The two defining currents of Tamil cinema of the past decade — the engaged, politically aware films of the Pa. Ranjith school and the playful, movie-aware work of the Naalaya Iyakkunar gang — collide head on in Karthik Subbaraj’s Jigarthanda DoubleX (2023), a spiritual sequel to the director’s second feature Jigarthanda (2014). Where the earlier film, arguably its maker’s finest, was a heady celebration of the supremacy of cinematic mythmaking over that of the gun barrel, DoubleX is a much more solemn, spiritually tortured assertion of the importance of cinematic demystification.

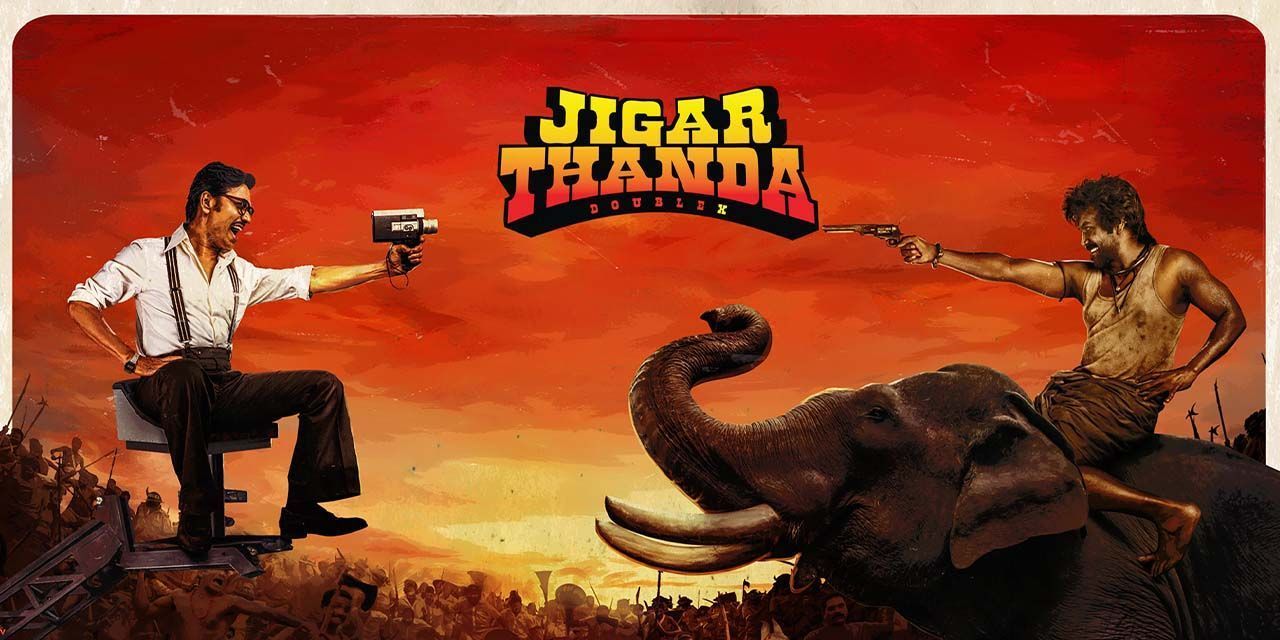

As a filmmaker, Karthik Subbaraj calls to mind those expert craftsmen who keep snipping away at a chunk of folded paper without giving us an idea of where they are going with it, only to unfold it at the end and have us marvel the intricacy of the design and the necessity of every redundant seeming gesture. He begins with pet ideas and images — in this case, again, the primacy of the camera over the gun — and then weaves a convoluted plot over them outwards, allowing the audience to arrive at their beating heart in the middle of a film. Showy? Absolutely. And DoubleX doubles down on the showiness. Every shot is an event – sometimes tiringly so, as in the many ritual shootouts organized in a movie theatre — and dramatic logic makes way for a logic of the spectacle.

Coerced by a cop to kill a ruthless, Clint Eastwood-loving henchman named Caesar (Raghava Lawrence, spitting image of a young Rajinikanth), prisoner Raydas (SJ Suryah) masquerades as a filmmaker to woo his vain target into a celluloid dream and slay him. Raydas and Caesar embark on a movie project together, but they soon find their fiction overwhelmed by reality. Faced with the genocide of a mountainous tribe by those in power, both filmmaker and subject must choose to leave fiction for reality. Rather, transform their fiction into reality.

As the synopsis suggests, the film goes all over the place, and then some, and part of the fun and the frustration is in observing Karthik Subbaraj make straight-faced connections between elements that have no right to be together. His previous film Mahaan (2022) — built around the idea of real-life father and son playing a slippery morality game on screen — was in comparison a lean operation, balancing its two central elements with relative ease. DoubleX, in contrast, is unwieldy — weighed down by seriousness where Jigarthanda was shrewdly unserious and light-footed — overstuffed with dramatic developments, all of which, to be sure, is fleshed out with the director’s characteristic taste for symmetries, repetitions and reversals. A wannabe cop, Raydas ends up as a criminal, pretends to be a filmmaker, only to become a real filmmaker exposing the cops; a petty criminal, Caesar aspires to be a movie star, only to turn into a real hero, who becomes a screen legend. And so on.

After Mahaan, Karthik Subbaraj seems to have grown more comfortable propelling his narrative through characters that aren’t conventionally likeable. For a good while, DoubleX is a veritable parade of inglorious bastards, our identification never resting securely with any of them. But despite Karthik Subbaraj’s self-absorbed cinephilia, there’s a naïve idealism at the heart of his films that keeps them from hip cynicism. Part of the idealism comes from the subaltern political assertion, now domesticated thanks to the work of Ranjith and Mari Selvaraj, that DoubleX borrows and gives a unique spin to: cinema cannot defeat oppression, but it can stand witness to it; art cannot fight malevolent power, but it can influence individuals to change the nature of that power.

DoubleX is Karthik Subbaraj’s first film to release in theatres in many years (Mahaan went straight to streaming), so it is perhaps understandable that he turns it into a sentimental ode to the collective movie experience. The notion that a theatre audience can be outraged by images of oppression and moved to action (a lasting legacy of Shankar’s cinema, where cable news and social media become the keepers of public conscience) is so corny and old-fashioned that it is thoroughly impressive in its sincerity. DoubleX presents it almost as a necessary myth for truth to flourish.

It is curious that we get Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon (2023) and DoubleX within the span of a month. Very different pictures, but both tackle fraught political subjects with an often stifling piety (although Karthik Subbaraj is capable of inserting an absolutely juvenile punchline in a cop’s mouth in the film’s most harrowing scene), expose cinema’s tendency to “print the legend,” yet refuse to stop at this demystification in order to lay the foundations for truth. The worst rogues in DoubleX use cinema as a medium for political propaganda, but it is also put at the service of justice. The camera is neutral, it is those who wield it that make it good or evil. That, perhaps, is the ultimate myth.