Have you ever wondered why they call it the long 19th century? From Beethoven’s hammering martellatos, to Wagner’s massive, veiny works that seem to last forever, to Liszt’s immense hand size (…), the Romantic period was in many ways a musical virility contest with many—many—climaxes. But there was one composer who critics considered the most virile of them all. We know this because almost every review of her work comments first and foremost on its virility. That composer is Augusta Holmès.

If you haven’t heard of Augusta Holmès, a French composer of Irish descent, her virility may in fact be why. As with all women composers of her era, Holmès’s music was evaluated more as a gender performance than a musical one. “The most surprising thing about her musical talent is its completely virile quality,” the poet Auguste Villiers de L’Isle-Adam enthused. “Her music has a vigor, a virility, an enthusiasm, which deserve better than the banal praise usually bestowed on female composers,” added La Liberté. By 1900, however, Holmès’s fame, sexual freedom, and toned brass chorales began to work against her. “This music gives me the impression of being transvestite,” a Le Courrier Musical critic wrote that year. “Oh, Ladies, be mothers, be lovers, be virgins…but don’t try to be men. You will not succeed in replacing us, not entirely.” After her death, her music was rarely heard again.

But it was too late. The throbbingly virile works of Augusta Holmès had already proved that virility, like artistic merit, has no gender. “I have the soul of a man in the body of a woman,” Holmès once declared. Born in Versailles in 1847, the composer was raised in the company of her Irish military father’s mounted weapons, as if to prepare her for the battle of being a woman composer in Third Republic France. Primarily self-taught (women were barred from the Paris Conservatory), she was anointed by the infamously virile Wagner and Liszt, and lusted after by the less-virile-but-trying Saint-Saëns, Gounod, Massenet, Franck, D’Indy, and more. A composer of art songs as much as large-scale works, I don’t even need to tell you that she wrote her own texts.

Holmès’s virile lifestyle, as much as her works, put Ernest Hemingway’s to shame. Between having four to five children in an affair (the numbers are hazy because she lived alone in her own Parisian bachelor pad), joining the ambulance corps during the Franco-Prussian War, and posing nude for oil paintings, she also composed. Late in life, she studied with César Franck, who wrote his near-pornographic Piano Quintet for her, to the chagrin of his wife. A dual-national nationalist who spoke five languages, Holmès composed jingoist banger after banger for France, Ireland, Poland, and Italy. As Saint-Saëns put it: “She was powerful—maybe too powerful.”

What was the most virile composer’s most virile work? There is no single metric for virility in classical music, but I have attempted to create this ranking through an intensive process involving cold showers, Schenkerian analysis, and CrossFit. Musical factors included how extended is the duration, how pounding is the fortissimo, how forward-thrusting is the tempo, how imposing is the number of players onstage, how intellectually unfathomable is the form, how fawning is the reception, and how long is the hair. Try these Romantic works on for size and see if you, too, aren’t surging with potent ideas, dominating your rivals, and generally inseminating the world with your presence.

15. “Trois anges sont venus ce soir” (1887)

This is arguably Holmes’s biggest hit, but there’s not much that’s virile about Christmas. An immaculate conception? Virility score: 3/10.

14. “La Montagne Noire” (1895)

“La Montagne Noire” was the first opera by a woman to be staged at the Paris Opera (virile), but had a short run, likely due to its Wagnerian leanings (virile) and being way too long (virile). Listeners should be warned that the lead soprano’s vocal and sexual power is not punished with death in this opera. Not only does she get her man and her money, she exits the stage entirely unscathed by misfortune.

Holmès was not as lucky. “We do not want to open the doors of our theatres and opera-houses to women writers and composers,” one reviewer wrote. Franck biographer Laurence Davies said of the opera: “It was Augusta’s faiblesse that she could not resist the temptation to write virile, explosive sounds, such as no other woman composer would have dared to make.”

