Rick Surowicz

Quiet fallen snow blanketing a field and farmhouse is an inviting subject, but don’t overlook opportunities to have fun exploring winter up close. A vine-wrapped fence post or the scrub along a frozen creek can be exciting, too. These subjects provide a chance to zoom in and let nature’s textures shine. Because I like to work with watercolor transparently, I must carefully plan to preserve my light-valued textures.

Jessica L. Bryant

The subtle nuances of snow can be deceptive, so I’m careful not to trust a quick glance while painting. It’s important to see accurately and not unintentionally deviate from the reference. I find that it enhances my odds for capturing mood and atmosphere when I take the time to really look and understand the nature of the shapes, values and transitions/edges. This includes knowing what shape each value makes before shifting into another value shape and recognizing the nature of the transition (whether abrupt or gradual). Capturing those subtle value changes can really help the snow come to life.

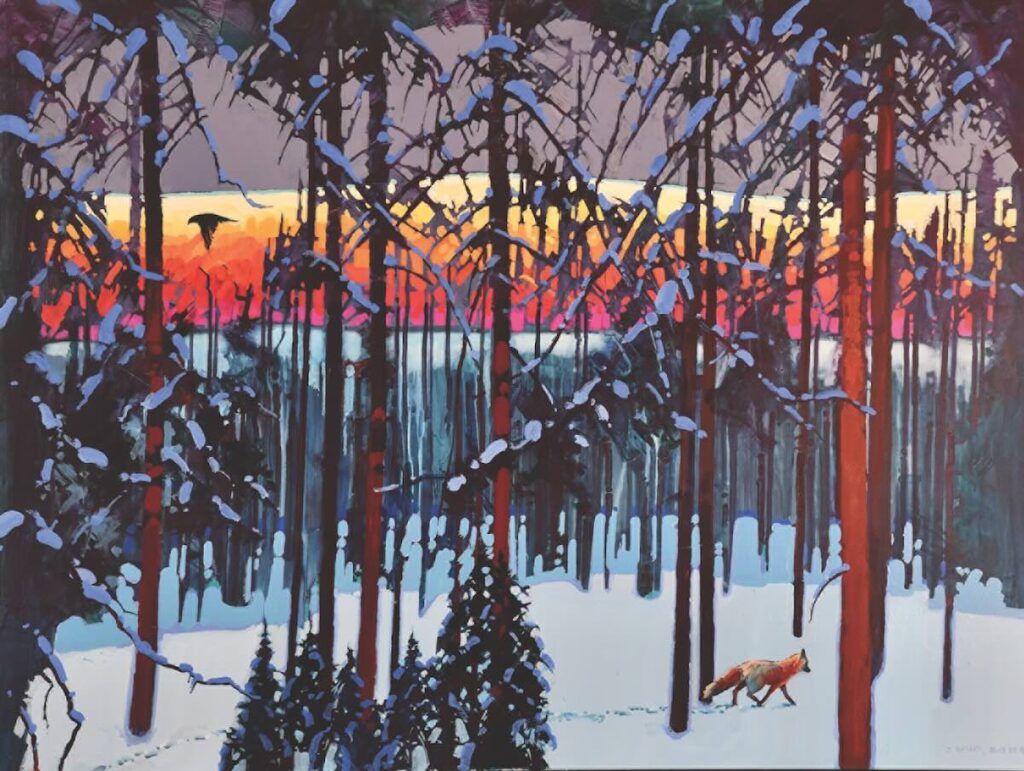

Stephen Quiller

A coating of snow simplifies the landscape. By removing much of the detail that many painters struggle with, it makes it easier to see a scene abstractly. When painting snow, tune your eye to see the variety of color, which changes along with the atmospheric conditions and the time of day. In strong diagonal light, with an indentation in the snow—like the tracks of animals or cross-country skis—look for what’s called retreating light (the light as it moves away from the sun), highlight (where the sun directly hits the angle of the snow), retreating shadow (as the snow moves into the indentation) and the depth of shadow (at the darkest and deepest part of the indentation).

