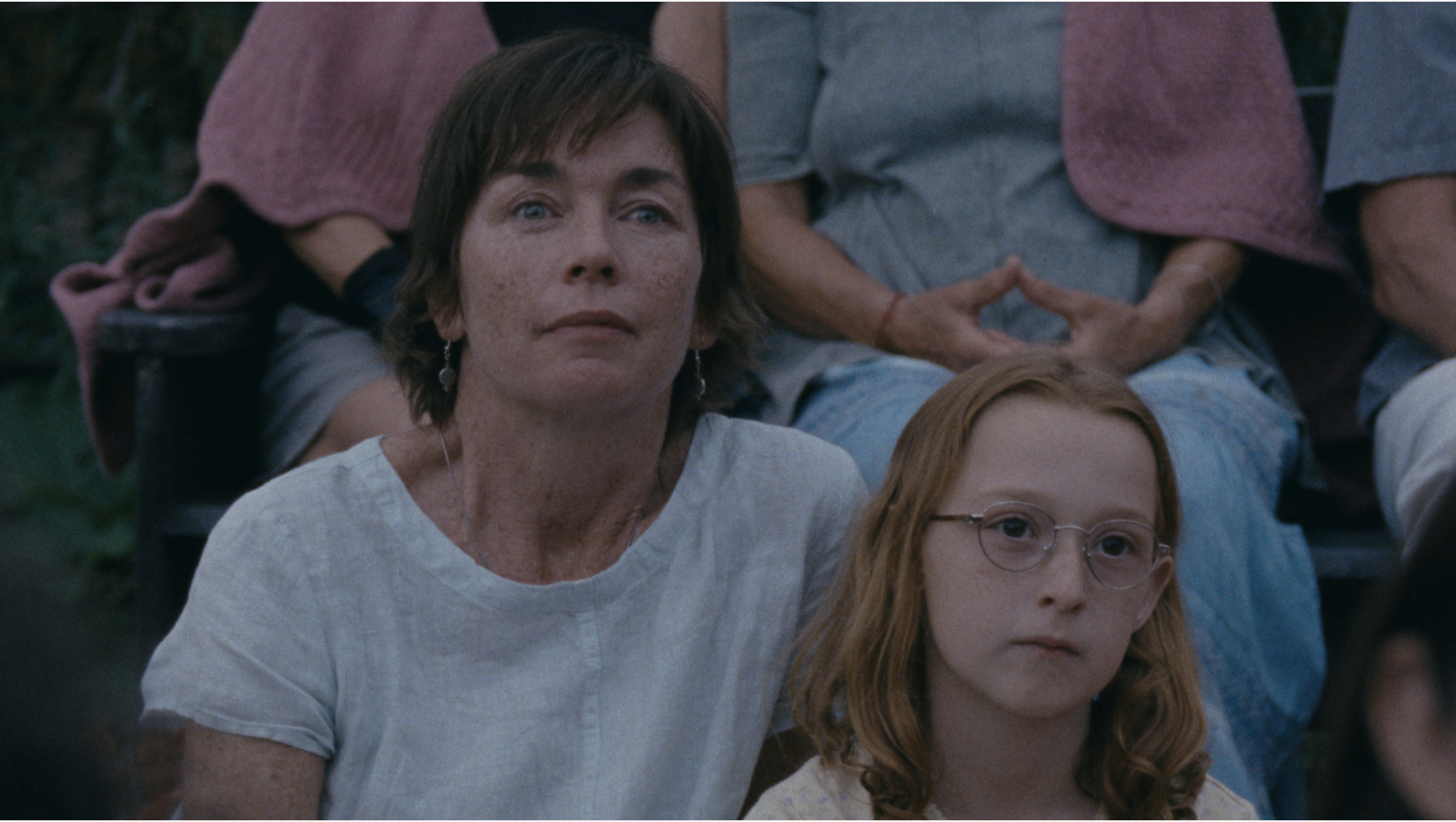

Janet Planet (2023). All photos courtesy of New York Film Festival.

Annie Baker’s Janet Planet is a film that reminded me of what it is actually like to be a child: the boredom and fascination of learning to play a tiny electronic keyboard; the experience of faking illness so diligently that you kid yourself; those self-invented witchy rituals that offer the promise of control. Set in a crunchy Western Massachusetts town and mysteriously infused with the grain of an eighties family photo, it follows Lacy (Zoe Ziegler), an eleven-year-old with a wise, anxious face and a T-shirt down to her knees, and her single mother, Janet (Julianne Nicholson), as their household is disrupted by three visitors. Like Fanny and Alexander, one of Baker’s favorites, it’s a film framed by theater—there’s a culty open-air production with puppets and masks, a dollhouse with mismatched inhabitants. It also contains a scene with some of the best dialogue I’ve heard outside an Annie Baker play (while you’re here: you must read our excerpt of Infinite Life in issue no. 238!), in which two female characters have the kind of argument that only the closest friends can have, while tripping on MDMA.

—Emily Stokes, editor

The Curse (2023).

