Die Hard (1988).

David’s health situation has made it difficult for our household to maintain this blog. We don’t want it to fade away, though, so we’ve decided to select previous entries from our backlist to republish. These are items that chime with current developments or that we think might languish undiscovered among our 1094 entries over now 17 years (!). We hope that we will introduce new readers to our efforts and remind loyal readers of entries they may have once enjoyed.

Today’s revival responds to the return of Die Hard to theater screens in time for Christmas. Since our original posting in 2019 (“Not just a Christmas movie”), this supreme action picture has further cemented its reputation as a yuletide favorite (although it was originally released in July). Happy holidays from the Nakatomi Corporation!

DB here:

It’s been quite a fall season for UW–Madison film culture. There were visits from avant-garde legend Larry Gottheim, New York Times co-chief film critic Manohla Dargis, Schawn Belston (Senior VP of Mastering at Disney), and Julia Reichert, whose American Factory is now routinely turning up on ten-best lists. The semester’s first screening at our Cinematheque was Kiril Mkhanosvsky’s Give Me Liberty, a Milwaukee movie also gracing year-end best lists. Our programs included restored films by African pioneer Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, retrospectives of Reichert and Kiarostami, a 3D double feature of Revenge of the Creature and Parasite (no, the other one), a program of early women directors in America, a selection of films conserved by the Chicago Film Society, and a miscellany ranging from Olivia and Near Dark to Tropical Malady and Red Rock West.

Travels to festivals, partly covered in our blog entries, forced us to miss too many of these shows. But we couldn’t miss the final one: Die Hard (1988).

It’s a film I’ve admired since I first saw it in summer of 1988. I’ve taught it in many classes, but never written about it. Seeing it again, in a pretty 35mm print from the Chicago Film Society, has made me want to say a few things as my final blog entry for this busy year.

The man between

Think-piece pundits like to say that Hollywood movies are about good guys versus bad guys. But usually things are more complicated. Very often the good guy is an outsider caught between two large-scale forces, good or bad or both–the cattle ranchers versus the townspeople, or the mob versus the cops. Often the protagonist is an outlier, forced to solve the problem using means that respectable social forces can’t.

Call it the problem of the House Democrats. When the lawbreaker can’t be brought to justice, how do you make him pay? The answer is one that William S. Hart movies provided in the 1910s. We need a “good bad man,” a rogue agent who knows the scheme from the inside but is willing to do the right thing. Which means that he has to be flawed too, a little or a lot, and that he can eventually reform.

In Die Hard, the forces of law and order line up as the Los Angeles police and the FBI. The threat is Hans Gruber’s gang, posing as terrorists but actually planning to rob the Nakatomi Corporation of $640 million in bearer bonds and kill lots of hostages in the process. The naive TV broadcasters support both, recycling official scenarios of how hostage-taking works and reinforcing the gang’s masquerade as a terrorist group.

The contrasts are marked. The forces of order are American, in alliance with a Japanese company, while the attackers are Europeans. At the start, we hear American music (the rap played by the limo driver Argyle), but Hans hums Beethoven. The cops’ technology notably fails, as when the assault vehicle and a helicopter are consumed by firepower. But the gang’s hi-tech expert Theo can crack the vault, assisted by Hans’ plan to push the Feds to cut the building power.

Above all, the forces of social order are strikingly inept, while the gang is ruthlessly efficient. Unlike the police, who “run the terrorist playbook,” Hans boasts that he has left nothing to chance. The cops can’t imagine an adversary that exploits the official by-the-book procedures. As for the business types, Takagi’s calm bluff and Ellis’s freewheeling jargon can’t cope with a gang leader who doesn’t get the Art of the Deal.

Clearly, America and Japan need help. That appears in the form of John McClane, the cop from the East Coast trapped in Nakatomi Plaza.

McClane is the man between, spatially and strategically. He witnesses the action from inside the skyscraper, and bit by bit he figures out the gang’s real scenario. And he’s caught between both forces. The gang tries to find and kill him, while the cops refuse to recognize him as an ally. Confronting Karl’s brother early on teaches McClane that he can’t play by procedure. (“There are rules for policemen,” says a thug who doesn’t believe in rules.) The LAPD’s ineptitude shows that McClane can’t expect help on that front. So he must become almost as reckless as his adversary, though in a virtuous cause. This principally means blowing stuff up.

