David’s health situation has made it difficult for our household to maintain this blog. We don’t want it to fade away, though, so we’ve decided to select previous entries from our backlist to republish. These are items that chime with current developments or that we think might languish undiscovered among our 1094 entries over now 17 years (!). We hope that we will introduce new readers to our efforts and remind loyal readers of entries they may have once enjoyed.

Movie fans may want something a little offbeat relax with at home, so we thought that in these turbulent times, classic comedy would be welcome. We’ve picked a 2017 entry to revive (and slightly revise): “The Boy’s Life,” devoted to Harold Lloyd. (He certainly had the holiday spirit; he’s said to have kept a Christmas tree up, complete with presents, all year round.) We still think he rewards our interest, and families and cinephiles ought to find his films fun. This entry introduces Girl Shy, still running on The Criterion Channel, with DB’s discussion included there. The blog entry refers to other Lloyd movies, all of which are on the Channel and some of which are also available on the TCM wing of Max (but not, alas, Girl Shy).

Warm holiday wishes from the two of us!

DB here:

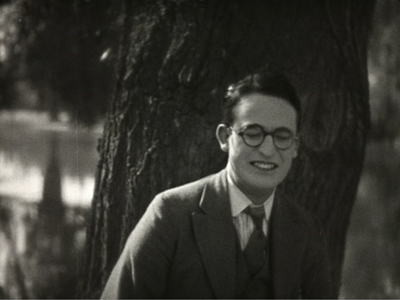

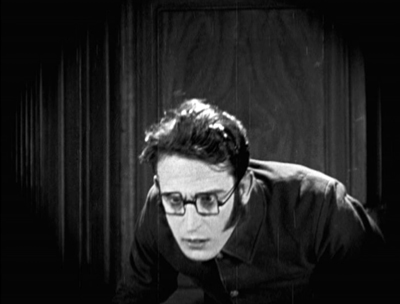

On 9 September 1917, film history changed for the better. That was when we got the eyeglasses.

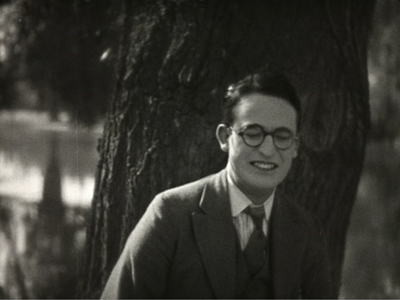

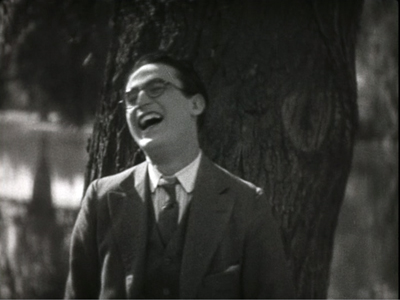

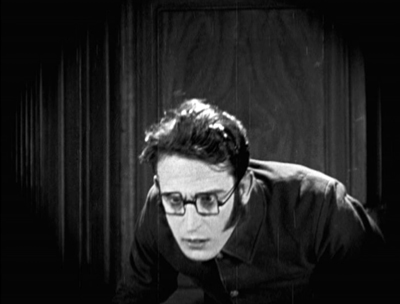

Their circular, horn-rimmed frames stood out as wire rims would not; besides, horn rims had become fashionable for young people. These specs held no lenses, but so much the better. Reflections from studio lights would have hidden the eyes of the winsome, earnest, clueless young man usually called the Boy.

