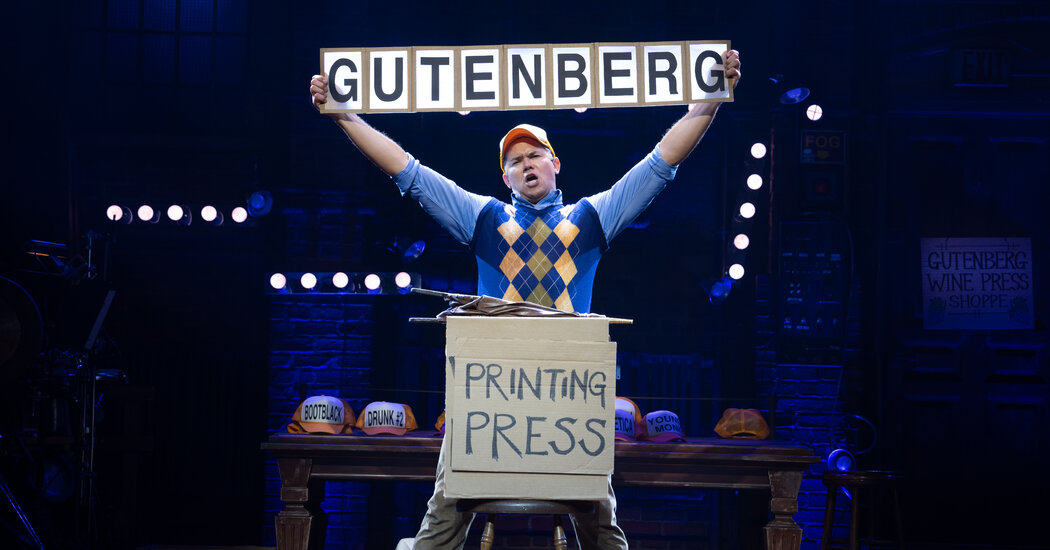

“Gutenberg! The Musical!,” a comic meta-musical about two talentless dolts pitching a show about the father of the printing press, wraps up its limited Broadway run on Jan. 28.

Written by Scott Brown and Anthony King and starring Josh Gad and Andrew Rannells (reprising their “Book of Mormon” buddy act), the show has drawn mixed reviews and strong box-office returns. But even before it opened, its mere existence on Broadway sent book and library nerds vibrating with anticipation and a bit of disbelief.

There have also been grumblings from some traditionalists (of the rare book, not the Rodgers and Hammerstein, variety), along with some resignation. Well, why not a musical about Johannes Gutenberg? If Broadway can turn a semi-overlooked founding father like Alexander Hamilton into a household name and cultural hero, why should the guy whose invention helped jump-start mass literacy throw away his shot?

Hamilton had some big fat biographies on his side. But as Gad’s character in the show notes, Wikipedia (correctly) declares records of Gutenberg’s life “scant.”

Here is a primer for those who, even after seeing the show, might be left wondering: “Guten-Who?”

What do we actually know about Johannes Gutenberg?

Born the son of a patrician in the early 15th century, in Mainz, Germany, Gutenberg was originally trained as a goldsmith and metallurgist. A few surviving documents suggest that in the 1430s he began secretly developing what would become his famous printing press. His early efforts included some papal indulgences and a grammar book. Then, in late 1454 or early 1455, seemingly out of nowhere, came his monumental two-volume, nearly 1,300-page Bible, with its two columns of 42 lines per page.

Today, specialists describe Gutenberg’s accomplishment precisely. His Bible “was the first substantial book printed in the West from movable type,” George Fletcher, the author of “Gutenberg and the Genesis of Printing,” said during a recent interview at the Grolier Club in Manhattan, where I visited recently for an up-close look at some of Gutenberg’s printing, including loose leaves from his Bible.

So did Gutenberg really “invent” the printing press?

Not exactly — though bringing this up over a pint of mead at the Rusty German, the seedy tavern in the show, might get you in trouble. As far back as the late eighth century, Japanese artisans were mass-printing Buddhist sutras using carved woodblocks. And a form of movable type appeared in China as early as the 11th century, though it’s unclear whether Gutenberg would have known of it, Fletcher said.

