This time last year, headlines were dominated by the bewilderment at the draconian funding cuts imposed on opera companies and ensembles by a seemingly heedless Arts Council England. A year later, much of that bewilderment remains, and in some ways has only increased, while the consequences of those cuts are still emerging.

The Manchester-based new-music group Psappha has disbanded, while the future of Leeds Lieder was called into question, in both cases as a result of the withdrawal of their grants, and even though both were organisations that appeared to meet all ACE’s criteria for regionality and “levelling up”.

Meanwhile it was announced that from next year the Cheltenham music festival, one of the longest established in the UK, would be a pale shadow of its former self. Since then, too, Creative Scotland and the Arts Council of Wales have emulated their English counterpart by withdrawing funding from the Lammermuir festival and Mid Wales Opera respectively, the first a much valued autumn oasis of high-class music making, the second an imaginative, small-scale touring company committed to taking opera to those parts of Wales and its borders that no other company can reach.

Uncertainty over the future of ACE’s most prominent victim, English National Opera, continued. The year ends with the company shorn of its music director, Martyn Brabbins, who resigned when plans to reduce the orchestra significantly were made public.

Since the plans for ENO’s enforced move out of London were finally announced confusion and anger have only intensified: it seems that the company’s new base in Manchester will bring only smaller-scale work to the city, and that full-scale productions will continue to be staged each year at the Coliseum in London in a four- or five-month season, more or less what it is doing at present. In addition, there is still no mention of the company touring its stagings, a move that might finally justify its “national” epithet.

As for the opera that did reach the stage in the current year, productions of Wagner’s Das Rheingold, presented at ENO in February and Covent Garden in September, led the way, the first, directed by Richard Jones to a generally mixed reception, the second, staged by Barrie Kosky, regarded as a promising start to the Royal Opera’s new cycle. Otherwise at the Coliseum there was artistic director Annilese Miskimmon’s own staging of Korngold’s The Dead City, superbly conducted by Kirill Karabits, and a revival of David Alden’s brilliant 2009 production of Britten’s Peter Grimes as a sharp reminder of much happier times, while the Royal Opera gave new versions of Berg’s Wozzeck, directed by Deborah Warner, with Christian Gerhaher compelling in the title role, and Verdi’s Il Trovatore, vividly presented by Adele Thomas.

Covent Garden also presented three of the most striking new works. Whatever its dramatic shortcomings, Kaija Saariaho’s Innocence offered an orchestral score of characteristic luminosity, but was an occasion remembered with sadness, as the death of the composer was announced a few weeks later. The slender, fairytale simplicity of George Benjamin’s Picture a day like this was matched to music in which not a note or an instrumental colour was out of place, while Brian Irvine’s moving depiction of the story of Rosemary Kennedy, Least Like the Other, was brought to the Linbury theatre in London by Irish National Opera. Aldeburgh festival opened with a strikingly imaginative operatic premiere too – Sarah Angliss’s Giant (coming to the Linbury next year) – while the highlight of the year at Welsh National Opera (another company ending the year without a permanent chief), was the production of Osvaldo Golijov’s Ainadamar, previously seen in Scotland.

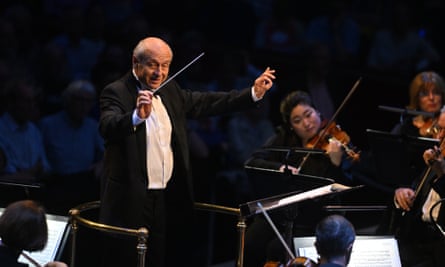

Orchestras seized on the 150th anniversary of Rachmaninov’s birth as an opportunity to overdose on his symphonies and concertos, while the year’s other significant anniversary, the 400th of the death of William Byrd, was also widely if more quietly celebrated. The BBC Proms predictably made a lot of Rachmaninov, rather less of Byrd. However, it was performances of Mahler, especially Simon Rattle’s account of the Ninth Symphony in his final British concert as the London Symphony Orchestra’s chief conductor, and the Aurora Orchestra’s remarkable performance from memory of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in a slickly presented theatrical package, that were among the most memorable evenings – together with the UK premiere in a semi-staging of György Kurtág’s Endgame and the weekend of concerts by Iván Fischer and his Budapest Festival Orchestra. All this in a year in which other great European orchestras were conspicuous by their absence at the Albert Hall.

Conductor Klaus Mäkelä was among the international visitors to the Proms, alongside pianist Yuja Wang, as dazzling in Rachmaninov’s Paganini Rhapsody as she had been earlier in the year with the LSO in the UK premiere of the concerto Magnus Lindberg had composed for her.

Wang and Mäkelä – this time with his Oslo Philharmonic – also visited the Edinburgh international festival, which under the artistic leadership of Nicola Benedetti this year began to show signs of returning to its former stature. In London, the Southbank Centre, once the hub of the capital’s musical life, continued its slow decline. Occasional concerts, such as the UK premiere of Heiner Goebbels’ A House of Call, and the Ligeti 100th anniversary celebrations, were a reminder of the kind of special events that used to be a regular part of the Southbank’s programme, but concerts of real note there were otherwise sparse.

Truly outstanding piano recitals were few and far between, too, but Steven Osborne’s evening of Rachmaninov at the Wigmore Hall, Emanuel Ax’s Schubert and Liszt at the Chipping Campden festival and Vikingur Ólafsson’s London recital (at the Royal Festival Hall) in his international tour promoting his CD release of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, would have stood out in any year.

The huge success of Ólafsson’s Bach disc was perhaps the most remarkable feature of the year’s classical releases. A year ago, the recording industry was still recovering from the impact of Covid, and the inevitable constraints it had put on new projects, whether studio- or concert-based. Those knock-on effects have now all but disappeared, though the shape and emphases of the industry have shifted, almost certainly for ever. Studio recordings of large-scale works have become vanishingly rare.

What has shifted, too, is listeners’ reliance on CDs, with an increasing share of the market now given over to digital downloads. Though the fraction of recordings released exclusively as downloads is still relatively small, the emergence of Apple’s Music’s Classical app, offering high-quality streams of an impressively high proportion of the catalogue significantly enhanced by Hyperion’s decision to finally make its works streamable, has surely accelerated the move towards disc-free listening.

The ecology of classical music and opera in Britain may still be fragile, but there are still things to enjoy and even reasons to be optimistic, if you look hard enough.