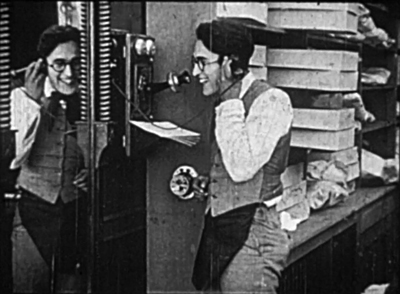

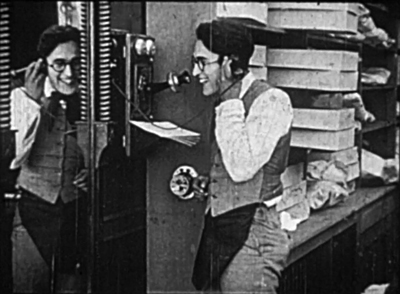

In Over the Fence, the film introducing him, he’s already amiable, a little vacuous but delighted to be talking to his girl on the phone and watching himself doing it.

Harold Lloyd had already featured in some sixty-five short comedies from 1915, playing characters called Willie Work and Lonesome Luke. Even after introducing the Boy, Lloyd continued with a few Lukes before phasing out this sad sack. No one expected that in a few years the glasses character would become world famous. Lloyd’s films were more lucrative in aggregate than those of any other silent comedian, and he became one of the central figures in Hollywood.

When our comrades at Criterion announced their plan for a centenary Lloyd celebration this month on FilmStruck, I suggested we devote an installment of our series to one of the films. Kristin and I have been Lloyd fans for decades. Fans and collectors kept his work alive. Kevin Brownlow had to remind people with his Lloyd documentary, The Third Genius (1989), that, well, Lloyd was a genius. The more you get to know his work, the better it looks, and the less plausible seem many of the clichés that have clustered around it.

One of the very best films to get to know is Girl Shy (1924). That’s the one analyzed in the latest Observations on Film Art episode on the Criterion Channel.

Man into Boy

For decades after sound came in, American silent comedies dropped mostly out of sight. Some 16mm copies were available in cut-down rental versions, and a few were circulated by the Museum of Modern Art Film Library. (Of Lloyd’s work, that included only The Freshman of 1925.) The MoMA canon became the canon. In the 1970s, thanks largely to piracy, the films of Keaton were added, and still later we came to recognize Charley Chase, Max Davidson, and other talents.

Throughout these years Lloyd’s films were almost invisible because he controlled the rights to them and limited their circulation. Kept in vaults in his rococo estate Greenacres, they would not reemerge until the 1960s, in cut TV versions distributed by Time-Life. Until fairly recently, most critics relied on memory of the films and the received image of the Boy dangling helplessly from the clock face.

Most of the sixty-one shorts featuring the Boy languish in archives, and some were lost in a fire on the Lloyd estate. But several two-reelers are readily available, as are all the longer films. What we have gives the lie to most clichés about this filmmaker.

Take the most persistent one. Socially conscious critics of the 1930s saw Lloyd’s work as naively reflecting the go-go 1920s. The Boy’s resolutely middle-class aspirations made him a crass avatar of complacency before the Crash. Chaplin seemed to stick up for the little guy, but Lloyd seemed to celebrate the striver; he compared himself to Tom Sawyer. It was all very neat. The Boy’s climb up the skyscraper in Safety Last could symbolize the heedless ambition of the white-collar worker, while the his efforts to fit in at college in The Freshman suggest desperate American conformity.

Those interpretations played down the fact that just as often Lloyd played hayseeds humiliated by city folk and con artists. In Girl Shy, the city slicker who wants the girl is a weasel, and Harold has to rescue her. Here, as often, the film is largely a procession of social humiliations. Lloyd, a predecessor of cringe comedy, in turn provided a model of embarrassment for Ozu’s silent films. Those films often feature students wearing the Boy’s glasses (below, Days of Youth, 1929). This isn’t mere imitation or homage; the glasses became a Japanese fashion item, called roydo, named after Lloyd. (Below, a photo from a student ski trip in the 1930s.)

More edgily, Lloyd also played foppish idlers, louche one-percenters who glide obliviously through the lower orders and need to learn humility. The original title of For Heaven’s Sake (1926) was to be The Man with a Mansion and the Miss with a Mission, a phrase retained in an intertitle. Here as elsewhere, the coddled Boy learns to help his social inferiors. If you’re after class-based critique, Lloyd films come out pretty well.