McClane isn’t totally without resources. He has as helpers Al, the desk cop who comes on the scene and sustains his morale, and Argyle, who’s there to play a crucial role at the climax. But mostly he’s alone in facing problems. He needs weapons. He needs shoes. He needs to protect the hostages, most of all his wife Holly, who has climbed up the corporate ladder. (In another movie, she would be the in-between protagonist.) To keep Holly from becoming a bargaining chip, McClane needs to hide his identity. And he needs to figure out the gang’s ultimate plan, of seeding the rooftop with explosives that will destroy the building and cover their escape.

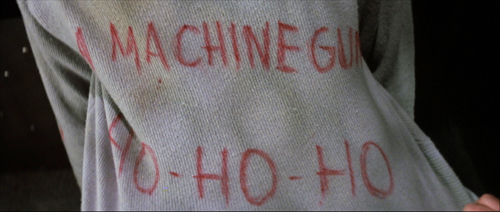

John’s solutions are notably low-tech. While the police and the gang depend on advanced firepower and computer finagling, McClane lashes an explosive to a desk chair and uses a fire hose as a rope. He has to improvise shoes by taping a maxi-pad to a bleeding foot. No holster for your automatic? How about some Christmas wrapping tape? And don’t forget to taunt your adversaries with Yankee wisecracks.

In the course of this drama, the very physical McClane becomes a model for his allies. Holly punches the reporter who revealed John’s identity, and Argyle cold-cocks Theo at the point of getaway. Most dramatically Al kills the revived Karl when he’s about to plug McClane. The people in between take up arms.

McClane and his allies solve the House Democrats’ problem. Law can’t be lawless, even in protecting itself. Business, always aiming at the bottom line, has to give up principles. (“Pearl Harbor didn’t work out, so we got you with tape decks.”) These forces of social order are inefficient, trusting, and superficial. They can’t stand up to sheer brutal onslaught. In a crisis they will fold, or simply choose the nuclear option: agents Johnson and Johnson are ready to lose a big chunk of hostages.

McClane is a mediating figure that permits the film to show you can be strategically lawless for the sake of lawfulness. The fly in the ointment, the monkey in the wrench, screws up plans on both sides, but for the benefit of everyone else.

The Big Dumb Action Picture isn’t so dumb

This thick array of thematic parallels would be interesting in itself, but it gets worked out through precise storytelling. There was a time when critics knocked action movies as simply ragbag assortments of fights, chases, and explosions. Die Hard, I think, changed ideas of just how well-wrought an action picture could be. About 53 minutes of it consist of physical action (including people sneaking around), leaving almost 70 minutes for other stuff: suspense, changing goals, surprise information, attention to parallel plotlines, and little moments like the thief pilfering candy just before an ambush.

The film typifies tidy classical Hollywood construction, beginning with an arrival (the jet) and ending with a departure (the McClanes in a limo). In between we get a big dose of the classic double plotline, romance and work. Holly’s job at Nakatomi threatens their marriage, and John takes on a temp job, that of fighting the gang, which also endangers the couple’s efforts to reconcile.

For every Superman, there’s a Kryptonite, and here the protagonist’s flaws include his fear of heights (set up in the second shot, reiterated throughout) and, more importantly, his resistance to Holly’s independence. By the end, he’s learned a lesson. The film’s streak of male sentimentality allows John to ask his wife’s forgiveness for blocking her career ambition. She’s ready to compromise too, reassuming his last name when she meets Al. The characters we care about change, at least a little. That could be the motto of most classical Hollywood plots.

As usual, we get crosscutting among several lines of action. John’s arrival is crosscut with Holly at work fending off Ellis, and in the rest of the film the gang’s stratagems are intercut with the cops’ plans and McClane’s efforts. At various points, five or six actions are alternating with one another.

All these escalating situations cluster into distinct parts, the four that Kristin has argued for as typical of Hollywood architecture.

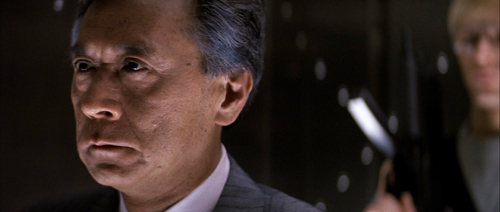

The Setup runs about 33 minutes, culminating in the murder of Takagi and Hans’s promise that he can open the vault.

