Dragnet Girl (1933).

Kristin here –

Due to health problems, we have been reposting older entries lately and will continue to do so. Still, I could not skip this year’s contribution to the inexplicably popular series of ten-best lists for ninety years ago. Previous lists can be found here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930, 1931,and 1932.

Last year’s list was easy to fill with marvelous films. Surprisingly, 1933 proved to be a thin year for masterpieces. The major auteurs of Hollywood and France created relatively minor films and German filmmakers were busy finding safe places to live and work. In short, there were some obvious films to head the list, but there are some titles here that I would include in a stronger year.

Fortunately one of the greatest filmmakers hit his stride in 1933. Yasujiro Ozu made three films that could be among the top ten. I usually don’t put two films by the same director on these lists, but I’m including two of his (sorry, Woman of Tokyo). Earlier Ozu films that featured on these lists can be found in the 1930, 1931, and 1932.

Dragnet Girl

2023 has been the 120th anniversary of Ozu’s birth and the 60th anniversary of his death. Retrospectives and exhibitions internationally have no doubt widened fans’ awareness of his earlier films. For decades almost none of his films made before Late Spring (1949) were much known outside Japan. Ozu’s gentle family dramas were so familiar that few would have believed that he began with genre films: student comedies, family comedies, salaryman comedies, and even gangster films. Now, fortunately, his entire surviving output is available on DVDs and Blu-rays, though sometimes not in versions with English subtitles.

The Criterion Collection’s Eclipse series brought the best of the very early films to DVD, including the two Ozu films on this list.

Film buffs familiar only with Ozu’s late films might well ask, could Ozu make a good gangster film? Actually, he could make a great one. Dragnet Girl is one of his early masterpieces.

Ex-boxer Joji is a small-time thug, living of his mistress, Tokiko. An aspiring young boxer and wannabe gangster, Hiroshi, idolizes Joji and spurns his sister Kazuko’s pleas to stay in school. Joji falls for Kazuko, and Tokiko finds that she likes the girl and wants to emulate her by persuading Joji that they should leave their lives of crime. But there’s one last job …

The style is quite noir, and Ozu has fun playing with the various Nipper figures and decals in the music shop where Kazuko works (see top). And Kinuyo Tanaka, best known in the West for tragic roles in Mizoguchi films, does quite well as a gangster’s moll (above).

Dragnet Girl is available on DVD in the Criterion Collection’s “Silent Ozu–Three Crime Dramas” and streams on The Criterion Channel.

Passing Fancy

As part of the slow discovery of Ozu’s work outside Japan, Western audiences finally got a glimpse of his early work when I Was Born, But … became available. As wrote last year, it “may be the one where he achieved the perfect balance of humor and poignancy that characterizes so many of his best films.” Or maybe it was Passing Fancy that struck that balance perfectly.

In a way, Passing Fancy reverses the premise of I Was Born, But …. In the earlier film, two boys become petulant and rebellious when they realize that their respected father is a mediocre salaryman taking orders from a wealthy boss and even playing the clown to entertain party guests for the boss. The parents realize the sadness of their situation but manage to handle the boys with understanding.

In Passing Fancy, the father, Kihachi, is an illiterature, carefree worker who approaches his duties as a single father to his bright son Tomio. Tomio acts as the parent, dragging his father out of bed, dressing him, and seeing him off to work. Tomio strives for an education, insisting on doing his homework when Kihachi tells him to go out and play. The two get into a serious argument, and their reconciliation (above) is one of Ozu’s most poignant of many poignant scenes.

As David says in his book on Ozu, Passing Fancy is more focused around complex characterization than his other early films. The secondary characters include Harue, an unemployed young woman, whom Kihachi briefly believes he can woo despite being considerably older (the “passing fancy” of the title). There is Kihachi’s cynical friend Jiro, who accuses Harue of being a gold-digger and rejects her growing love for him. The plot focuses on the characters and their changing attitudes, especially Kihachi’s alternation between fits of fatherly responsibility and selfishly neglectful behavior.

Passing Fancy is available on DVD in the Criterion Collection’s “Silent Ozu-Three Family Comedies” and streams on The Criterion Channel. The same link leads to David’s discussion on editing in Passing Fancy in our “Observations on Film Art” series. A PDF of his book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, is available for free here.

Design for Living

Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise (1932) is generally considered one of his very best films. It tends to put Design for Living in its shadow. Still, this Ben Hecht adaptation of a Noel Coward romantic comedy is nearly as good, with three marvelous stars–Gary Cooper, Frederic March, and Miriam Hopkins–and enough witty dialogue for three features.

It’s also as risqué as anything Lubitsch did, narrowly missing the introduction of the Code in 1934. The three leads, Tom Chambers, a painter (Cooper), George Curtis, a playwright (March), and Gilda Farrell, a commercial artist (Hopkins) meet on a train in France and soon move in together. They swear a gentlemen’s agreement that there will be, as Gilda forthrightly says, “No sex.” This doesn’t work out, as Gilda has affairs with both, one after the other. Eventually they reunite and swear another gentlemen’s agreement–which clearly is leading to a menage à trois.

