The best documentary award became part of the Oscars in 1942, and the list of winners is genuinely fascinating. In the category’s early years, the State Department and various branches of the U.S. military were routinely nominated, and even won. As time wore on, films critical of the government and its policies — whether the focus was labor, nuclear war or the surveillance state — were more likely to take home the prize. At the Oscars, the documentary category might tell us more about America than any other.

One of my favorite winners is from 1970: Michael Wadleigh’s “Woodstock” (for rent on major platforms). It ran more than three hours when it was first shown; a 1994 director’s cut stretched to nearly four. The film is a document of the seminal 1969 music festival near Woodstock, N.Y., which has in the decades since taken on almost mythic proportions in American culture, a touchstone for boomers and everyone after.

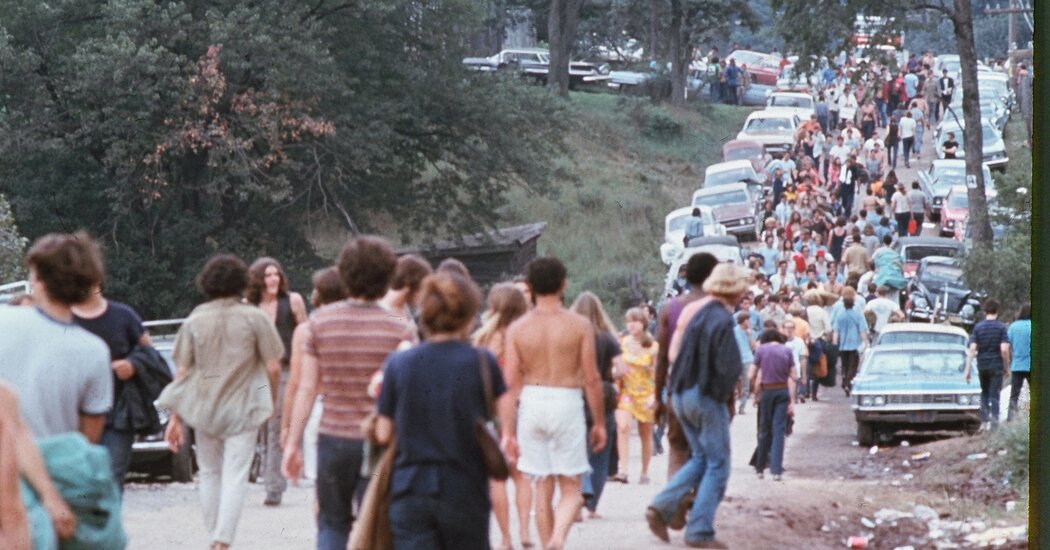

What’s clear from the movie is how Woodstock was very nearly a catastrophe, logistically speaking. Far more people showed up for the three-day festival than anyone had expected. There wasn’t enough food to go around, and the whole unsheltered crowd nearly fried in an electrical storm. It’s easy to imagine violence breaking out, or some other terrible event that would consume cultural memory. In fact, that did happen a few months later, when a teenage Rolling Stones fan was stabbed and beaten to death at the Altamont Speedway, an event captured by Albert and David Maysles in their 1970 film “Gimme Shelter.” (“Everything that people feared would happen (but didn’t) at Woodstock happened at Altamont,” the New York Times critic Vincent Canby wrote of that film.)

“Woodstock” is a mesmerizing watch, as the cameras roam from the stage to the organizers’ chaotic approach to managing the crowd to the many ways that attendees figured out how to take care of one another. (And there is, of course, the music.) Just as the festival threatened to veer out of control at any moment, the filming was a skin-of-the-teeth operation, with a team populated by many young and relatively inexperienced filmmakers. Perhaps that’s why it ended up working.

In fact, that’s why I’ve been thinking about it: out there in the mud holding a camera was a very young Martin Scorsese, fresh out of film school. According to cameraman Hart Perry in a Rolling Stone article about “Woodstock,” Scorsese tried to nap under the stage in a pup tent, knocked over the pole and got stuck in the tent. “He had claustrophobia and was screaming for somebody to help him,” Chew said. “But he wasn’t Martin Scorsese yet, he was just some schmuck from Little Italy.”

Scorsese, of course, went on to become someone. This year his drama “Killers of the Flower Moon” is nominated for 10 awards at the Oscars — and one of those is for Thelma Schoonmaker, his longtime editor. She and Scorsese began their work together in 1967, with their first feature, “Who’s That Knocking at My Door.” Soon after, she worked as an editor on, you guessed it, “Woodstock.” For moviegoers, the documentary’s legacy stretches far beyond its subject.