The Complicating Action, a counter-setup, coalesces around John’s goals of communicating with outsiders, avoiding capture, and attacking the thieves when he can. Through many chases and fights, the gang seeks to block all these efforts. The lines converge when John shoots Marco and tosses his body onto Al’s car. He gains the bag with the detonators, giving him the upper hand. Then the TV reporter gets involved, the cops arrive, and John is ordered to wait. Things seem to be stabilized.

After this midpoint, the Development supplies what Kristin calls “action, suspense, and delay.” Officer Dwayne Robinson arrives, pitting himself against Al and McClane. We can regard the police assault, Ellis’s clumsy attempt to broker a deal, and the arrival of the FBI men as a series of delays that endanger the stability of the standoff. At the end of this section, John meets Hans (posing as an escaped hostage): now both men know each other. And in the firefight that follows, John loses the detonators. Hans declares, “We’re back in business,” and the original plan can go forward.

The last twenty-five minutes constitute the Climax, launched by McClane’s “darkest moment.” He seems utterly beaten. Picking glass shards out of his feet, he gives Al a message for Holly over the CB radio. Al tells of his own burden, the accidental shooting of a child. The stakes are now very high.

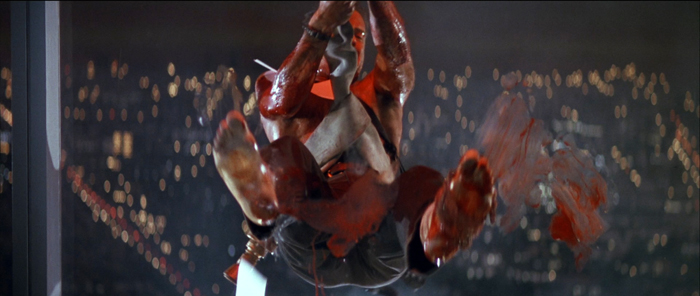

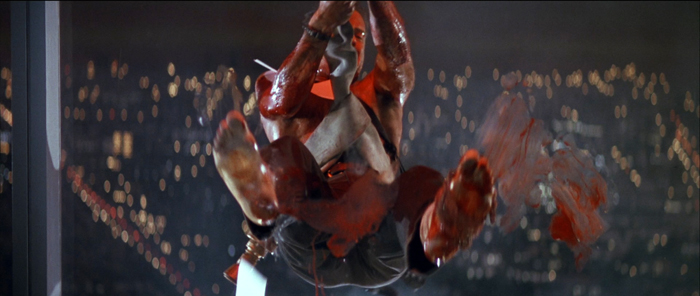

Rapid crosscutting shows John finding the bombs on the roof and fighting with Karl, while the FBI helicopter attacks the building and Hans discovers that Holly is John’s wife. John stampedes the hostages down the stairs off the roof and escapes the strafing from the chopper before it blows. Argyle dispatches Theo, while John finds the surviving gang members in the atrium and shoots Hans, who falls to his death.

In the Epilogue, Al and John meet, Al dispatches Karl, Holly socks the newsman, and John and Holly drive off with Argyle.

These parts present a tight, logically building plot composed of swiftly changing situations. Along the way we encounter a great many motifs that create echoes or contrasts. Everyone notices the Rolex, at first a symbol of Holly’s talents but also of corporate swagger; only by unfastening it can they let Hans drop from the window. When Argyle floats the possibility that Holly will rush back into John’s arms for a movie ending, John murmurs: “I can live with that.” Agent Johnson speaks the same line, but for him it means an acceptable level of civilian casualties.

Holly’s unmarried name, Gennero, shows how a motif can develop in relation to the drama. At first it’s a sign of pride in her own identity (typical corporation, Nakatomi has misspelled it on the touch screen). Her name-change triggers the couple’s quarrel, but it has another narrative use: It conceals John’s identity from Hans. And at the end he introduces her to Al as Gennero but she reasserts her love by correcting him: “Holly McClane.”

Then there are differences of class and country. Hans reads Forbes, but McClane the US boomer references Roy Rogers and Jeopardy. (Hans is so unplugged from pop culture he thinks John Wayne was in High Noon.) Argyle the former cab driver and Al the cop know the downside of city life, but so does John the New York detective, who adapts Roy’s trademark phrase to the mean streets: “Yippee-ki-yay, motherfucker.”

Even a conventional Hollywood gesture, that of attacking a picture of a loved one, acquires a nifty plot function. Annoyed at John, Holly slaps down the family portrait on her shelf. Good thing too, because otherwise Hans would have seen it during the invasion. We’re reminded of that picture when in a moment of quiet John looks at the same snapshot in his wallet. Only after Hans has encountered John is he able to flip the portrait back up and realize that Holly is the “someone you do care about.”