Likewise, there were the complaints that Lloyd’s comedy was mechanical. Chaplin was the poet and dancer. Keaton, in both concept and execution, showed himself a geometer, the dogged engineer of monumental effects more awe-inspiring than hilarious. Though granting that Lloyd, foot for foot, yielded more laughs than any of his peers, critics worried that he was only merely funny, a relentless gag machine. Here is James Agee, in one of the subtlest appreciations of silent cinema ever written:

If great comedy must involve something beyond laughter, Lloyd was not a great comedian.

But immediately, as an honest man, Agee must add:

If plain laughter is any criterion—and it is a healthy counterbalance to the other—few people have equaled him, and nobody has ever beaten him.

Still, Agee admits that Lloyd’s films pass beyond laughter in one respect. They offer harrowing suspense. What his audiences called “thrill comedy” remains chilling today. His antics on skyscraper ledges and girders still induce vertigo, and his car chases risk catastrophe on a scale that would worry Jackie Chan. Agee seems to grant that inducing shrieks as well as guffaws is no small accomplishment.

If Agee could have reviewed all the feature films, though, maybe his judgment wouldn’t have been so absolute. For example, Lloyd’s features take us beyond laughter in serious ways—into regions of vulnerability and inadequacy. The Boy is typically given a fault: cowardice (Grandma’s Boy), self-absorption (as hypochondria in Why Worry? and as self-indulgence in For Heaven’s Sake), lack of confidence (The Kid Brother), neurotic extroversion (The Freshman). In several films, the seriousness undercuts the comedy.

In Grandma’s Boy, Harold can’t drive away the tramp, but Granny can do it easily, with some swipes of her broom. Our laughter is cut short when, in the space of a cut, as she calmly returns to the porch, we see the Boy slumped over, his head in his hands.

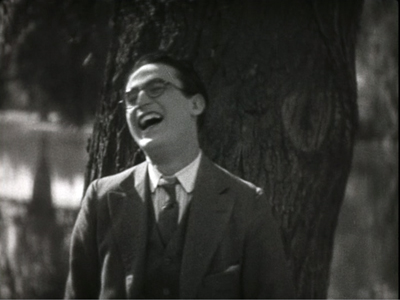

Soon he will admit that he’s a coward. Lloyd films switch their tone on a dime, shifting between comedy and drama breathlessly. In Girl Shy, the Boy not only dumps the girl he loves but does so by cruelly laughing at her trust in him. (Agee: “He had an expertly expressive body and even more expressive teeth.”) Wobbling and shifting his weight, Harold breaks the laugh with a gulp before carrying on his bluff.

Nothing in Keaton or Chaplin makes us as ashamed of our hero as we are right now. Soon he will do something worse.

This passage reminds us that Lloyd worked his face for all it was worth. Keaton had more expressions than he’s usually credited with (bewilderment, concentration, doggedness); it’s just that he doesn’t smile. Chaplin inherited the white-face clown tradition and often favored deadpan. He limited his facial reactions to squiggles and flashes, often no more than a skew of the mouth or hauteur in the brows, with an occasional embarrassed giggle. With Chaplin, the body expresses nearly everything, as befits an aesthetic predicated on the long shot.

But Lloyd, relying on medium shots, performs as a dramatic actor, with a wide repertory of expressions. Agee refers to his “thesaurus of smiles,” but he had other resources, as this Girl Shy scene attests. His producer Hal Roach is said to have remarked: “Harold Lloyd was not a comedian. But he was the finest actor to play a comedian that I ever saw.”

Another nuance: Comic laughter comes in many varieties. Like Keaton, Lloyd celebrates winning through tenacity and resilience. If we gasp at the geometrical audacity of Keaton’s humor, we’re buoyed by Harold’s righteous settling of accounts. It’s reported that audiences actually leaped up and cheered at the climaxes, when bullies and rascals were punished at delectable length. These are comedies of comeuppance and payback, outcomes universally enjoyed and still much in demand today.

