[Part of Curator’s Corner, a section dedicated to showcasing work of emerging and marginal filmmakers.]

When I remarked earlier this year that South Asia is currently a hotbed of exciting cinematic work, one of the filmmakers I had in mind was 24-year-old Abdul Aziz, an alumnus of Whistling Woods International, Mumbai, who has already three feature films to his credit. A digital native, Aziz’s foray into filmmaking was in the form of short VFX exercises, tongue-in-cheek takes on popular cinema with homemade CGI. Following his graduation in 2019, he set out to make a two-part fictional film exploring romantic relationships across age groups, but as the project took shape, the Chennai-born filmmaker came to the conclusion that it may be better served if each part were a feature in its own right, to which was added a third film. The result was a trilogy of riveting and wholly refreshing works: the Tamil-language Window Flowers (Jannal Pookkal), the Telugu-language Monsoon Breeze (Ruthupavanalu) and the Hindi-language Petals in the Wind (Pankhudiyaan).

Watching the films together, several commonalities surface. All three stories take place over an emotionally eventful evening and culminate at the crack of dawn. They begin indoors, take long detours outdoors and feature extremely low-light sequences illuminated by computer screens or electronic trinkets. Shot quickly over a few days, the films contain no more than two or three characters and typically pivot around a single dramatic revelation, flanked by other events of quotidian drama involving objects such as a plastic bag, a wallet or rose petals. There is a great deal of food banter — preparing meals, discussing menus, talking recipes — but hardly any sight of food. Other subtler crosscurrents unite the trilogy, but Aziz is conscious not to overwhelm individual films with an overarching conceptual design.

Window Flowers (2023, world premiere at International Film Festival Pame, Nepal) begins with a young man (Ajay Serma) knocking at the door of someone who wouldn’t open. After kicking about for a while, he rides back home on his motorcycle to his Mumbai apartment, which he shares with two other men, to spend an evening of disappointment and low-grade heartbreak. Until the funny and spectacular final shot of the film — running for over half an hour — we don’t know what’s eating the young man, but the film works up an inchoate atmosphere of bachelor pad melancholia that is raw and unrelenting. With a bold mid-film excursion into loosely related archival footage, Window Flowers reveals a curious filmmaker working out the poetics of smartphone cinematography — low-light, auto-focus, optical image stabilization, vertical format, long durational — which find fuller expression, formal unity and technical control in Monsoon Breeze.

The second, and in my view the strongest, film in the trilogy, Monsoon Breeze (awaiting world premiere) hits the ground running in setting up scenario of high domestic drama. Deepu (Deepshika Dinapatti) has moved with her mother to Mumbai for her master’s studies. Just when the two prepare to spend an evening shopping, Deepu learns that her estranged father (T.B Naidu) has come home to visit them after nearly a year, right on her parents 25th wedding anniversary. In the cut of the film I saw, this confrontation is staged in a single shot of over an hour, in which we share the father’s barely veiled discomfort in visiting his family, his pretence of normalcy, his forced sense of paternalism, but also his streaks of grace and genuine affection. But the film is centred on the mother, played superbly by Latha Naidu with a reserve, wile and toughness no doubt intimate to Indian viewers but seldom seen on screen.

The strength of Monsoon Breeze lies in the way it plays off an experimental form against a classical dramaturgical outline. The constant threat of the film’s fiction rupturing at any moment, by a stray incident or a technical botch up, is attenuated by the conscious fiction of happy homecoming that the father enacts on his arrival. Among other things, Monsoon Breeze puts a finger on what familial estrangement in an Indian context looks like, every strained moment between father and daughter filled not with uncomfortable silence, but crushingly banal small talk. And when the talk stops, it all comes down like a ton of bricks.

The tension is less familial than sexual in the third film, Petals in the Wind (in post-production), set this time in a tourist-filled Goa. A young couple (Jyotsana Rajpurohit and Dhruv Solanki), dressed like figures in a studio photograph from the 1980s, checks into a secluded guesthouse just after their wedding. They change and go to the beach on a bike, click pictures, take a ride on the giant wheel and return home late without having had anything to eat all afternoon. As they order food online and begin to make love, minor inconveniences snowball into major conflict. Shot (by Devankur Sinha with a digital camera) largely on crowded locations around the beach, the film offers a stark change in scenery from its Mumbai-set predecessors. Crafting a work about the collapse of a honeymoon fantasy, Petals in the Wind offers a perfect midpoint between the romantic frustrations of Window Flowers and the marital disillusionment of Monsoon Breeze.