There are lots more felicities like these–so many that I’d consider Die Hard a “hyperclassical film,” a movie that’s more classically constructed than it needs to be. It spills out all these links and echoes in a fever of virtuosity. Hard to believe that the makers started shooting without a finished script.

Intensified continuity, personalized

Die Hard is a good example of a stylistic approach I’ve called “intensified continuity.” It’s a modification of the classical method of staging, shooting, and cutting scenes. Here director John McTiernan and DP Jan de Bont tweak that approach in distinctive and powerful ways. You can find examples all the way through the movie, but I’ll draw most of my illustrations from the first hour, when the stylistic premises get laid out for us.

Cutting speeds accelerated sharply in Hollywood films from the 1960s onward, and for its time, Die Hard was a rapidly-cut movie. The average shot runs just under five seconds, about what you’d get in a 1920s silent film. By today’s standards, which fall more in the 3-4 second range (even for movies outside the action genre), it’s a bit sedate.

One factor that increases the cutting pace is a greater reliance on singles and close-ups. These are tighter than we’d expect in most studio films of the classic era.

Even in close-up, the shots aren’t snipped free of their surroundings, thanks to the wide frame and layers of focus–both important in the film’s overall style, as we’ll see.

Likewise, intensified continuity exploits a greater range of lens lengths than we’d find in studio films of the classic era. We get wide-angle shots like those above along with telephoto shots throughout. Here the long lens is used to pile up people around Holly, and an even longer lens shows her optical viewpoint on the bandits in the office.

And there’s a free-roaming camera, thanks chiefly to Steadicam technology. But interestingly, Die Hard avoids some of today’s most common camera movements, such as shooting a fixed conversation with a sidewise or circular tracking shot. These would become more common in the 1990s.

McTiernan thought a lot about his camera movements, as he explains in interviews and the commentary track on the DVD. He wanted to shape spectators’ attention, to use camera movement to nudge things into view. “The audience’s eye wants to go with you.” Accordingly, more than in many contemporary films, Die Hard‘s camera movements have a shape: they end on a point of information.

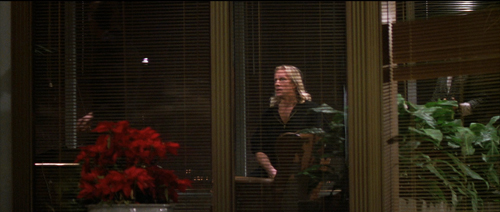

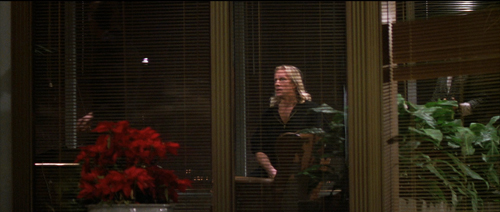

Sometimes it’s just a quick pan, doing duty for a cut. At other times, the reframing is a gentle nudge that prepares for a new scenic element, as when Holly enters her office.

In shooting Predator (1987), McTiernan wanted to cut moving shots together, but his editor resisted. For Die Hard, he refilmed his camera movements at different rates so that two would match. A good example is when Karl’s brother strides carefully into an area under construction. The camera tracks with him, but when he turns to find the source of a whining noise, the arcing movement at the end of one shot is picked up in the next as the framing circles to reveal the saw.

That reveal is given, characteristically, in rack focus. I could have added rack focus as another featured technique of intensified continuity. McTiernan and de Bont take it very far, making Die Hard one of the great rack-focus movies. The image is constantly shifting focus to guide our attention to the changing layers of the scene.

This neat, compact presentation not only preserves the commitment to long-lens close-ups we find in intensified continuity. The technique also gives each rack focus the snapping force of a cut. (And you don’t need to build big sets.) Needless to say, the rack-focusing wouldn’t work if McTiernan hadn’t committed himself to staging his action in depth. More on this below.

Staging in ‘Scope

Die Hard finds ingenious ways to “let the audience’s eye go with you” in the widescreen format. Sometimes it’s a matter of classic edge framing. Thanks to a low angle, John and Holly converse along a wide-angle diagonal.

Sometimes McTiernan reverts to a technique not enough directors use nowadays: blocking and revealing. In classic cinema that was usually a technique reserved for long shots, when actors could move aside as part of ensemble. Die Hard applies blocking and revealing to the tight framings of intensified continuity.