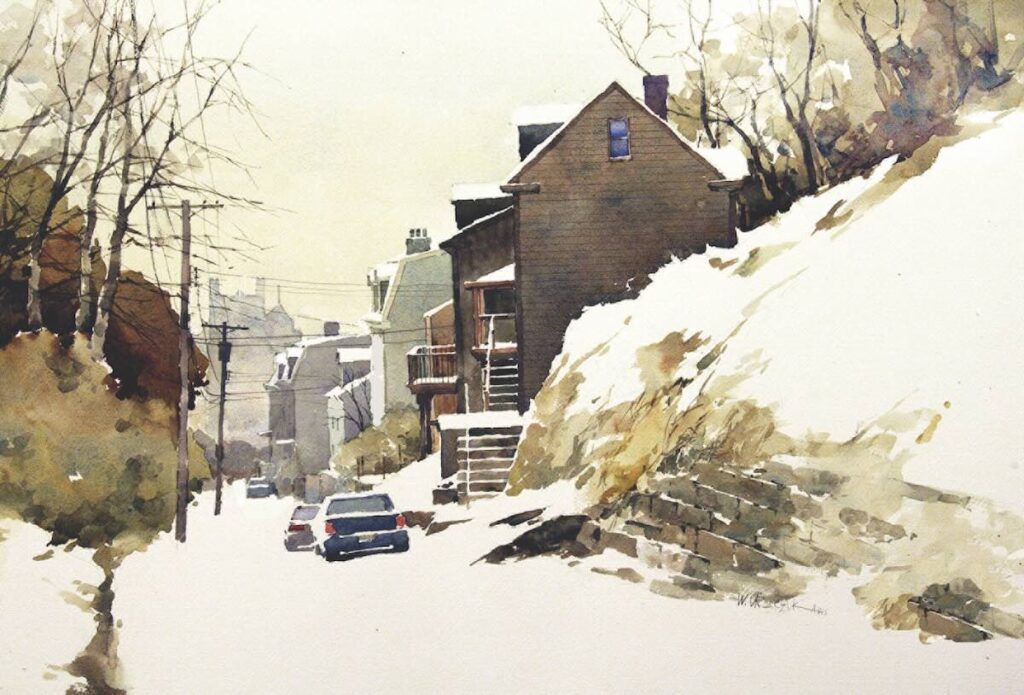

Bill Vrscak

For me, it’s the power of pure white paper in a watercolor. I’m an inner-city boy, and I like to paint the urban scene. When painting winter in the city, I often take a graphic approach. I organize my composition to surround the subject matter with flat white shapes that represent snow. I try to avoid breaking up those larger shapes too much, because they serve two functions: Pictorially, they represent what the painting is about—winter. At the same time, they serve graphically as containment devices that surround the subject matter and lead the viewer through the important parts of the painting. It may be less photorealistic but can be very effective.

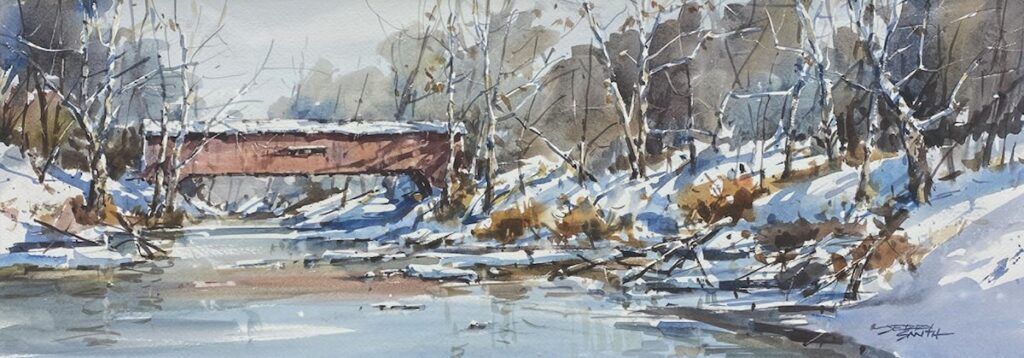

Jerry Smith

Snow scenes are spectacular in all phases of nature, from gray and subdued to dazzling bright. Snow, as a form of water, has the potential of being well-represented in watercolor. Regardless of style, snow must appear cold and wet in a painting to appear believable. With this in mind, top considerations include: the need for a balance of soft and hard edges; an awareness that all the colors in the spectrum are contained in snow; and an effective use of highlights and shadows to direct movement toward the composition’s focal point.

Brienne M. Brown

Remember that snow is not white. There are many colors in the light and shadow shapes. I always tint the white areas either warm or cool, so I can create form and depth with color temperature shifts. This is useful no matter the medium. When painting in oil, I never use titanium white straight from the tube; I tint the paint with small dabs of color. When working in watercolor, tinting the white paper has the same effect. I start by painting shadows, but go back afterward with a glaze to tint the remaining white.

Enjoying this article? Sign up for our newsletter!