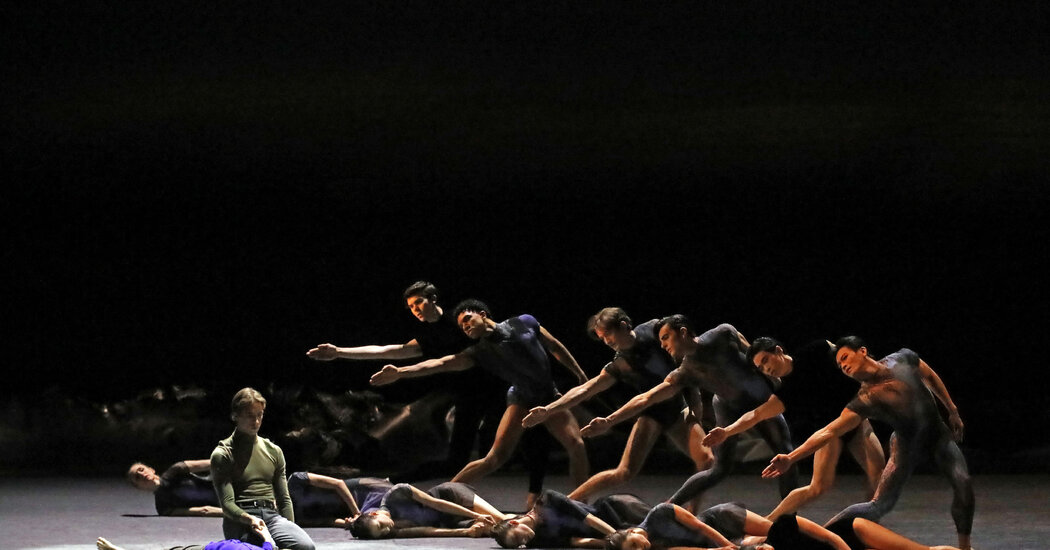

How does a body stand upright when the world is spinning around it? Or, worse, when that world is breaking down with such vehemence that the air seems to grow more toxic by the minute? In Alexei Ratmansky’s new ballet “Solitude,” dancers waver and buckle as inner and outer forces wreak havoc on their bodies. Within this stark, dark universe, set to music by Gustav Mahler, bodies live on the edge, leaning and bending precariously as they fight for equilibrium. They are disjointed, their body parts at odds with one another. Spines twist deeply, as if wringing out the torso could also unleash the rawest pain.

Ratmansky’s latest ballet, his first as artist in residence at New York City Ballet, is about war — the devastating war in Ukraine, the country where Ratmansky grew up and where his parents still live. This month marks two years since the Russian invasion, and there seems to be no end in sight.

Dedicated to “the children of Ukraine, victims of the war,” the ballet, which had its premiere on Thursday at the David H. Koch Theater, was inspired by a photograph of a father kneeling next to the body of his 13-year-old son after he was killed by a Russian airstrike at a bus stop in Kharkiv. The father held the boy’s hand for hours.

That grief — the solitude of “Solitude” — is apparent from the start. The principal dancer Joseph Gordon kneels before the limp body of Theo Rochios, a young student of the company-affiliated School of American Ballet. Rochios, in a bright blue shirt — it lets him nearly glow in the darkness — lies flat on his back while Gordon holds his hand.

The motionless form of Gordon, wearing pants and a tight army-green turtleneck that calls to mind Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, is searing. Couples spring onto the stage from the opposite side, bursting across like fast-moving clouds. Pairs of dancers, each grasping a single hand, pull away until they break apart and then, just as quickly, conjoin with a partner’s back leg bent in an attitude position.

Throughout “Solitude,” limbs are shown at brittle, broken angles or sometimes even like weapons. At one point, the women are carried offstage with a bent knee and a straight leg raised in the air; when their bodies are flipped, they’re like guns aimed into the wing. From time to time, the men pause to stand on one leg while crossing the other in front and holding it by the shin — balancing like amputees. When Ratmansky’s images register through the stage’s darkness, they’re chilling.

