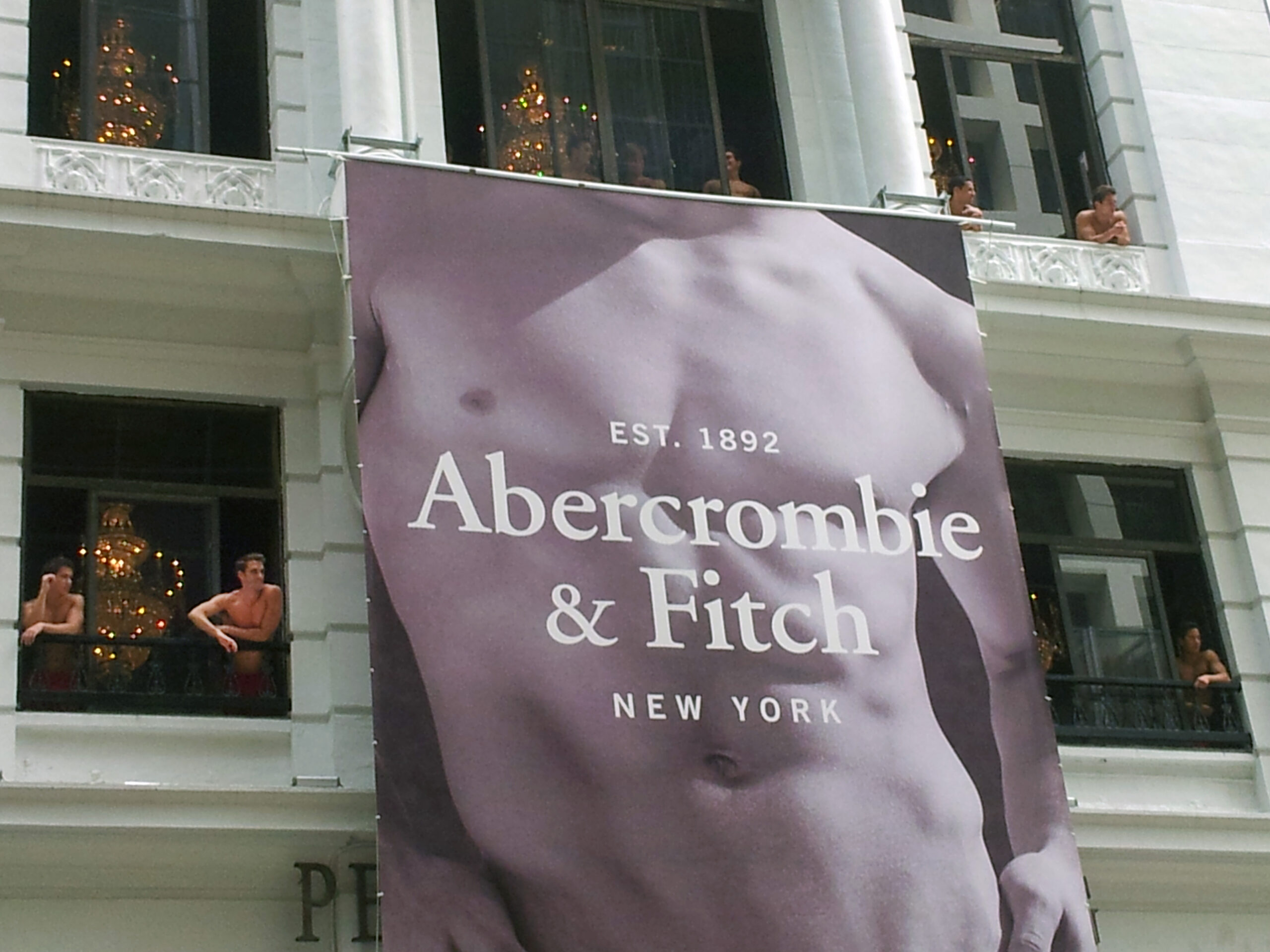

A&F Hong Kong store opening, 2012. 製作, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In May of 2005, discontent with my job as a photo editor at a women’s magazine, I accepted an offer from a friend who did Bruce Weber’s casting to interview for a photo assistant position with him. At the time, Weber was doing the photography for Abercrombie & Fitch, working in tandem with the CEO, Mike Jeffries, to resurrect the brand. The photographs, in tonally rich black-and-white or vivid color, showed cheerful, cartoonishly chiseled, (mostly) white people frolicking, washing dogs, and generally playing grab-ass. They hearkened back to the scrubbed cleanliness of the fifties (with a sprinkle of Leni Riefenstahl); everybody looked like they had gotten a haircut the morning of the shoot. My friend described the photo assistants as a group of young men who traveled the world with Weber, making big money. On breaks, they’d show off for the models by playing shirtless football on the beach or jumping off cliffs into narrow pools of water. This seemed better than sitting at my desk arranging catering or reassuring Missy Elliott’s team that the mansion where we were going to photograph her did in fact have air-conditioning.

