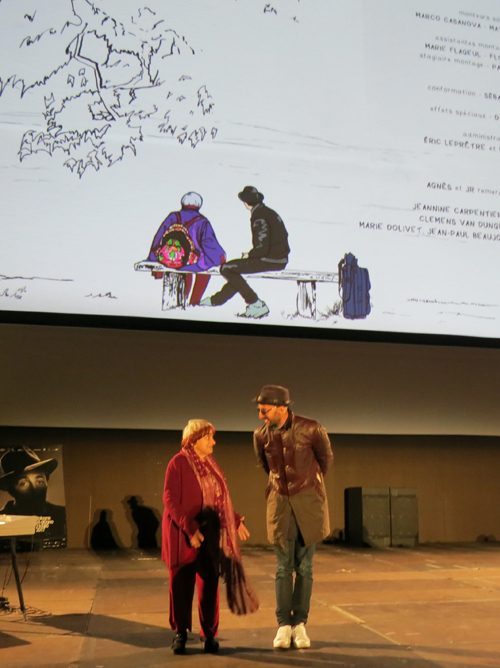

Yet to resort to a cliché, she was one of those people who seemed perpetually young. I met her only briefly twice, but I vividly remember Varda’s appearance at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna in July, 2017. She and her collaborator, street artist and photographer JR, had brought Visages, Villages, which had its Italian premiere as the 10 pm film in the piazza on the last night of the festival. It was hardly a re-found or restored film, the presentation of which is the raison d’être of the festival. But the fact that a brand-new film that hadn’t yet had the slightest chance to be lost or in need of restoration was screening in a place of honor didn’t bother anyone. The standing ovation that greeted the pair afterward (above) went on for many minutes, despite it being past midnight, because the crowd didn’t want to stop sharing the delight that she so obviously felt deeply.

We turned out to be staying in the same hotel as Varda and JR, and we saw them bright and early at breakfast the next morning. We went over to say hello, having met Varda briefly when she visited Madison for a retrospective of her films and a conference devoted to her and her work. We reminded her of this, and though she could hardly have remembered us, she grabbed my hand and held it as JR, David, Varda’s daughter Rosalie, and others carried on a conversation about the thrilling reception of their film. She could hardly have slept more than a few hours, if at all but her energy and eagerness to talk completely belied her age. I’m not sure why she held my hand, but I suspect it was because I happened to be the nearest to her and she was so happy that she wanted to embrace everyone there.

A few brief examples

There are many other directors one could cite, but the point should be clear enough with a few others.

It seems as if Ozu Yasujiro is one of those directors that people love to think of as having had a late period. As I mentioned above, a sure draw as a retrospective would involve Late Spring (1949), Early Summer (1951), Tokyo Story (1953), Equinox Flower ( which gets better every time I see it, 1958), Late Autumn (1960), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962, above). Nearly all of them revolve around the breakup of a family through the marriage of a daughter and involve elderly parents as central or at least major characters (the grandparents in Early Summer). The titles’ trip through the seasons of a year (though An Autumn Afternoon‘s title translates as The Taste of Mackerel) seems to echo Ozu’s own aging over the years, and the assumption probably is that Ozu identifies with the elderly fathers (or mother in Late Autumn) who bow to the inevitable marriage of a daughter. I suspect that many people assume Ozu was quite elderly when he died.

But isn’t all this something of an illusion? With his usual flare for precision, Ozu (December 12, 1903 to December 12, 1963) died at age sixty on his sixtieth birthday. So in fact he fell short of becoming officially old. What we think of as the wisdom achieved in old age seem to have been with him much earlier, perhaps from the start. The comic tone of his early “salaryman” films suggests the cynicism that often comes with long experience.

Consider, too, Tokyo Story, his saddest film. Even earlier than most of his films about young people flying the parental nest, he made a film dealing with what can happen to those parents after the offspring leave. The elderly couple face neglect from their own children and gain consolation only from a daughter-in-law, not their own children (though the grimness is mitigated to some extent by having the youngest daughter still at home.) It’s the only one of these later films where one of the parents dies. Ozu was fifty when it was released.

Despite this seeming consistency of subject matter in these, the best-known of his films, Ozu was making others, quite different, alongside these. Most notably in this context, Ohayu (1959), a very funny film about two boys who engage in farting contests with their friends and go on a silence strike to pressure their parents into getting them a television, came out only three years before An Autumn Afternoon. Equinox Flower is considerably more comic in his treatment of parents and marriageable children than the other films in this group, and the parents are not as elderly as in the other films.

Going back to my idea of showing two films to a group completely unaware of the director’s work, let’s imagine people seeing Tokyo Story and Ohayu and being asked the same question.

Sergei Eisenstein is an interesting case. He died fairly young, just after his fiftieth birthday, in 1948. Clearly he had two different periods, First there were the silent Montage films of the 1920s, from Strike in 1925 to Old and New in 1929. We can’t really judge the years after that, with ¡Que viva México! (1932) being taken away from him before it was completed and Bezhin Meadow (1937), banned and apparently destroyed, though clippings survived and were used to create a reconstruction made up of still frames.