“They have tied me to a stake and pelted me with arrows and mud,” she told Saint-Saëns afterwards in a letter. (Not unlike fellow virile queen, Joan of Arc.) Virility score: 5/10

13. “Les Argonautes” (1880)

One critic panned this piece for its “excessive virility—a frequent fault with women composers.” Another, however, praised that there was “nothing of the feminine about it.”

Virility score: 5/10; “excessive virility” is gauche unless you’re a Germanic composer whose last name starts with “B.”

12. “Astarté” (1871)

Liszt weighs in: “In comparison to your ‘Astarté,’ the works of the most daring composers are no more than little pieces from a girl’s boarding school.”

Virility score: 6/10; unpublished, thus un-virile.

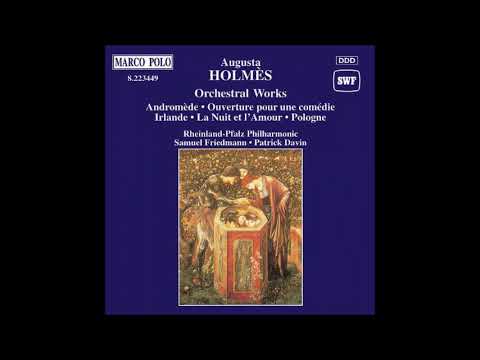

11. “Ouverture pour une comédie” (1870)

It was notoriously difficult for women to corral enough support to get their operas staged (see Leah Broad’s group biography, Quartet: How Four Women Changed the Musical World). To overcome this hero’s trial, Holmès devised the stratagem of performing her overtures like singles before the album. Pure, uncut virile ingenuity.

Unfortunately, this early work was never published, and the harp here is used angelically, not furiously. Virility score: 6/10.

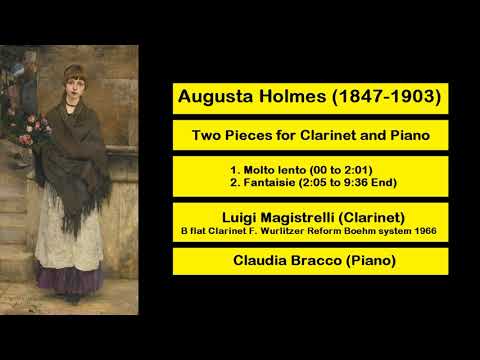

10. “Molto lento” and “Fantaisie in C minor” for Clarinet and Piano (1900)

Holmès had a special preference for this long, wooden instrument and even played it herself (yes she did). The “Molto lento” is titillating, but we all came here to hear Holmes`s steamy “Fantaisie.” (A personal favorite—very vivid.)

Virility score: 7.5/10; only one player.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Processing…

Success! You’re on the list.

Whoops! There was an error and we couldn’t process your subscription. Please reload the page and try again.

9. “Le ruban rose” (1899)

In this fecund little art song, one of over 100 that Holmès both composed and wrote (virile), a marquise bones her page in the woods. When a passing prince wants to join the action, chaos ensues. 7.5/10

8. “La princesse sans coeur” (1889)

The only thing more virile than a princess without a heart is the way this song teeters on the brink of chromatic apocalypse before nonchalantly going back to seducing the listener. 7.5/10

7. “La guerrière” (1892)

Holmès was known for her inhuman vocal range, which this dramatic ode to a slain woman warrior flaunts. The song ends with a liquid dissonant surprise, but could have been more formally unfathomable. The moral of the story is never trust your brother. Virility score: 7.5/10.