Point the last: Neatness of construction. Chaplin’s films are lovably episodic; I still marvel that films that took so long to make are so loosely put together. Keaton by contrast is a metronome-and-protractor director, aiming to make every shot and sequence and reel sit in meticulous order. No one but he could have conceived the marvel of symmetry that is The General, or, on a lesser scale, Our Hospitality and Neighbors.

Lloyd’s films are no less finely put together, as many recognized at the time. A Film Daily review of The Kid Brother (1927) noted: “Lloyd and his gag-men again have devised a corking set of comedy situations that fit consistently into a well-joined plot and laughs keep building from little chuckles to hilarious roars.” Orson Welles praised “the construction of Safety Last, for instance. As a piece of comic architecture, it’s impeccable. Feydeau never topped it for sheer construction.”

To get a little more specific, I think that Lloyd’s model was the well-made dramatic film, the tight classical plot. This is the argument I make in the Girl Shy installment. I try to show that in this, his first film as an independent producer, Lloyd applied the emerging model of Hollywood narrative to feature-length physical comedy. Fairbanks had moved in this direction, and Lubitsch would achieve something similar with social comedy in The Marriage Circle (1924) and the masterpiece that is Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925).

Lloyd was a pioneer in showing how everything that worked for serious dramaturgy could work for comedy too. Girl Shy gives us a goal-oriented protagonist who has a serious flaw. Going beyond the figures of slapstick, we get access to his psychological yearnings and frustrations. His loneliness and fear of women fuel overwrought fantasies of domination. The Boy is caught up in the characteristic Hollywood double plot, involving love and career—two lines of action that usually block and deflect one another.

This linear action is deepened by a series of motifs. They’re simple in themselves (a stammer, a Cracker Jack box, a dog biscuit box), but they’re worked out with a pictorial and dramatic intricacy that’s rare at the time. And it’s all topped off by a two-reel chase that is simply one of the greatest ever put on the screen. At a time when every superhero blockbuster ends with a big action sequence, it’s worth seeing one that’s both graceful and hilarious, and it owes nothing to special effects.

Girl Shy shows how rewardingly complex silent Hollywood storytelling could be. It reveals Lloyd as a master craftsman of cinematic resources—dramatic, pictorial, emotional. He saw how to make a movie that would be engrossing even without the gags. The comedy deepens a powerful dramatic premise that moves forward with an organic, not mechanical, energy, and it’s developed in funny or poignant detail at every instant.

Filling the format

In the arts, form often follows format. The fourteen-line sonnet, the tondo painting, the twenty-two-minute sitcom, the nine-panel comic-book page: all provide the artist with a set framework within which to create. When Lloyd started out, film reels in the US were standardized at 1000 feet, which typically ran between twelve and fifteen minutes, depending on projection speed. Short films, particularly comedies, were either one or two reels, while features–dramas, mostly–ran four, five, or more.

The task of the filmmaker was to build a story that would fit the format. The temptation was padding. Griffith, for instance, often filled out his shorts with “goings and comings,” shots of characters leaving one place and making their way to another, sometimes across several shots. But once padding was inserted, filmmakers could make it engaging. Griffith did this by embedding the goings and comings in suspenseful situations, so that the travel shots served as dramatic delays. Mack Sennett needed scenes to lead up to a big chase (the “rally”), but those scenes could themselves have a linear logic, as with romantic rivalry or street quarrels.

