In the spring of 1825, Ludwig van Beethoven was struck by a gut ailment so severe that he thought he might die. That summer, after he recovered, he returned to the string quartet he’d been writing before his illness—Quartet No. 15 in A Minor, Op. 132—and added a new segment inspired by his survival. To this day, the piece is known for the slowly unfolding, baffled joy of its third movement, where the music seems to trace the shuffling steps of an invalid breathing fresh air for the first time in weeks. Beethoven would call it Heiliger Dankgesang, a “holy song of thanksgiving.”

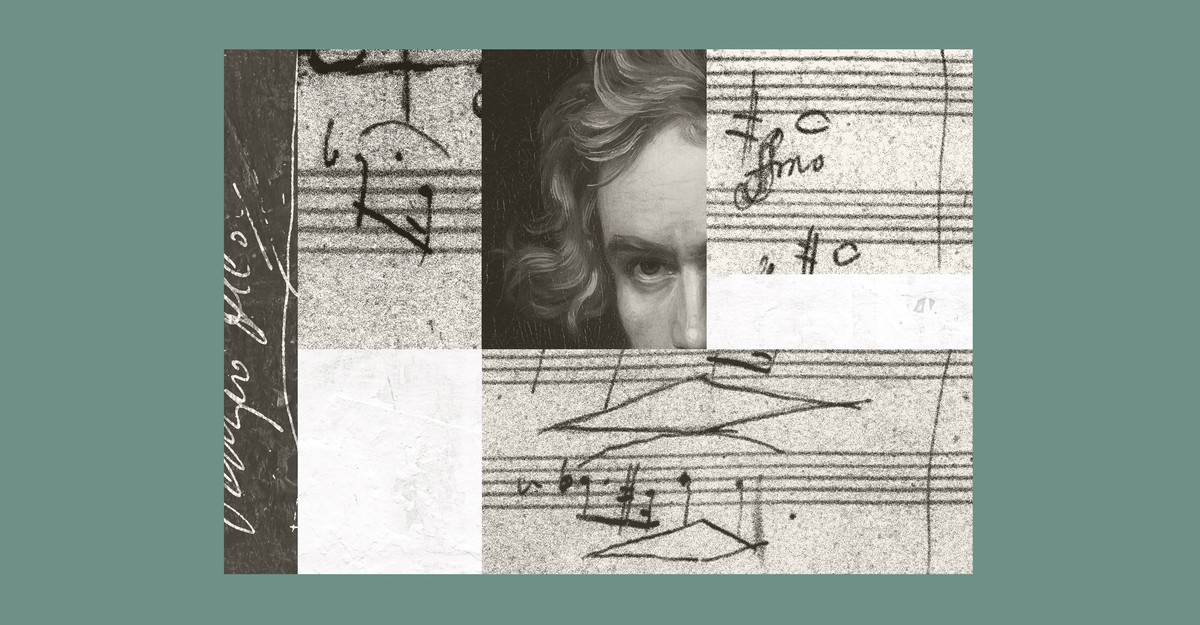

He wrote in the mornings when the light was good, on rag paper thick enough that he could scrape off mistakes with a knife. His handwriting was notoriously chaotic: He couldn’t draw a set of parallel lines if his life depended on it. The maestro is said to have used his pencil not only to write with, but also to feel the vibrations of his piano, pressing one end of the wooden rod to the instrument while holding the other end between his teeth. He was by now profoundly deaf; in less than two years, he would be dead.

Once he finished a composition, Beethoven would hand off the manuscript to a copyist, who’d write it all out again, this time legibly. After Beethoven corrected any mistakes the copyist made—berating the man the whole time—the score would go to a publishing house where, after more last-minute changes from the composer, an engraver would trace it, backwards, onto a copper sheet. From there, the score would be published and republished, appearing in largely the same form on music stands across the world even to this day.

But even discounting those final revisions, the Opus 132 that the world came to know was not exactly the Opus 132 that Beethoven handed to his copyist. The composer littered his original score with unusual markings that the copyist simply ignored. Below one staff, for example, Beethoven jotted “ffmo”—a tag that wasn’t a standard part of musical notation, and wasn’t used by any other major composer. In another place, he drew an odd shape like an elongated diamond, also a nonstandard notation. None of these marks made it into even the first clean copy, let alone the published version. Almost no one would see those marks in the roughly 200 years after Beethoven first scribbled them down.