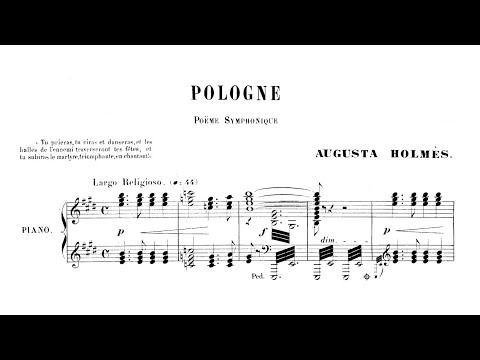

6. “Pologne” (1883)

This symphonic poem is gloriously martial, building to a graphic musical battle inspired by an 1861 Polish political uprising that ended in a massacre by the Russians. The epigraph on the score reads in French: “You’ll pray, you’ll laugh, you’ll dance, and the enemy’s bullets will cross your feasts. You’ll suffer martyrdom, triumphant in song.” Did I mention that Holmès was a Sagittarius?

“Pologne” goes out to everyone resisting their political oppressors. I find the piece best enjoyed blasted from the subwoofers of a 1000 horsepower Exorcist Camaro. Virility score: 8.5/10

5. “Ludus pro patria” (1888)

“There reigns in this work a virile and powerful spirit that is astonishing in a woman. And, so that my meaning is not misunderstood: It is not a matter here of the imitation virility that, too often, women affect in their artistic productions.”—Le Figaro. Virility score: 8.5/10.

4. “Rolande furieux” (1867)

Holmès’s virility has two main modes: the heroic and the sensual. “Rolande Furieux” is a rich paleo feast of both. Based on Ludovico Ariosto’s 16th century epic poem Orlando Furioso, this symphonic adventure tone-paints many essential virile experiences: lovemaking in the woods, galloping long distances by horseback, and flying into a jealous rage so frenzied that you soar to the moon. Once, while listening, I was moved to accidentally walk up an extra flight of stairs. Virility score: 8.5/10.

3. “Irlande” (1882)

Each of these pieces has, of course, been tested for use while weightlifting. I find that “Irlande” is ideal for skull-crushers and squats. Written almost 20 years before its overplayed cousin, Sibelius’s “Finlandia,” “Irlande” is a symphonic poem that both gets you agitated and stirs you to agitate for Irish Home Rule.

Grab a dumbbell and start slowly lifting to the beat of the seductive clarinet opening. Visualize the liberation of the Irish people and the curvature of your future triceps. Next, at a prancing Allegro vivace, get lost in the green pastures of your squat routine. The most common dynamic marking in this section is, obviously, triple forte—as you soon will be. 9/10

Note: This piece was a favorite of Irish revolutionaries Maud Gonne and W.B. Yeats, the latter of whom approached Holmès to compose an opera on his work. She was too busy for him. (Virile.)

2. “Andromède” (1883)

As Lionel Salter wrote in Gramophone in 1994: “There is nothing in the least ‘feminine’ (if one may use that word in these politically correct times) about the challenge flung out by the brass at the start of ‘Andromède.’”

Although for pure size reasons “Andromède” had to come second, this symphonic poem is undeniably virile. What’s that? A monumental brass opening like a shirt being ripped open by the winds of fate? Strings crescendoing into a tornado until they blow their—be warned, there is a grand refractory pause at minute four. Yet, as a truly virile composer, Holmès is soon back in action to paint the hero Perseus flying on his winged horse to free the princess chained naked to a rock (virile). 10/10

1. “L’Ode triomphale” (1889)

Holmès’s “Ode triomphale” is so virile that it has never been recorded. Scored for a 300-piece orchestra and 11 separate choirs, this magnum-sized opus premiered at the Paris World Exposition for the unsheathing of France’s largest phallic symbol, the Eiffel Tower.

We can only begin to imagine how virile it sounded to the 15,000 who went to the Palais de l’Industrie in 1889 to watch a veiled, chained woman appear on a darkened stage, suddenly replaced by fanfares to celebrate La République. Virilely, Holmès had a hand in everything: she rehearsed the choirs, directed the conductor(s), sketched the sets, and insisted that the third night of performance be free for the public. A full 1,200 musicians participated—a size record (Mahler, a fan, was clearly taking notes). After the performance, the public flooded the stage and the London Musical Courier reported that Holmès was carried through the streets in celebration.

Virility score: Mere numbers cannot contain it. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 800 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.