Lloyd became very sensitive to film length. He knew that his initial popularity depended on the fact that Pathé and producer Hal Roach spit out a Lonesome Luke every week or two; he saturated the market. Even after Luke appeared in two-reelers, Lloyd wanted his new character, the Boy, to start in one-reelers. He recalled telling Roach, in sentences as breathless as the pace of a one-reeler:

Now, I’m getting started in a new character and you want people to get used to the character, you want them to see the character; and besides, if you make a poor, or mediocre, or moderately good, or even a bad picture in a two-reeler, it’ll kind of tend to sour the people on you because they won’t see another one for a month. But if I make one-reelers, we’ll get one out every week, so if a couple of them are not so good, and the third one is, it will cover up the other two, and besides it will keep you in front of the public.

As a result, Lloyd spent two years turning out an astonishing eighty-two one-reelers. Not until Bumping into Broadway (2 November 1919) did he launch a two-reeler featuring the Boy.

There’s evidence that Lloyd’s awareness of the niceties of running times went beyond a concern for building the brand. He understood that form and format had to mesh. His early one-reelers relied largely on the standard episodic knockabout. We’re given a defined situation, such as a modernized hotel (The City Slicker, 1918), a western saloon (Two-Gun Gussie, 1918), or a vaudeville theatre (Ring Up the Curtain, 1919). In this situation, the characters quarrel, pull pranks on one another, engage in fistfights, kick each other in the pants, and usually wind up in a chase. A string of gags might emerge, as when a stray snake terrifies the theatre troupe in Ring Up the Curtain, but the gag is quickly exhausted, and we go on to the next bit.

Once Lloyd settled on two-reelers, he built them up more carefully. He scaled, we might say, his plots and gags to a fairly tight, logical development in the fuller format. Part of that development involves what we might call nested gags. In Captain Kidd’s Kids (1920), the first part (roughly one reel) sets up Harold as a playboy recovering from a bachelor party. In his elaborate bathroom, he tips back his chair, leading us to expect him to fall in. But no: instead his butler, Snub Pollard, dumps ice in the pool.

There follows a string of shaving gags here and in the next room. Early in this series, Harold drips shaving cream in his morning tea; but after other gags he comes to drink it and finds it foul-tasting. Then he returns to the bathroom, tips back the chair again, with results we’d expected several minutes before.

Now we get some elaborate efforts to rescue Snub. The gags are simple, but by setting up one and then moving to set up and pay off others before returning to the first, Lloyd and his team avoid the start-stop-restart pattern than we find in many one-reelers.

The real plot action, of course, doesn’t get going until the second reel of Captain Kidd’s Kids, but Lloyd has provided some lively padding to start. Now or Never (1921) shows the same gag-braiding, with the recurring appearance of two drunks on the train ride that constitutes the bulk of the film.

Lloyd moved toward longer films cautiously—first to three reels, then four (A Sailor-Made Man, 1921), then five (Grandma’s Boy and Dr. Jack, 1922). He always said that most grew organically, beginning as two-reelers and then expanding when the story premises and gag sequences developed. To keep things in proportion, he tested the results on preview audiences, then reshot and recut his footage. The preview responses to one three-reeler, I Do (1921), convinced him to lop off the entire first reel. Although he had increased confidence in his ability to scale up, when he signed a new contract with Pathé in early 1922 he insisted that the company publish a notice to exhibitors declaring that film length would be

strictly governed by the character and quality of the material evolved in the production development of each subject—which means that the Lloyd standard of excellence is to be maintained first of all; a given story that turns out to be adequately filmed in two reels will be confined to two reels, and so released. This is a principle cherished by Lloyd himself.

Lloyd could be so confident because even his shorter releases were becoming the top-billed item on programs across the country. He was, in effect, returning the idea of “feature” to its original meaning—not simply a long film, but rather a movie that could be “featured” in publicity. He was also announcing his unusual concern for tight form.

Comic architecture

Grandma’s Boy (1922).