Then, one evening in 2013, the violinist Nicholas Kitchen was in New Mexico coaching a quartet through Opus 132. Kitchen is a man of obsessions; one of them is playing from a composer’s original handwritten manuscripts, rather than printed music, so he had a facsimile edition on hand. The errant “ffmo” caught the eye of the quartet’s cellist. “What’s this?” she asked.

As soon as Kitchen saw Beethoven’s mark, something in his brain shifted; later, he would tell people that it was as if someone had turned over a deck of cards to reveal the hidden faces behind the plain backs. Suddenly, he had a new obsession. Over the next several years, he would come to believe he had discovered Beethoven’s secret code.

For most of the past two centuries, Beethoven’s original handwritten manuscripts have been difficult, if not impossible, for musicians to access. Few could afford a trip to view them at archives in Vienna or Berlin, and facsimile editions were prohibitively expensive. Scholars hadn’t bothered taking a look: By the time musicology arose as a discipline, Beethoven was seen as passé, says Lewis Lockwood, a Harvard professor emeritus and co-director of the Boston University Center for Beethoven Research. “There is no army of Beethoven scholars,” Lockwood told me. “It’s a tiny field … terra incognita.”

Kitchen is not a scholar. A boyish 57-year-old with a shock of bushy white hair, he’s a working musician and a faculty member at New England Conservatory, where my parents also taught. The Boston classical-music world is a small one—almost everyone I interviewed for this story is friendly with my violist mother and pianist father—and Kitchen is well known and well respected in those circles. Prior to reporting this story, I’d heard him perform with his quartet many times, although I didn’t know him personally.

That said, I was aware that Kitchen had a bit of a reputation as, if not an eccentric, at least an enthusiastic innovator. Around 2007 he persuaded the ensemble he co-founded, the Borromeo Quartet, to play from full scores instead of parts, because he felt it enriched the performance. A full score doesn’t fit on a music stand, so the group was among the first to play from laptops, and later iPads, in performance.

Around the same time, scans of Beethoven manuscripts began to appear on a wiki site for musicians called the International Music Score Library Project. The only thing better than playing from a full score, Kitchen believed, was playing from a handwritten original full score—the closest glimpse possible of the composer’s working mind. “Just by reading the manuscript, you are instantly exposed to an archaeology of ideas,” Kitchen told me. “You’re tracing what was crossed out—an option tried and not used, one tried and refused, then brought back—all these processes that are instantly visible.”

The more Kitchen played directly from Beethoven’s chaotic handwriting, the more anomalous notations he found. Initially, Kitchen didn’t know what to make of them. “My first thought was, ‘Well, it may be the equivalent of a doodle,’” he said. But once he began to study Beethoven’s scores more systematically, he realized just how prevalent—and how consistent—many of these strange markings were across the composer’s 25 years of work.

Kitchen began to develop a theory about what he was seeing. The marks mostly seemed to concern intensity. Some appeared to indicate extra forcefulness: Beethoven used the standard f and ff for forte, “loud,” and fortissimo, “very loud,” but also sometimes wrote ffmo or fff. He occasionally underlined the standard p or pp for piano and pianissimo, “soft” and “very soft,” as if emphasizing them.

Whenever people have tried to invent a way of writing music down, the solution has been imperfect. Jewish, Vedic, Buddhist, and Christian traditions all searched for ways to keep sacred melodies from mutating over time; each ended up inventing a set of symbols for different musical phrases, which worked as long as you already knew all the phrases. Other cultures evolved away from notation. In classical Indian music, for example, every soloist’s performance is meant to be improvised and unrepeatable.