While hauntingly somber,” Solitude” has fullness and force. Its score — the third movement funeral march from Symphony No. 1 and the fourth movement Adagietto from Symphony No. 5 — creates a theatrical mood but, more crucially, it works as music for dancing. The funeral march is solemn yet persistent with buoyant klezmer moments, while the shimmering Adagietto, though beautiful, is more distressing. It brings to mind “Kindertotenlieder,” Mahler’s songs on the death of children.

Rochios, moving with the kind of innocence and simplicity that stops time, rises from the floor and is eventually guided along by others, including a serene Sara Mearns, in transparent black, moving with gravity and exquisite tranquillity — a dark angel figure? — and a striking Mira Nadon, her dancing, throughout, dazzlingly robust. As Rochios is lifted into the air, his tiny form is seen being passed in the background: The image, its matter-of-factness, is heartbreaking.

Mark Stanley’s lighting is broodingly dim; with the details of people obscured, you sense shapes and shadows. Dancers seem to guard their eyes from one another as if they know things we don’t. They are nameless bodies lost and forgotten by war.

And then the stage clears, paving the way for the centerpiece of “Solitude,” a solo for Gordon — a lament, as much for his body as his mind. Subtle shifts of weight and lingering tilts dip into the language of modern dance as Gordon’s head drifts to the side and his arms linger and reach. But there is contrast, too, as Ratmansky extracts meaning from movement: Wilting and sagging, Gordon springs into the air for swift jumps that land and morph into tight, anxious spins.

For all his presence and might, Gordon drifts across the stage like a ghost: a hollow hero whose virtuosity is a reflection of a spinning mind. His body is in a continual state of suspension and elasticity. He can’t stand straight no matter how hard he tries.

Costumes and scenery — along the back of the stage appears to be a tangle of rocks and wire, like a military fortification — are by Moritz Junge. When light suddenly breaks through the dusky sky, it seems, at first, like the dawn of a new day. But when Rochios takes his place back on the floor, that flash of light isn’t a burst of hope, it’s a bursting bomb. The ballet ends how it started: a man kneeling next to the body of a boy.

Before becoming City Ballet’s artist in residence, Ratmansky choreographed six ballets for the company — imaginative and vivid, each one building on the next. “Solitude,” a ballet that warrants many repeat visits, has picked up on that momentum. But it wasn’t alone on the program.

“Solitude” was book-ended by “Opus 19/The Dreamer” (1979), by Jerome Robbins, featuring another meaty part for a male lead (originally Mikhail Baryshnikov), interpreted here by Taylor Stanley with a kind of architectural vulnerability and grace; and George Balanchine’s powerful “Symphony in Three Movements.” In “Opus 19,” Unity Phelan blazed with unselfconscious mystery, and “Symphony” featured dynamic debuts by David Gabriel — elegant, expansive and ready, I hope, to rise through the ranks — and a charming, relaxed Isabella LaFreniere, playful up top with legs of steel down below.

Of the two ballets, the more important is “Symphony in Three Movements” (1972) — both overall and in this context: It’s a war ballet, too, though it’s chilly, more austere and bombastic. Set to mainly driving, propulsive music by Stravinsky — who talked to Balanchine about using the score when Balanchine visited him in Hollywood during World War II — the ballet is magnificent, driving along at a thrilling speed. It starts with 16 women, all in uniform white — gorgeous and frightening — poised in a diagonal line as if ready for battle.

In this sharp program, City Ballet presents two ways of looking at war. Balanchine’s is explosive and, at times, victorious; Ratmansky’s is endless and harrowing. But this week in dance was remarkable for something else, too: the male solo. That is, a particular kind of male solo: understated, as airy as it is powerful.

In both Ratmansky’s “Solitude” and in “Brel,” a new work by Twyla Tharp currently at the Joyce Theater, the solos are major, each gleaming in individual ways. What they have in common is their sophistication and depth. They show what can be done with ballet steps while leaving behind any pomposity. These aren’t the kind of dances you interrupt with applause. You let them flow.

New York City Ballet

Though March 3 at the David H. Koch Theater, nycballet.com