Lloyd moved to features in synchronization with his peers. Keaton was the first, with The Saphead (September 1920), though it’s less a comedy than a light drama; and Keaton returned to making two-reelers for three years. The Round-Up (October 1920) gave Fatty Arbuckle a comic role in what was basically a serious drama. Arbuckle starred in The Life of the Party (December 1920), another light drama with almost no physical comedy. Chaplin’s The Kid (February 1921), at a bit more than five reels, might be considered the first slapstick feature since the one-off Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914, six reels). The émigré Max Linder got into the act with two 1921 features, Seven Years’ Bad Luck (May 1921) and Be My Wife (December).

It might seem that Lloyd was a bit late with the four-reel Sailor-Made Man (December 1921). But that film capped his most extraordinary year to date, with four earlier films released in spring, summer, and fall. Along with six two-reelers released in 1920, Lloyd was now a major comedy star, and the Boy could carry a longer story.

But how to do that? His peers explored some options. In Arbuckle’s two features, it’s his physical presence that matters, not consistency of character; in one he’s a genial sheriff, in the other a lawyer inclined toward crookedness. Chaplin retained the Tramp persona in The Kid, but the film is a rather episodic affair. Once the main plot is resolved, a reel pads out its length with a dream sequence set in heaven. The Linder films are lively but digressive, with plots propelled by casual pranks and lovers’ misunderstandings.

By contrast, Lloyd’s features moved toward tight construction. Despite his claim that his films just grew longer accidentally, they were shaped in ways that make them seem through-composed. His comedy sequences are deftly prolonged, building and topping themselves with great speed. Gags are embedded and interwoven in ways that yield surprises, and motifs set up early in the film pay off later. We may have forgotten about them, but Lloyd hasn’t.

Lloyd’s obsession with overall form can be seen in his use of the “Lafograf,” a kind of EKG of viewers’ response at previews. Coders sat in the audience with pencil, paper, and stop watches to note every bit of amusement, from a titter to a screech. Once graphed, the entire movie displayed laughs big and small throughout, with most of the big ones spiking in the last reel.

A powerful demonstration of Lloyd’s skill came in his first five-reeler, Grandma’s Boy (1922). Chaplin called it “one of the best constructed screenplays I have ever seen on the screen.” Lloyd began it as a two-reeler, but after expansion it had become more drama than comedy. Roach urged him to add more gags, and the result is a remarkable balance between humor and pathos.

That mixture is given from the start in a prologue showing a baby Harold, glasses and all, bullied by another baby. Then the Boy as a boy is picked on and made to put a chip on his shoulder.

This last bit will pay off fifty minutes later. The rival, the little bully grown up, taunts Harold, not knowing Harold has captured the prowling tramp and proven his courage.

The upshot is a fight that knocks the stuffing out of the Bully. In the course of that fight, another moment calls up a contrast with an earlier scene. The day before, the Bully has pitched Harold into the well; now, after the Rival tries a foul blow, Harold administers payback.

These distant echoes can be very satisfying.

The organization of gags is likewise remarkably sustained. Walking home from his well dunking, Harold finds that his one suit has shrunk grotesquely. But the Girl has invited Harold to her home for an evening, so he needs another suit. Granny digs out his Grandpa’s suit, 1862 vintage. (The peddler said it was unique.) It still has mothballs in it. Granny also finds there’s no shoe polish, so she uses goose grease instead. These bits become the basis of a steadily building gag situation in the Girl’s parlor.

But not right away. First Harold arrives and discovers that his vintage outfit is matched by that of the butler. Another echo, when he mutters: “That peddler lied to Granny!” He sits to listen to the Girl play the piano, and gets his finger caught in a vase. Only now does one of the earlier gag setups start to pay off. A cat comes to lick his tastily greased shoes.

The grown-up Bully was introduced throwing a stick at a cat, but Harold is more gentle. He nudges the Girl’s cat away, but soon a troupe of cats enters to converge at his feet.

He has to dispose of them without the Girl’s noticing. Finally, when the couple move to the settee, the cats reconnoiter and the gag sequence pays off: Harold uses a statuette of a bulldog to scare them away.

