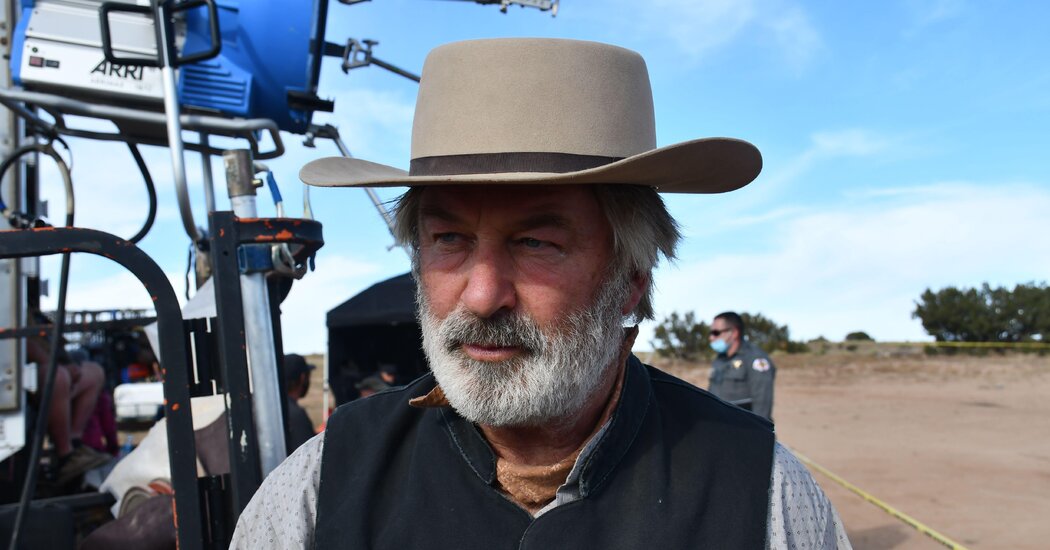

The actor Alec Baldwin is scheduled to go on trial next month for involuntary manslaughter in Santa Fe, N.M.

Baldwin’s long journey to the courtroom started on Oct. 21, 2021, on the set of the western movie “Rust,” when the gun he was holding while blocking out a shot discharged, firing a live round that injured the movie’s director, Joel Souza, and killed its cinematographer, Halyna Hutchins.

It was an almost unimaginable tragedy, but Baldwin soon found himself in legal jeopardy, too. The subsequent saga has amounted to a high-stakes version of a familiar Baldwin ritual: He does or says something controversial; then, in an attempt to be understood, he doubles down on whatever he said or did, inviting further scrutiny; finally, feeling victimized and aggrieved, he vows to stop engaging with the media.

He was in this third stage by the time I started reporting a few months ago. To trace the improbable arc of his prosecution, I interviewed more than 30 people in New York and Santa Fe, reviewed numerous public court filings, police records and videos, and obtained additional documents under New Mexico’s freedom-of-information act.

It’s been a challenge to follow the case through all of its many twists and turns. Here’s what you need to know as the trial approaches.

Troubling details quickly emerged about the film’s set.

The shooting occurred at 1:46 p.m. at the Bonanza Creek Ranch, a family-owned Old West movie set about 20 miles southeast of Santa Fe.

Almost immediately, troubling details began to emerge about the film’s set. There were two accidental firings of blank rounds before the accidental discharge that killed Hutchins, and several members of the camera crew had resigned the night before the incident, citing, among other things, safety concerns. The armorer, who maintains control of all of the film’s firearms — and there were a lot, as this was a western — was just 24 years old and inexperienced.

The local district attorney in Santa Fe, Mary Carmack-Altwies, did not rule out the possibility of criminal prosecutions. “All options are on the table at this point,” she said.

The case against Baldwin was about more than just the shooting.

Baldwin was worried about his criminal exposure from the beginning: Not only was he the actor holding the gun that killed Hutchins, but he was also a producer of “Rust.”

In a series of phone calls and text messages, later released by the Sheriff’s Department, he tried to explain to the detective leading the case that all film productions seek to save money and that it’s not an actor’s responsibility to check his firearm.

Baldwin’s enemies on the political right, meanwhile, pounced. Donald Trump, whom Baldwin impersonated on “Saturday Night Live,” went so far as to suggest that the shooting might not have been accidental.

Baldwin tried to clear his name in an interview on ABC with George Stephanopoulos. But the effort backfired when he said that he only pointed the gun at Hutchins because she had guided it in her direction and when he denied having ever pulled the trigger.

To Carmack-Altwies, he seemed unrepentant. And she didn’t believe his claim about the trigger. “Did he just waltz himself into charges?” she asked her deputy.

The prosecution took place in a tense political context.

District attorneys are elected officials, and charging decisions don’t take place in a vacuum. They are specific to a time and place. And New Mexico is a place with a fraught relationship with outsiders. The state’s official nickname is the Land of Enchantment, but among some Santa Fe locals, it’s known as the Land of Resentment, an allusion to its long history of occupation and exploitation.

New Mexico is also a rural hunting state with a strong gun culture, and it takes gun safety seriously.

As the investigation continued and the possibility of criminal charges loomed, Baldwin was growing resentful himself. “This was something that was to the delight of people who hate my guts politically,” he told Chris Cuomo in an interview during the summer of 2022.

On Jan. 19, 2023, Carmack-Altwies announced her intention to charge Baldwin with involuntary manslaughter, and she followed up the news conference with a slew of national media interviews.

The case unraveled before it got back on track.

Almost as soon as the charges were filed, the case began to unravel, thanks to a series of legal challenges from Baldwin’s lawyers.

Carmack-Altwies stepped down from the case and tapped an Albuquerque lawyer, Kari Morrissey, to lead the prosecution. Weeks after taking over, Morrissey withdrew the charges.

It looked to Baldwin as though he might be in the clear. He thanked his lawyer in an Instagram post and began cooperating with a documentary film about him and “Rust” that he hoped would be sympathetic.

He was not in the clear. Months later, in the fall of 2023, Morrissey told Baldwin’s lawyers that she intended to refile the charges. She offered Baldwin a plea deal but withdrew it after learning that he had been pressuring potential witnesses to sit for interviews for the documentary.

Justice . . . or vengeance?

In many ways, the story of Baldwin’s prosecution has come to resemble a western movie itself, testing the line between justice and vengeance.

Baldwin has been at the center of the media maelstrom surrounding “Rust” for nearly three years now. During that time, his wife, Hilaria, has given birth to their seventh child, even as he has lost work and been party to several potentially costly civil suits.

But Baldwin has rebounded from other controversies in the past, and the half-life of a scandal has maybe never been shorter — even, as may be the case, when it ends in a felony conviction.