Design for Living is interesting to contemplate in relation to the Code’s dictates that characters who transgress moral or legal strictures must be punished by the film’s end. Most obviously here the three characters end up settling into a comfy romantic trio. Beyond that, though, Gilda’s desire to become a mother of the arts by guiding the pair’s unsuccessful careers has paid off spectacularly by the end. Her pitiless criticisms of their work (“Rotten!”) goad both of them to fame and fortune. The only one punished by the end is the wealthy advertising executive Max Plunkett (Edward Everett Horton), whose brief, straitlaced marriage to Gilda ends disastrously. The Lubitsch Touch indeed.

Design for Living is available on DVD or Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection and streams on the Channel.

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse

As is well known, Fritz Lang, despite not being Jewish, left Germany for France and ultimately Hollywood in 1933 when Hitler came to power. His last German film until he returned in the late 1950s was The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. The film was banned immediately, with the German version having its premiere in Budapest. A French version, also directed by Lang but with different actors, circulated in Europe and the US, and various recut versions were circulated thereafter.

A sequel to the two-part serial Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (which was on my top-ten list for 1922), Testament took a very different approach to its titular villain. Now Mabuse has become insane and is incarcerated in a mental institution. There he obsessively scribbles down plans for a universal reign of crime. To escape the institution, his spirit enters the body of Dr. Baum, his psychiatrist (above), who becomes his surrogate in leading the gangsters who carry out Mabuse’s plans.

The sequel is not quite up to the original, in large part because the menacing Rudolph Klein-Rogge, who played Mabuse in that film, is barely present here. We see him briefly in his cell and occasional in some sort of spirit form, but Dr. Baum is not nearly as fascinating as a surrogate Mabuse.

Stylistically, however, Testament is pure Lang, with high long shots along dark, deserted streets, art-deco interiors, and a spectacular fire at a gas factory. There’s also a justly famous scene of an assassination from one car to another on a crowded street. Lang also seems to bid good-bye to Expressionism, with a subjective shot from the point of view of an asylum patient (see bottom).

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse is available on DVD from The Criterion Collection and streams on the Channel. The DVD set includes the French version and a restoration of the German version missing three minutes of the original running time.

Zero for Conduct

Zero for Conduct has been another victim of censorship. Jean Vigo’s depiction of the miseries in a school for mainly working-class boys and especially the rebellion that some of the foment was too much for the authorities. It was only discovered after World War II, being released in the USA in 1947 and being taken up by cinephiles and the New Wave filmmakers in France.

I first saw the film as a graduate student. It was a muddy, gray print that did not reveal to me what all the fuss was about. Modern restoration has revealed the details and the luminosity of the cinematography by Boris Kaufman, as in the nighttime dormitory rebellion (above).

Vigo is sometimes referred to as a surrealist director. There are moments in Zero for Conduct that could be described as surrealist, as when the one kind teacher Huguet, draws a carticature while doing a hand-stand or the life-sized dummies that represent the attendees at the school fête where the rebellion breaks out. On the whole, however, the odd touches seem more to represent the way the children see the world, for the film is told largely from their vantage points.

Zero for Conduct is available in its restored version on DVD or Blu-ray in the set “The Complete Jean Vigo” from The Criterion Collection and streams on the Criterion Channel.

A Night on Bald Mountain

It’s not often that a completely new animation technique is introduced, but it happened in 1933. Claire Parker and Alexander Alexeieff had invented the pin board or pin screen method. It involved a perforated board three by four feet, with hundreds of thousands of headless pins stuck through it. By pushing pins forward selectively and casting a raking light across the board, they could create images that resemble moving engravings.

A Night on Bald Mountain is set to Mussorgsky’s tone poem. There is no narrative, only a series of unconnected, disturbing images pass quickly across the screen, often morphing from one shape to the next. The result, as the above images suggests, is eerie indeed.

Given the labor-intensive work required on each film, the pair produced a small number of animated shorts across decades, supporting themselves by making many advertising shorts. The Wikipedia entry on Alexeieff has an excellent summary of the couple’s career and an extensive filmography.

Most prints of A Night on Bald Mountain are too dark. A restored version is included in Flicker Alley’s essential DVD/Blu-ray collection, “Early Women Filmmakers: An International Anthology.” It streams on The Criterion Channel.

Footlight Parade

1933 was a remarkable year for the series of Warner Bros. musicals famous for their numbers staged and choreographed by Busby Berkeley. No fewer than three major titles were released that year: 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933, and Footlight Parade. I can’t put all three on the list, and I suspect the general opinion is that Footlight Parade is the best of the entire series.

It’s far livelier than the others, with the crazy premise that a company forms a service delivering live stage prologues to movie theaters. The result is a frantic race to get from one theater to the next. It has James Cagney, whose fast patter and unique, jittery dancing style injects an energy that offsets the bland Dick Powell. It has a string of big numbers, from “Honeymoon Hotel” to “By a Waterfall” to “Shanghai Lil,” all showing Berkeley at his flamboyant best.

Footlight Parade is available in Blu-ray and other formats from Warner Bros. The image above was taken from a DVD in “The Busby Berkeley Collection,” a bargain boxed setwith five films and a documentary.