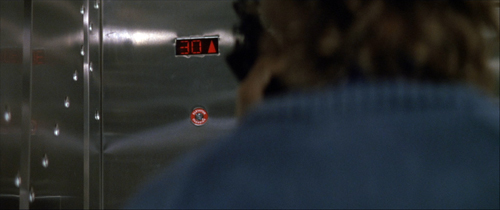

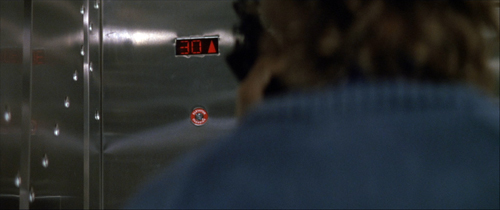

A thug in an elevator checks his weapon, pivots for an instant, and then moves aside to show the elevator arriving at the target floor.

Here again a rack focus helps. The moment reiterates the importance of the thirtieth floor in the skyscraper’s geography.

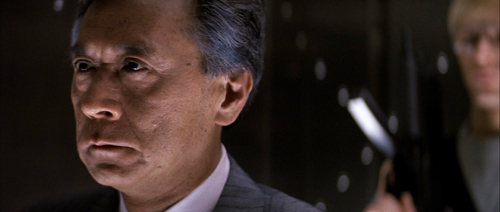

When Hans finds the body of Karl’s brother, we can study his expression. He flips the victim’s head to reveal a gunman, who looks to Hans before he says his line.

In a neat touch, the thug’s mouth isn’t shown. Today a director would probably show his whole face, but, really, who cares? The careful framing keeps him a secondary character, and a future target of McClane. And no need to rack focus on him, which would give him unwonted importance. All we need to remember him is that he’s the thug with long hair.

I can’t refrain from using one audacious example from late in the film. John and Hans have met, and Hans has revealed himself by targeting John with the pistol McClane has given him. In reverse shot, John reveals that it has no bullets and grabs it away from Hans.

But the pistol, and that gesture, have concealed the elevator behind them. When the pistol is knocked down, the elevator light pops on in the background. Our attention snaps to it, aided by that characteristic ping we hear throughout the movie (another motif).

The crisp turn of events, given visually and sonically, gets ampified by the acting. McClane’s cockiness turns to panic and Hans gets the upper hand. (“Think I’m fucking stupid, Hans?” Ping. “You vere saying?”)

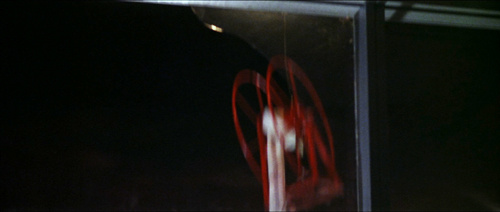

The most bravura rack-focus comes during the climax, when the firehose reel whizzes down behind McClane and he realizes that he’s being dragged through the shattered window.

The coordination of the long lens, camera movement, staging, and racking focus is especially rich when Hans drifts among the hostages searching for the man in charge. He recites Takagi’s life history as he passes from one possibility to another (including, comically, Ellis).

At the climax of the passage, McTiernan’s staging-in-layers sets up Takagi, Karl, and Holly before Takagi takes charge. Briefly blocked by Hans, he admits his identity by stepping out from behind and into focus.

McTiernan isn’t done. A reverse shot of Hans finishing his spiel (“…and father of five”) punctuates the suspense. McTiernan buttons up this passage by returning to his “moving master” shot and having Karl shove Takagi out.

That clears the way for us to see Holly’s reaction. A beat dwells on her as she shifts her eyes to Hans, foreshadowing her conflict with him at the climax.

This sort of layering of faces popping in and out of visibility has precedents in earlier cinema, chiefly of the “tableau” period of the 1910s. McTiernan has, I think, spontaneously rediscovered for modern times what William C. de Mille was up to in the party scene in The Heir to the Hoorah (1916). (For more on that, go here.)

Of course McTiernan also has to work with the 2.35:1 anamorphic format, which enables him to spread his layers out more. That format also allows some remarkable compositions, such as the one surmounting today’s entry. The cut to the shot of John in Holly’s office uses the abstract splash painting (seen here for the first time) as a visual analogy for the explosion of gunfire offscreen at the same time.