Yet the world-altering nature of Gutenberg’s invention lay not in the press, Fletcher said, but in his whole system, starting with the type sorts (as specialists call the individual characters). “What is important is this ability to reuse and reuse and reuse the type sorts, in any combination conceivable,” he said. “You have 26 letters, but you can get millions of combinations out of them. And he figured out how you could do this.”

Did the Gutenberg Bible really help teach Europe’s illiterate masses to read, as the show’s character’s claim?

“There’s a great deal to that,” said Fletcher, a former curator at the New York Public Library (which owns one Gutenberg Bible) and the Morgan Library & Museum in Manhattan (which has three). Between about 1455 and the end of 1500, roughly 30,000 different editions of printed books appeared, amounting to millions of copies, all over western Europe, and as far as Constantinople. “And by the 1490s, there was all sorts of stuff being cranked out,” he said. “So there was much more material for people who could read or could learn to read and better themselves.”

Did Gutenberg battle the religious authorities?

The musical depicts Gutenberg as locked in a battle with an evil monk, who fears the printing press will loosen the church’s power over the masses.

In reality, some religious readers were highly impressed with Gutenberg’s wares, including the future Pope Pius II, who saw a sample at the Frankfurt Book Fair in early 1455. He wrote excitedly to a cardinal in Rome, praising Gutenberg and his pages, which he declared “exceedingly clean and correct in their script, and without error, such as Your Excellency could read effortlessly without glasses.”

Unfortunately, the future pope noted, the run of roughly 180 copies had already sold out.

Was Gutenberg really in love with a wench named Helvetica, like in the show?

Unlikely. Helvetica is the name of a now-ubiquitous clean-lined typeface created in 1957, which shot to world domination after being selected as a core font in the earliest Macintosh computers. The typeface Gutenberg used, which mimicked the look of calligraphic handwriting, is known as blackletter.

What happened to Gutenberg after his Bible?

Shortly after the book was announced for sale, he had a dispute with one of his funders and lost his press. “He got thrown out of the business, just at the point of success,” Fletcher said. Gutenberg died in 1468, at around the age of 70. His gravesite is unknown. A history of the world published in 1482 by William Caxton, the first printer in Britain, omitted his name but noted the revolutionary technology born in Mainz, saying, “the craft is multiplied throughout the world, and books be had cheap, and in great number.”

Where can I buy a Gutenberg Bible?

Sorry, you’re out of luck! The last one to come up for auction, in 1978, fetched $2.2 million, roughly $10 million in today’s dollars. Today, all 49 of the substantially complete Gutenberg Bibles known to survive are in institutional collections.

Single leaves, known in the trade as Noble Fragments, do come up for sale and cost roughly $70,000 to $100,000, a bit higher if on vellum rather than paper, said Selby Kiffer, a senior vice president at Sotheby’s. (The Grolier owns several Gutenberg leaves and other fragments.) If a whole Bible should come to market, Kiffer estimated, the price would be a record-obliterating $60 million to $80 million.

Yet the remarkable thing about Gutenberg’s work may not be its rarity, but its enduring familiarity. “We may be in a digital world now, but from 1455 to today, the book as a technology hasn’t changed that much,” he said. “And certainly, the craftsmanship hasn’t improved since Gutenberg.”

Are there any other early printers ripe for a Broadway close-up?

The best bet is probably Aldus Manutius, a leading printer in late-15th-century Venice, where the center of printing innovation moved a decade after Gutenberg. Aldus pioneered the printing of portable, relatively affordable editions of classics, which transformed personal reading. He was the first to print editions of Aristotle, Thucydides, Herodotus and Sophocles; the first to use italic type; and the first to use the semicolon in its modern sense.

Aldus was a famously irascible character. And if you believe Robin Sloan’s 2012 novel, “Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookshop,” he was also the founder of the Unbroken Spine, a secret society of bibliophiles locked in a 21st-century existential showdown with Google over the soul of humanity.

But then, why not believe it? As Gad’s character puts it in the show, historical fiction is “fiction that’s true.”