Duck Soup

Speaking of surrealism, the Marx Brothers ended their five-film contract at Paramount with what is widely considered their best film, Duck Soup, directed by Leo McCarey.

At Paramount, the brothers were allowed to create messy scenarios without the logic and unity dictated for most Hollywood films–including those made at MGM under the dictates of Irving Thalberg. The result is a series of comic set pieces loosely held together by a plot involving the tensions between two Ruritanian countiries, Fredonia and Sylvania.

The most famous of these set pieces is the mirror scene, where Pinky (Harpo), dressed as Firefly (Groucho), struggles to hide the absence of a broken mirror by mimicking his actions perfectly. Rather than confronting Pinky, Firefly devises ever more elaborate movements to reveal the ruse, inevitably copied flawlessly by Pinky (above). Other comic highlights that have nothing to do with the plot involve Pinky and Chicolini (Chico) running a peanut stand and carrying on a feud with the neighboring lemonade stand run by the master of the slow-burn, Edgar Kennedy.

This feud foreshadows the battle scene at the climax of the film. Staged entirely in the Fredonia headquarters, the action becomes increasingly nonsensical, with Firefly’s military outfits changing at frequent intervals and madcap dispatches coming in from the front.

Duck Soup also has the advantage of not including either of the hitherto obligatory harp and piano solos by Harpo and Chico. There are no such “serious” interludes or subplots involving young lovers, as there would be in A Night at the Opera and other later films. It’s the Marxes’ only film with unadulterated crazy humor throughout.

Duck Soup is available on Blu-ray and other formats here. The same range of formats are available for “The Marx Brothers Silver Screen Collection,” which contains their five Paramount films.

King Kong

King Kong was released only a few years after Universal had seemingly identified ed the horror genre with vampires, sub-human monsters, and old dark haunted houses. Kong was different, a monster that could be sympathized with. Viewers could attribute human feelings to Kong as he saves Ann Darrow from a tyrannosaurus (above). As documentary filmmaker Carl Denham remarks, the giant gorilla’s affection for Ann turns the plot into a beauty-and-the-beast tale.

The film also added a touch of novelty by having Kong climb the Empire State Building, which had been opened to the public only two years earlier.

The impact of the film was no doubt enhanced by Max Steiner’s revolutionary musical track. It used leit motifs and a large orchestra, and the music played for a larger portion of the film than was usual in early sound films.

King Kong also expanded the methods of special effects available to filmmakers with its extensive use of Willis H. O’Brien’s puppet animation for Kong and the dinosaurs of Scull Island. (As I discussed in a previous post, O’Brien’s puppet animation was used extensively eight years earlier in the 1925 version of The Lost World.)

King Kong is available on Blu-ray from Warners. My image is from the out-of-print “Two-disc Special Edition” on DVD.

The Three Little Pigs

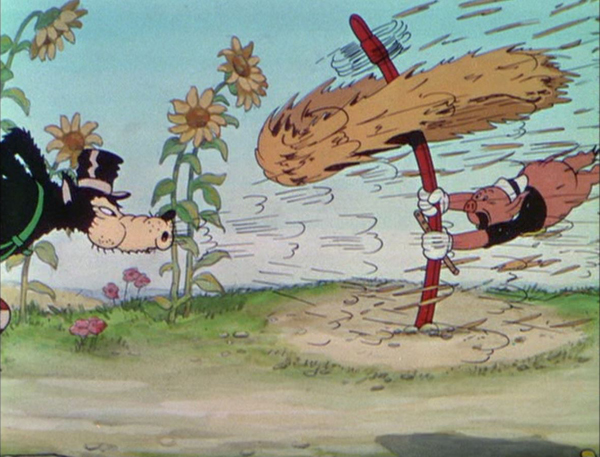

Despite being a major force in the American film industry by this point, Walt Disney has been little-represented in my lists. So far only The Skeleton Dance (1929), the first of the Silly Symphonies, has represented his output. The Three Little Pigs wasn’t a technical milestone in Hollywood animation. The first three-strip Technicolor short was Disney’s bland Flowers and Trees, which won the 1932 Oscar for an animated film (the first years this category was included). The Three Little Pigs won for 1933. In 1994 a large group of professional animators voted it number eleven on a list of the fifty greatest animated shorts. (An interesting list available here.)

Obviously people like the film a lot. It grossed ten times its production cost. It’s considered a classic. It has all the advantages of the best Disney shorts–beautiful color, fast action, and a catchy song, “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” It’s also quite funny. The framed pictures on the walls of the three pigs’ houses are easy to miss, but they characterize each pig cleverly.

The Three Little Pigs is available from multiple sources. My frame was taken from the “Walt Disney Treasures: Silly Symphonies” DVD set. The “Treasures” series, recognizable by its aluminum cases, is out of print and hard to find, though there are a few copies available on eBay. (The same version has been posted on YouTube, but beware, it is distinctly out of focus.)

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933).

This entry was posted

on Sunday | December 31, 2023 at 4:42 pm and is filed under Film comments.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.