Does form carry associations of gender? Does material? In both cases, yes and maybe. Even abstract forms can contain markers of gender (though archaeology reminds us how these shift over time). Humans are good at pattern recognition; pareidolia – the tendency to find images or meanings in random shapes – comes naturally to us. We can ‘see’ faces and body parts in objects animal, mineral or vegetable. As to whether there are abstract forms that might unconsciously betray the gender of their maker? That is quite a different question, and one that is teased by the exhibition ‘Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction’ – a sculpture-centric show of work made between 1950 and 1970, in which all the artists happen to be women.

Chain (c. 1963–71), Claire Falkenstein. Photo: Fraser Marr; courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York. © The Falkenstein Foundation; courtesy the Levett Collection

The question of whether materials carry associations of gender is no less vexed. There are craft-associated media that carry the whiff of the kitchen (metaphorically, and sometimes actually) and small-scale making at the centre of a busy home. Soft stuff like quilts and woven textiles. In Eastern Europe, there were other reasons to turn to fibre art in the middle of the 20th century: if avant-garde art could masquerade as craft, it was less likely to attract censorship. The exhibition’s handsome opening display centres on the Polish artist Maria Teresa Chojnacka’s Lancuchy (‘Chains’) (1973) – three great cascades of hand-knotted sisal links that puddle on the floor, awaiting a subject to restrain.

More is made at a kitchen table than crochet and quilts: one such here is a colonic metal monster shown hanging from the ceiling, as it once hung above Marisa Merz’s dining table when she wasn’t working on it. Untitled (Living Sculpture) (1966) looks like flaccid industrial pipes but was coiled and stapled together from thin sheets of aluminium when Merz got the time between chores. Like a cooker hood attracting grease, there are apparently sections of the work still sticky with airborne oil from the Merz family kitchen.

Marisa Merz with Living Sculptures, Turin, 1966. Photo: Renato Rinaldi; © SIAE; courtesy Archivio Merz/Marisa Merz

She was not the only artist favouring materials with a macho heft. Louise Nevelson gathered scrap wood from the New York streets, then hauled them to her studio to piece into assemblages at an architectural scale. Painted in gold, Royal Tide III (1961) looks like some kind of mysterious machine, yielding its secrets to no one.

Royal Tide III (1961), Louise Nevelson. Private Collection, London; © ARS, NY and DACS London 2023

Others favoured new materials, free from the boys’-club associations carried by bronze and marble. Lynda Benglis poured a disobedient excremental pile of black polyurethane foam into the corner for Untitled (Köln) (c. 1970). Carla Accardi painted on to clear plastic film, so that her brushstrokes sat suspended in the air in front of the wooden stretcher.

Grigionero (1972), Carla Accardi. © Archivio Accardi Sanfilippo; courtesy Arianna/ArtTotal

The two decades covered by ‘Beyond Form’ overlap with the early years of the women’s movement, a period during which politically progressive female artists started to feel that the cloak of (relative) gender invisibility afforded by abstraction was actually a trap. Representation was going to be key to the feminist project. Many of the artists are already flirting with figuration – and more. Hannah Wilke’s Five Androgynous and Vaginal Sculptures (1960–61) are little terracotta boxes like Egyptian votaries, the hollow interior of each one viewed through an unmistakably labial opening. Carved into the limestone of a stalactite – new stone freshly born in the womb of the earth – Mona Saudi’s Motherhood (1972) is a maternal form reduced to a geometric symbol, at once ancient and modern.

Wilke, Saudi and Eva Hesse were thinking about ways to engage with the female body while swerving five centuries of art history. Coming in through abstract forms, through engagement with materials, seemed a good route. While it is not the latest work within this exhibition’s span, in spirit ‘Beyond Form’ bows out with Hesse’s Addendum (1967) – a row of small domes sprouting from a board and spewing trails of cord, all in a dead, dirty grey. Despite foregrounding its own artifice, its seriality, its abstract sensibility, it is still hard not to see breasts, nipples, milk. You have to go a very long way beyond human form for the human brain to resist pulling you back to it.

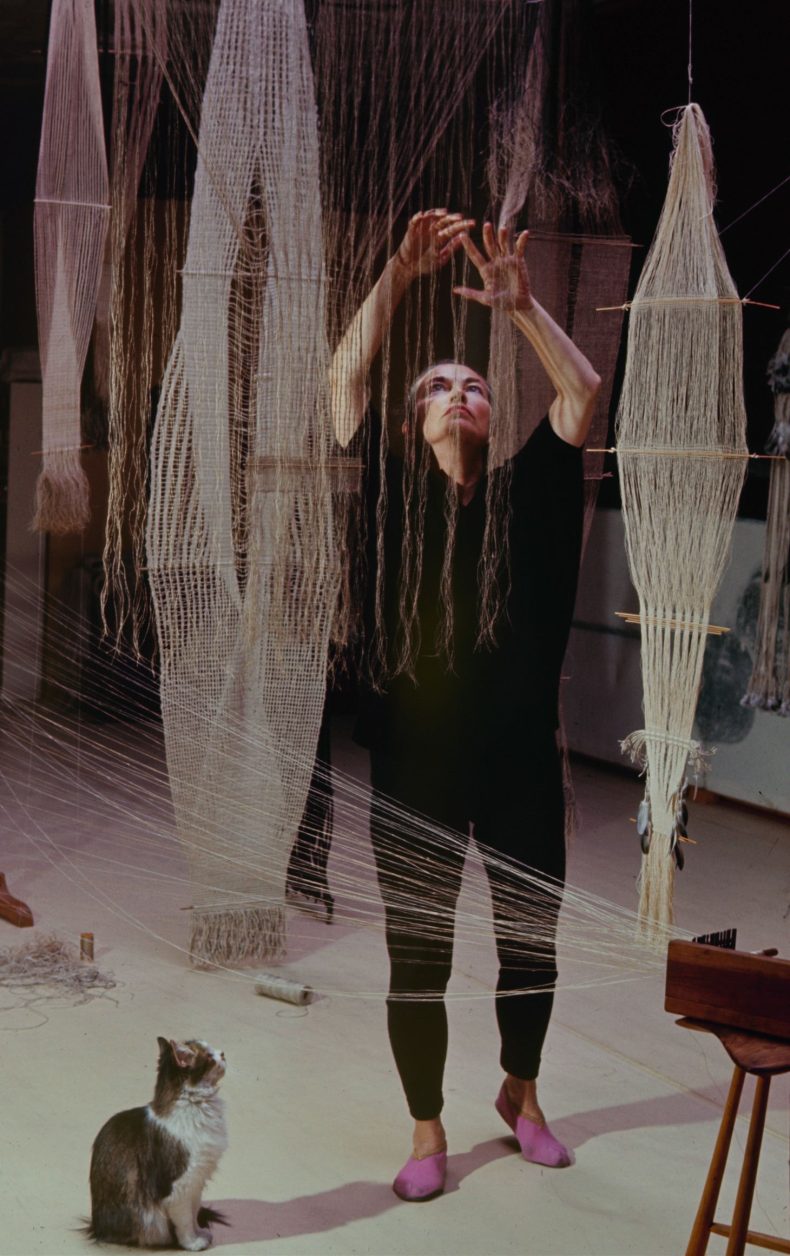

Lenore Tawney at work, New York, 1966. Photo: Nina Leen/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

‘Beyond Form: Lines of Abstraction 1950-1970’ is at Turner Contemporary in Margate until 6 May.