The day of my interview, I put on a gray sweater, a striped oxford, and A.P.C. New Standards. I wanted to look tidy, but not too uptight. As requested by the first assistant, I brought a CD of my pictures to demonstrate my photography skills. The office was open plan, with a large round table in the middle and twenty or so people milling about. Weber, a bandanna-ed Santa Claus type, shuffled around chatting with his employees, trailed by a pack of identical golden retrievers. I sat down with Weber’s first assistant, whom I’ll call Sean. Sean told me he had been photographed by Bruce (we kept talking about “Bruce” as if he were imaginary, even though he was standing a few feet away) when he was a NCAA wrestler. He had close-cropped blond hair, and the lingering musculature of a former athlete (I later came across Weber’s pictures of him and his teammates in the locker room, showering cheerfully). The job, as Sean described it, was to hand Weber an unceasing flow of Pentax 6×7 medium-format cameras that had been preloaded with film, focused and set to the proper exposure so he could photograph continuously without technical fuss.

We clicked through the CD of my photographs and he complimented my use of color. While we talked, I looked around the office at the other assistants, a variety pack of hunks. Among them were an Ashton Kutcher type, a Patrick Bateman type, and the all-American boy interviewing me. Wrapping up the interview, he told me that they needed to take a Polaroid because Bruce “needed to be able to put a face to the name.” I stood up and posed for the Polaroid, made with a vintage land camera. I knew this moment was to be my undoing. I am under six feet and, according to my sister’s 23andMe, our family is 99.3 percent Ashkenazi Jew. This type seemed absent from the roster. I suspected I was not there to fill that void. We shook hands, and I got in the elevator and left. After a few calls over the next few weeks, things tapered off and I never heard from them again. Sometimes I wonder if they saved those Polaroids, and if it would be possible for me to get mine back.

Shortly after my interview, an Abercrombie flagship store opened on Fifth Avenue and Fifty-Sixth Street. Aside from the overpowering stench of their cologne Fierce (an “irresistible blend of marine breeze, sandalwood, musk and wood notes”) and the moody lighting, both A&F retail signatures, the Fifth Avenue store was notable for its centerpiece, a mural called The Locker Room. This was painted by the artist Mark Beard, under one of his many aliases, Bruce Sargeant. (The name Bruce is inexplicably historically associated with being gay; for example, when the Incredible Hulk comics were adapted for television, Bruce Banner’s name was considered too fey, and changed to David.) The mural depicts an early-twentieth-century gym class in a style that evokes Thomas Eakins: young men in baggy loincloths or singlets, doing calisthenics and climbing ropes. Like Weber’s flawless crew of assistants, the romantically rendered athletes were perfect manifestations of the hairless-and-wholesome masculinity defined by his work for A&F. Homoerotic, suggestive, but never explicit. You could be spotting your pal as he climbed a rope or playfully pulling your buddy’s underwear down all in good fun! The photos from the store’s opening show the live version: groups of unnamed shirtless guys carrying around the (blond, rosy-cheeked) model Heather Lang, chastely kissing her on the cheek.

These festive days are now over. In July of 2023, Abercrombie closed its Fifth Avenue flagship and converted the Hollister (a sister brand) down the block to replace it. The CEO, Fran Horowitz, said of the consolidation: “It’s 180 degrees from the cavernous, dark club feeling of the past … This is the antithesis of that.” In the decades between my ill-fated interview and the store’s closing, Abercrombie saw a slew of sexual abuse scandals involving Weber and Jeffries. Weber was accused of molesting male models while photographing them (sticking his fingers in their mouths, et cetera) and settled their lawsuits for a undisclosed amounts. The allegations against Jeffries (and his romantic partner) involve a middleman named James Jacobson, recognizable by the snakeskin patch he wears over his nose, possibly due to a botched plastic surgery. Jacobson was said to have recruited hundreds of young men for Jeffries and coerced them into sexual favors by tantalizing them with the possibility of modeling careers. Very Epstein-like indeed, and coincidentally (or not?) Epstein was the money manager for Les Wexner, the man who not only brought Jeffries on to A&F but once owned Victoria’s Secret as well. Wexner (along with Dov Charney) was the architect of the New American Horniness that sprung up in the aughts and supposedly died with #MeToo, Hikikomori Zoomers, and the pandemic.

On a recent trip to Midtown with some time to kill, I found myself looking for the A&F store to revisit Sargeant’s mural. This was when I realized the store had moved, and that the mural had been uninstalled in 2018. (It was reconstructed in Beard’s studio, before being cut up into smaller paintings and shown at the Carrie Haddad Gallery.) The new A&F store has an open plan, ficuses, and bright overhead lights. The only art is bland travel photography. I wandered around, taking inventory of a tepid mix of preppy basics, Nirvana kids’ T-shirts for the children of Gen Xers, and a conspicuous lack of A&F logos. The strategy is working: the company’s stock went up 300 percent in 2023, their scandalous past is long gone. And Bruce? He seems to be doing fine. In a recent Instagram post, he shared a photograph of seven golden retrievers, including a new puppy, who, after much debate, was christened Spirit Bear.

A&F Hong Kong store opening, 2012. 製作, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Asha Schechter is an artist and writer living in New York City.