Cozying up to the Girl, Harold ought to be in clover, but now she smells something—his suit. Investigating, he finds mothballs that he and Granny failed to remove. I’ll spare you more description. You can watch what happens next, including a new confrontation with the Rival. And again, Harold gives us an unforgettable suite of facial expressions.

Lloyd’s pacing allows just enough time for us to anticipate what might happen at each turn of events. Structurally, while Lloyd is developing and paying off the IOU of the mothballs, he wedges in a fresh setup, that of the neighbor kid’s requesting some gasoline. That becomes the topper for the mothball series, as the dog statuette topped the cat gags. This sort of braiding of gags, weaving the setup of one gag into the development of another, shows how a feature can be built out of quasi-melodic lines, like a song.

Even more important is the presentation of the protagonist. Lloyd gives his hero what modern screenwriters call a character arc. In the early 1920s Lloyd began to distinguish between gag pictures and “character pictures,” in which the story line depends on our concern for the protagonist.

In his short films, Harold had an established image, but his characterization varied a lot. Sometimes he was a good-natured everyman, but he could also be a scrapper, a hustler, or a ne’er-do-well. And his romantic relations with Bebe Daniels were wonderfully flirtatious; in one she helps him count bills by licking his thumb. In the features, Harold was given a more definite character, one with a pronounced fault. He was often insecure, awkward, and oblivious, qualities that led critics to call him a boob. The insult is referenced in Girl Shy, when his book gets mocked as The Boob’s Diary. Correspondingly, the romance plotline of his films became much more fraught.

In Grandma’s Boy, Harold’s fault is cowardice, and he must keep the Girl from finding it out. His impulse is to hide from the world, but Granny inspires him with the tale of how his Grandpa overcame his fears and helped the southern army win the war. He did it, she says, thanks to a Zuñi charm given him by an old woman.

Now Grandma gives Harold the charm, and his faith in it enables him to capture the murderous thief. In a double climax, Harold, still clinging to the charm, is able to beat the Bully in a drag-out fistfight.

Of course the action is packed with delays, detours, and surprises. The capture of the thief is a superb flow of gags, from Harold braving the tramp’s hideout to a long chase, in which the talisman does duty as a pistol barrel. And the fight with the Bully gets expanded when Harold loses the charm and turns suddenly meek. After the fight, the topper comes when Granny reveals the real source of the charm’s power. Harold comes to understand that he has inherent reserves of courage.

Nicholas Kazan once observed: “You want every character to learn something. . . . Hollywood is sustained on the illusion that human beings are capable of change.” This principle of construction goes very far back, and it became the basis of Lloyd’s feature plots. We get not just a change of fortune (and so a happy ending) but a change in personality (and so a happier one).

From Grandma’s Boy onward, Lloyd’s features display disciplined, inventive construction–at the macro-level of plot and at the mid-range of gag sequences, down to precise shot-by-shot articulation of the action. Here’s a moment when Grandpa (he wears glasses too) sees, reflected in an inkstand lid, a Union officer preparing to clobber him.

Since the Bully is reincarnated in the Union officer Harold outwits, this flashback quietly prefigures the Boy’s victory over the Bully at the climax.

In my Criterion Channel presentation, Girl Shy serves as another example of how Lloyd brought classical construction to comedy. I could as easily have picked another superb item, The Kid Brother. Maybe next year?

It seems likely that Lloyd’s work became a model. Keaton’s trimly carpentered second feature Our Hospitality (1923) is in the same vein. And Chaplin, after he praised Grandma’s Boy, went on to declare: “The boy has a fine understanding of light and shape, and that picture has given me a real artistic thrill and stimulated me to go ahead.” Lloyd and the Boy, glasses and all, remade Hollywood comedy in important ways, and in the process they gave us wonderfully exuberant films.

Thanks as usual to Kim Hendrickson, Peter Becker, Grant Delin, and their team at Criterion. Thanks as well to Jared Case of George Eastman House for information about their print of Never Weaken.