McTiernan and de Bont constantly find striking but cogent images, thanks to lighting as well as color and format. Here’s McClane on top of an elevator peering through the perforated grille; his POV is a striking but still informative composition. the cut between the two provides a little punch of contrasting light and shade.

There are felicities like these feathered all through this remarkable movie, but the momentum of storytelling never flags. This remains a masterpiece of Hollywood filmmaking.

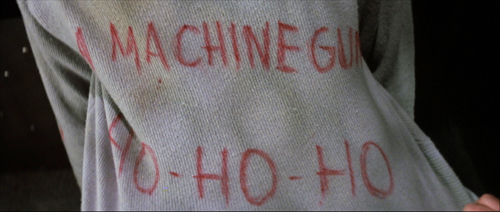

Thanks to our readers for following us this year. Kristin will be weighing in soon with her annual list of best films from ninety years ago. In the meantime, HO-HO-HO.

Madison owes an enormous debt to our Cinematheque team: programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, Ben Reiser, and Zach Zahos, as well as veteran projectionist Roch Gersbach. Santa should reward them. You can too by visiting the Cinematheque’s Podcast, Cinematalk. There you’ll find conversations with Manohla Dargis, Schawn Belston, and James Runde.

For lots of background on the making of this film and the four sequels, there’s Die Hard: The Ultimate Visual History by Ronald Mottram and David S. Cohen. At rogerebert.com, Matt Zoller Seitz has a discerning appreciation on the occasion of the film’s twenty-fifth anniversary.

Jake Tapper has provided the definitive analysis of Die Hard as a bona fide Christmas movie.

McTiernan (with whom I share an alma mater) provides very good DVD commentaries (even for Basic). Prison also seems to have given him some pronounced political views. Alas, the website he created as a platform for them is apparently no longer available. Word is that McTiernan is preparing a new film, Tau Ceti 4, with Uma Thurman. A videogame promo is purportedly signed by him.

Of other McTiernan films, I also much admire The Hunt for Red October (1990). The Thomas Crown Affair (1999) seems to me better directed than the original, and The 13th Warrior (1999), despite being taken out of his hands, remains a pretty interesting film. (Name another Hollywood movie in which a Muslim poet visiting Northern Europe is justly appalled at its barbarism.) Nomads (1986) also has its good points.

I discuss the issues of narrative and style raised here at greater length in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. You can also search “intensified continuity” for blog entries hereabouts. On CinemaScope aesthetics, see this entry and this video.

Die Hard (1988).

Last Modified: Monday | December 4, 2023 @ 22:32  open printable version

open printable version

This entry was posted

on Monday | December 4, 2023 at 12:39 pm and is filed under Directors: McTiernan, Film comments, Film genres, Film technique: Editing, Film technique: Staging, Film technique: Widescreen, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, Narrative strategies.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

1976 Aardman Animation founded.

1976 Aardman Animation founded.

1989 Lip Sync series: Next (dir. Barry Purves; left), Ident (dir. Goleszowski; first appearance of Rex the Runt), Going Equipped (dir. Lord), Creature Comforts (dir. Park), War Story (dir. Lord) Channel Four.

1989 Lip Sync series: Next (dir. Barry Purves; left), Ident (dir. Goleszowski; first appearance of Rex the Runt), Going Equipped (dir. Lord), Creature Comforts (dir. Park), War Story (dir. Lord) Channel Four. 1991 Adam (Lord; right).

1991 Adam (Lord; right). 1994 Pib & Pog (dir. Peter Peake; left).

1994 Pib & Pog (dir. Peter Peake; left). 1997 Dreamworks pre-buys the U.S. rights to Chicken Run.

1997 Dreamworks pre-buys the U.S. rights to Chicken Run. 2001 Rex the Runt (dir. Golwszowski; left) second season, BBC2, 13 episodes, aired September to December.

2001 Rex the Runt (dir. Golwszowski; left) second season, BBC2, 13 episodes, aired September to December. American viewers restricted to Region 1 DVDs have far less available to them. The American DVD of Creature Comforts (now out of print) contained only three other Aardman films: Wat’s Pig, Adam, and Not without My Handbag (left)—among the best, no doubt, but far from the cornucopia on Aardman Classics.

American viewers restricted to Region 1 DVDs have far less available to them. The American DVD of Creature Comforts (now out of print) contained only three other Aardman films: Wat’s Pig, Adam, and Not without My Handbag (left)—among the best, no doubt, but far from the cornucopia on Aardman Classics.