In Europe, however, musical values began to emphasize not spontaneity but polyphony: ever more complex harmony and counterpoint performed by ever larger ensembles. For these ensembles to play together, they needed some kind of visual graph to coordinate who plays what when. The result evolved into the notation system in global use today—an extraordinarily lossless information-compression technology, unique in its capacity to precisely record even music that has never been played, only imagined. Orchestras in Beethoven’s time, as well as now, needed only the score to play something remarkably similar to what the composer heard in their mind. It’s as close as humans have come, perhaps, to telepathy.

By Beethoven’s time, composers had developed ways to communicate not just pitch, duration, and tempo, but the emotion they wanted their music to evoke. Dynamic markings shaped like hairpins indicated when the music should swell and when it should ebb. A corpus of Italian words such as andante, dolce, and vivace became technical terms to guide the musician’s performance. The effect was a lot like the old religious systems: If you already knew how andante was supposed to sound, then you knew how to play something marked andante. But compared with the rest of the notation system, such descriptions are subjective. How passionate is appassionato, exactly?

Someone like Beethoven, a man of extreme moods, might very well have chafed against these restraints. It’s not a stretch to conclude, as Kitchen has, that Beethoven would feel the need to invent a method of more perfectly conveying how he intended his music to be played.

But whether Kitchen is correct remains up for debate. Jonathan Del Mar, a Beethoven scholar who has worked extensively with the composer’s manuscripts, told me in an email that any anomalous marks in Beethoven’s manuscripts were merely “cosmetic variants” of standard notations. Beethoven was a stickler for precision, Del Mar explained, especially when it came to his music, and if he’d cared about these marks, he would have made sure they appeared in the published versions. “I am absolutely convinced that, indeed, no difference of meaning was intended,” Del Mar wrote.

Jeremy Yudkin, Lockwood’s co-director at the Center for Beethoven Studies, also initially viewed Kitchen with skepticism. “When I first talked to him, I thought he was nuts,” Yudkin told me. But Kitchen’s close and careful research won him over. Yudkin now believes that Kitchen has discovered a previously unknown layer of meaning in Beethoven’s manuscripts: “There are gradations of expression, a vast spectrum of expression, that music scholars and performers ought to take into account,” he said.

As to why the marks never made it into the composer’s printed scores, Yudkin thinks Beethoven may have accepted that his large personal vocabulary of symbols and abbreviations wouldn’t be easily deciphered by others. Perhaps, Yudkin suggested, he included the marks in his manuscripts simply for his own satisfaction. “You put things in a diary,” Yudkin said, because it yields “a mental satisfaction and emotional satisfaction in being able to express what it is that you feel. And no one else has to see it.”

Over the past few years, Kitchen and the Borromeo Quartet have presented a series of Beethoven concerts prefaced by brief lectures on his findings, but other than that, and his presentations at BU, he hasn’t spent much time sharing his ideas with the world. Instead, he’s been preparing his own set of Beethoven scores that will include all the marks left out of earlier editions. He wants other musicians to be able to see them easily, without needing to decipher Beethoven’s scrawl. “And then,” he said, “people can argue about all those things as much as they want.”

As I was working on this story, I asked my father, the pianist, why he thought Western notation had developed to such specificity, even before Beethoven’s time. He told me he thought it was because of a change in composers’ perspective: Where before they’d been composing anonymously for the Church, as music became more secular, composers’ names became more prominent. “They started to think about how people would play their work after their deaths,” he said.

For Kitchen, that’s precisely the point of studying Beethoven’s markings. If written notation can encode music, he told me, music can encode human feelings. Therefore, written music can actually transplant “a living emotion” from one mind to another. It’s not just telepathy: Music allows a sliver of immortality.

At this point, Kitchen believes he knows the code well enough that he can hear it in music. Once, at a concert in Hong Kong, he was listening to a performance of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 23 in F Minor, Op. 57—the “Appassionata.” He noticed an unstable chord that seemed especially ominous and unsettling—the kind of quiet but emotionally powerful moment that Beethoven often noted with one of his bespoke abbreviations.

“I said, ‘I bet you that’s a two-line pianissimo,’” Kitchen recalled. After the performance, he checked. Sure enough: Scrawled below the disconcerting bass note troubling the otherwise serene chord, Beethoven had written a double-underlined pp. Two hundred years later, maybe Kitchen finally understood exactly what he’d meant.