Lloyd’s autobiography, An American Comedy, was timed to the 1928 release of Speedy, and it’s full of detail about gag structure and the production of his films. At one point he transfers our old friend, the distinction between suspense and surprise, to comedy. The book includes Frances Marion’s memorable line, “Harold, you’ve got to lose your pants.” Coauthored by Wesley Stout, An American Comedy was reprinted in a sturdy Dover edition with a 1966 interview and a cliché-challenging introduction by Richard Griffith.

Lloyd has been lucky in his admirers. Richard Schickel’s Harold Lloyd: The Shape of Laughter (New York Graphic Society, 1974) yields a finely sustained appreciation of his art. Adam Reilly’s Harold Lloyd: The King of Daredevil Comedy (Collier, 1977) is a vast compendium of biography, plot synopses, and visual documentation. Tom Dardis’s Harold Lloyd: The Man on the Clock (Viking, 1973) is a careful biography that situates Lloyd’s career in the development of the film industry. Donald W. McCaffrey offers a comparative study of plot structure in Three Classic Silent Screen Comedies Starring Harold Lloyd (Associated University Presses, 1976).

Most comprehensive of all is the remarkable Harold Lloyd Encyclopedia (McFarland, 2004) by Annette d’Agostino Lloyd (no relation). All the films are synopsized with credits and items from trade papers. Her Harold Lloyd: Magic in a Pair of Horn-Rimmed Glasses (BearManor, 2009) is full of fan enthusiasm, shrewd observation, and information I couldn’t find elsewhere. (She even checked Lloyd’s FBI file.) My Welles quotation above comes from this book, p. 167, as does Harold’s explanation of starting the Boy in one-reelers (pp. 85-86). The indefatigable d’Agostino Lloyd earlier produced Harold Lloyd: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood, 1994).

The Agee essay is of course “Comedy’s Greatest Era” from 1949. My quotations come from James Agee, Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, and Manuscripts, ed. Charles Maland, vol. 5 in The Works of James Agee (University of Tennessee Press, 2017), p. 883. My Chaplin quote comes from Dardis’s biography, page 112. The quotation from Nicholas Kazan is in Jurgen Wolff and Kerry Cox, Top Secrets: Screenwriting (Lone Eagle, 1993), 134. Lloyd’s movie-measuring scheme is explained in P. A. Thomajin, “The Lafograf,” American Cinematographer (April 1928), 36-38, as applied to The Kid Brother, online here. The graph for Speedy is reproduced in Reilly’s Harold Lloyd, pp. 106-107.

A very pretty collection of early Lloyds is on Vimeo from Random Media. The standard DVD assemblage of features and shorts is the multiple-disc Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection. Several of these films are streaming on the Criterion Channel. Unfortunately, the version of Never Weaken (1921) available in these collections is a 1925 re-edit of the original three-reeler. The full version survives, however, and is available, in a so-so video, here. Criterion also offers an excellent Blu-ray disc of Speedy (1928), with solid extras, including an essay by Phillip Lopate and a visual essay on the film’s New York locations by Bruce Goldstein.

I analyze Ozu’s strong debt to Lloyd in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, pp. 152-159.

For the trivia fanatics: I think Harold’s manuscript in Girl Shy is mocking a sensational movie of a few years before, Men Who Have Made Love to Me. This film, written by Mary MacLane, an early feminist and scandal-rouser, was based on her memoirs. The movie is laid out in six parts, each devoted to the seduction method employed by one of her suitors. The film is lost, but it seems likely to have been the target of ridicule in the Lloyd picture.

Girl Shy (1924).

Last Modified: Tuesday | December 19, 2023 @ 20:56  open printable version

open printable version

This entry was posted

on Tuesday | December 19, 2023 at 8:56 pm and is filed under Criterion Channel, Directors: Lloyd, Harold, Film genres, Hollywood: Artistic traditions, Silent film.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.