A new period started with Alexander Nevsky (1938) and continued with Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1943) and Part II (banned and not released until 1958). With the Montage films denounced as “formalist” in the early 1930s, Eisenstein changed perforce, to the officially approved genre of epic historical biographies, primarily of pre-Revoluntionary figures interpreted as heroes working toward the spirit of Communism. Ivan was a particular favorite of Stalin, who identified with him. During the late 1930s, Eisenstein managed to avoid the gulag and the firing squad, though many of his colleagues, including the major stage director Vsevolod Meyerhold, did not.

The conditions under which Eisenstein could work and escape such fates demanded that he change his style, and he adopted a new one, though subtly incorporating some principles of the Montage movement and working out new techniques of his own. I suppose these films could be considered as constituting the late period of a middle-aged man, but in this case the impetus came from a very strict and dangerous outside force.

The idea of filmmakers reaching a late period through life experience that gives them greater insight may happen in some cases and is not necessarily a worthless one. Robert Bresson’s early films from Diary of a Country Priest (1951) on centered in some fashion around the quality of religious grace, but gradually his films slipped into a more bitter tone, as exemplified by the grim ending of his version of the Arthurian Legend, Lancelot du Lac (1974), which ends on a heap of dead armor-clad knights. Carl Dreyer’s Gertrud seems to stand apart from his earlier films as the work of an old man.

Yet other filmmakers as great as these seem to have, as it were, their late periods early on. That is, they produced their best work for a time well before old age and then declined to some extent. I know there are people who enjoy and admire Jean Renoir’s later films, say, after The River (1950)–which were made over a span of twenty years. Yet few among them, I suspect, would say that those films rise to the level of his incredible burst of brilliant films during the 1930s.

Renoir’s decline goes against the foundations of the late-period premises that Smiles critiqued in the passage above. The concept depends largely on the idea that the late period comes when artists have gained the insight of age and applied it to their work to impressive effect. The knowledge of upcoming death is partly what spurs, presumably, greater contemplation of the world and the elderly artists’ places in it.

The concept of an artist’s late period can be usefully applied in some cases, but not every artist’s life included experiences or obstacles or opportunities that shaped that period. The misunderstanding and even unjustified appropriation of Turner’s late work for so long after his death provides a warning that when we are attempting to apply the concept to an artist’s creative life, we should not assume that just doing so in itself conveys something meaningful. All this is not to say that Turner did not have a later period. He clearly did. But a study of any artist’s historical context must be undertaken in order to explain how and why that particular artist’s work would change with age–or not.

The Sam Smiles quotation is taken from his excellent The Late Works of J. M. W. Turner: The Artist and His Critics (London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art: 2020), p. 8. The quotation from the smug MOMA curator comes from another excellent Smiles book, J. M. W. Turner: The Making of a Modern Artist (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), which thoroughly takes apart the notion that Turner managed to foresee or even invent virtually every western art movement of the twentieth Century.

Constable’s comment that Turner had a wonderful range of mind is not apocryphal. He wrote it in a letter to his sister. It has often been quoted, including in the title of John Gage’s J. M. W. Turner: “A Wonderful Range of Mind” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987). I would recommend this book as a good place to start learning about Turner. Gage’s Color in Turner: Poetry and Truth (New York: Praeger, 1969) is a rather dry read (it had been his dissertation), but it marked a turning point in the interpretation of Turner’s late work. Coming only a few years after the MOMA exhibition, it revealed Turner as not an eccentric visionary but as an intellectual interested in science and the theory of painting. Turner’s interest in Goethe’s theory was first made known here. Gage’s later book, just cited, expanded his coverage of Turner’s influences as an artist and is presented in a more palatable fashion. Other scholars such as James Hamilton (Turner and the Scientists), Sam Smiles (the two works cited above), and many more followed with similar investigations.

Online jigsaw puzzles can be played and created very easily on jigsawplanet: My own puzzles created from Turner paintings are here. I always make them at the maximum number of pieces, 300, but the flexible site allows you to pick how many pieces you prefer. When you finish the puzzle, the lines between pieces dissolve away, and you are rewarded by a clear image of the painting or object.

My thanks to Kelley Conway for sharing her thoughts on Varda’s “late period” in a recent email discussion. I have quoted the first passages above from that correspondence (March 30-31, 2023). The second quotation, beginning “A close look …” is from her essay,” Varda at work: Les Plages d’Agnès” Studies in French Cinema 10, 2 (2010):126-27. Her book, Agnès Varda (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015), is based on a friendship with the filmmaker, as well as extensive work in published sources and the filmmaker’s own archives.

My thanks also to Bernard Bastide, journalist, film scholar, and teacher, with whom Kelley put me touch. He also offered a summary of the causes for that five-year hiatus in Varda’s filmmaking and kindly allowed me to quote him, using my own translation (email communication, March 31, 2023).

This entry was posted

on Sunday | April 2, 2023 at 1:06 pm and is filed under Film comments.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

[ad_2]

Source link