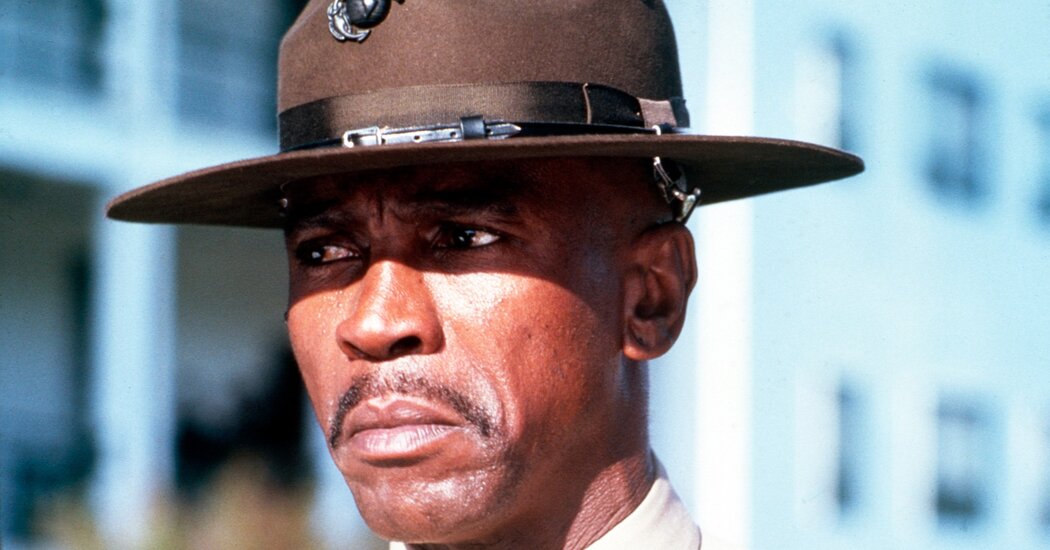

Window Flowers

Monsoon Breeze

Petals in the Wind

Window Flowers and Monsoon Breeze were shot on a smartphone by Aziz himself in real locations and lighting conditions, with live sound and non-professional actors. Although professionally trained, Aziz is inspired by the specific emotional qualities of phone videos. “I would say my usage of the phone camera is more ‘phone’ than ‘camera’,” he remarks, adding that he finds “the emotions evoked by these new-age ‘home videos’ in our phone galleries to be quite a powerful cinematic experience.” The filmmaker had a revelation in college when he revisited a video shot at a party. “I knew everything about the people in it, their relationships and the drama in their lives” he says. Watching the video, he recalls feeling that “there is no film that has ever conveyed more emotional truth than what I’m seeing now.” As a filmmaker, he thought, “you just need to bring your audience to a point where they think I know these people and what’s going on with them.”

There is a pointedly embodied quality to Aziz’s films, both in their hypermobile, handheld cinematography and in the way the films allow viewers to project themselves into their material worlds in an unbroken, video-game like manner. Stylistically speaking, Aziz’s films seem to inhabit an underexplored area of contemporary cinema located between the kind of muscular neo-realism that has become de rigueur in international filmmaking and contemplative slow cinema, dominated by static framing and long shots. Aziz’s work broadly shares with the former a belief in the revelatory aspect of the camera and a tendency to immerse the viewer in a plausible, coherent world resembling ours. At the same time, like slow cinema works, Aziz’s films pay obsessive attention to the minutiae of everyday living, its precise rhythms and its inexhaustibly rich textures.

A lot of this attention develops through exceptionally long shots, often of a labyrinthine choreography, lasting dozens of minutes, that follow the actors from up so close that their features are unflatteringly warped. It isn’t just a question of chaining together stunning long takes — although some of the shots, spanning different apartment complexes and times of the day, are indeed stunning. What gives Aziz’s films their power, I think, is the way they assert the intransigent reality of things taking their own time. These things may be material, like polaroids developing or idlis being prepared over the course of a single shot, or more abstract ones, like the time it takes for the father’s ego to subside in Monsoon Breeze or for the bride to prepare herself mentally for the wedding bed in Petals in the Wind. This insistence on real-time development produces remarkable passages of on-screen poetry, like breaths of a loved one preserved in a balloon.

Then there is the matter of the writing. Aziz’s films are scripted to the last detail, but looking at them, it is hard to believe that they weren’t entirely improvised. What stand out are the filmmaker’s ear for the essential bizarreness of quotidian chatter, his attention to moments that seem so random that they could only have come from real life and the employment of props that are remarkably uncinematic. The persistent mundanity of the dialogue, always compelling but divested of the need to reveal character or impress the audience, isn’t the kind of slick, anti-climactic patter you find, say, in Tarantino’s films. It rather elevates the ordinariness of everyday speech, rendering it interesting in a manner that traditional movie scripts refuse to.

All this turns Aziz’s films into a kind of vernacular urban ethnography that documents the behaviour, body language and mores of a specific social stratum with a precision and candour that is bracing. There is nothing crowd-pleasing about these films, little concession to character types and a whole lot of faith in the audience. In their internal variations, Aziz’s three films become testimonies to the filmmaker’s evolving ideas about screen realism, its limits and its relationship to higher truths. Embracing mistakes and refusing surface polish, they constitute an imperfect, rough-edged cinema that broaches the formal taboos of industrial and academic filmmaking. I can’t wait for the world to discover these films, vivid and throbbing with life.

If you are a critic or a programmer wishing to see these films, please reach out to Aziz at the address below.

Bio

Abdul Aziz is a 24-year-old filmmaker from Chennai, Tamil Nadu, based in Mumbai. He passed out of Whistling Woods International (specialized in film direction) in 2019. He was awarded at the 52nd International Film Festival of India (IFFI) in the first edition of their Creative Mind of Tomorrow program for his diploma film Tulips. He has written and directed three independent feature films Window Flowers, Monsoon Breeze and Petals in the Wind. He has also co-written a commercial black comedy starring Swastika Mukherji titled Dead Dead Full Dead and an indie road movie titled Blah Blah Blah.

Contact

abuthoaziz@gmail.com | Instagram | Twitter

Filmography

- Tulips, 2019, 18 min., digital

- Trees and Their Loved Ones, 2022, 30 min., digital

- Jannal Pookal (Window Flowers), 2023, 105 min., digital

- Ruthupavanalu (Monsoon Breeze), 2024, 120 min., digital

- Pankhudiyaan (Petals in the Wind), 2024, 103 min., digital

- Writer, Dead Dead Full Dead (dir. Pratul Gaikwad), 2024

- Writer, Blah Blah Blah (dir. Dhruv Solanki), 2024

Showcase

Trailer for Window Flowers (2023), password: WF

Trailer for Monsoon Breeze (2024), password: MB