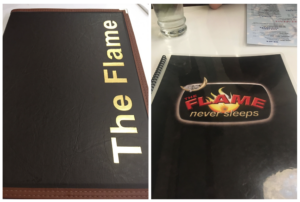

By 8:27 P.M. on Thursday, October 12, the night of the New York Film Festival’s 8:30 P.M. premiere screening of the first three episodes of Nathan Fielder and Benny Safdie’s new gentrification/reality-TV satire, The Curse, we were still standing outside Alice Tully Hall, at the front of a barricaded queue. To our right was a man in all black and Bluetooth headset, whom one of us assumed was famous and the other mistook for a security guard until he asked, somewhat conspiratorially, “Orchestra left or orchestra right?” We told him we hadn’t picked up our tickets yet. Past the security line, our companion disappeared into the crowd; we noticed that someone else’s companion, standing in line for the bathroom, was Eric André. Once we were seated, in orchestra left, the festival’s artistic director, Dennis Lim, began speaking to us from the stage. “Everything about The Curse screams cinema to me,” he said, by way of explaining why exactly NYFF had decided to screen several episodes of television. (The remaining seven episodes will be shown at Film at Lincoln Center in chunks, starting later this month.) “Emma Stone,” he continued, “is not just one of the best actresses of her generation but one of the bravest,” possibly in reference to the time she played an Asian American woman in a movie called Aloha (2015). In The Curse, her character, Whitney—the daughter of an eviction-happy slumlord—is the cohost of an HGTV-style show in development, Flipanthropy, on which she and her husband, Asher (Nathan Fielder), convert foreclosed buildings in a small New Mexico town into carbon-neutral reflective-glass Passive Houses and subsidize rent, sort of, for the local community. Asher is the official recipient of the titular hex, after he gives a little girl (Hikmah Warsame) selling soda in a parking lot a hundred-dollar bill (it’s all he has in his wallet!) for some good-Samaritan B-roll and then, when he thinks the cameras have stopped rolling, asks for it back. “I curse you!” she says—a TikTok trend he takes for black magic. When Whitney finds out, she—the head on the other side of the white-guilt coin—panics, telling Asher they need to find the girl and repent so that Flipanthropy’s “good karma” can be restored. Together, they also attempt to avoid a news reporter’s probing questions; court a local Native artist, hoping she’ll agree to serve as their cultural sensitivity consultant; try to conceive a child, even though or maybe because Asher, like Whitney’s father, has a penis approximately the size of a cherry tomato; while they’re having sex, with Asher fully clothed and kneeling at the foot of the bed with a vibrator, address an imaginary man named Steven (only he can give Asher permission to come); open a café called Barrier Coffee that is supposed to offer jobs to locals but instead exclusively employs people with Australian accents; celebrate Jewish holidays, since Whitney has recently converted. Nothing about it felt especially brave, and we agreed that, taken on their own, the first three episodes don’t really go beyond bloodless self-parody. There’s something of an awkward power struggle between Safdie’s penchant for oversaturation and Fielder’s abject earnestness—together they pack in so much stuff that Whitney and Asher, even as self-abasing caricatures, end up feeling mostly unspecific. But there are some real signs of life in the third episode, including a scene in their bedroom in which the two engage in a giggly protracted struggle to remove a tight sweater that Whitney is wearing and, at her insistence, attempt and fail to re-create the moment for an Instagram video (“This is so us!”). It’s almost touching to see them have fun together, and to see their efforts quickly devolve into desperation and anger at not being able to summon it again. When they learn that the family from the parking lot has been squatting unknowingly in one of their properties, there’s another suggestion that a shift in power or perspective, or the introduction of a new dynamic, might be in store. But by this point it was almost midnight, and we were so hungry. When we got out, we headed to the twenty-four-hour Flame Diner on Ninth Avenue. They’d replaced the reflective-Helvetica menus we’d been so fond of with a design that felt truly timeless.

Left: September 23, 2023; Right: October 12, 2023.

—Amanda Gersten, associate editor, and Oriana Ullman, assistant editor

The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed (2023).

Joanna Arnow’s first feature, The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed, which she wrote, directed, edited, and stars in, is an appropriately scalding portrait of the way many of us live now. Her character, Ann, is working a corporate job with the baroque pointlessness of an I Think You Should Leave sketch, but without the cleansing outbursts of manic rage. She’s in a sub/dom relationship with an affectless older man (Scott Cohen) who has to be badgered into bossing her around. Her parents (played by Arnow’s own parents) are adorable but maddening; the most moving moment of the film might be her father’s impassioned, despairing rendition of “There Is Power in a Union,” presented without further comment. On the basis of the film’s subject matter, I expected something intimate and loose, in the tradition of Lena Dunham’s Tiny Furniture, or of its great forerunner Girlfriends, directed by Claudia Weill. Instead, Arnow’s film has the bleak, intentionally alienating precision of Roy Andersson’s existential vignettes, the scenes linked by sensibility and the relentless pursuit of deadpan punch lines rather than narrative momentum. The discomfort in the auditorium was palpable during a scene in which Arnow is costumed and gagged as a “fuck pig,” among other degradations, though a bit in which she slowly rolls away from her boyfriend in bed after he admits he’s a Zionist drew startled, knowing laughter. Without putting too fine a point on it, the film proposes a relationship between the forced humiliation of contemporary work and the slightly more freely chosen one of romantic relationships. Does the hopelessness of one’s professional future engender a concurrent longing for sexual abasement? Maybe, for a generation steeped in gig work and screen-mediated social anomie, it’s kind of all just the same thing.

—Andrew Martin, editor at large

Priscilla (2023).

Sofia Coppola’s Elvis is soooooo hot. Hotter even than Robert Pattinson as a vampire, and so bad; hotter and, in a way, badder than Christian Bale as a serial killer. The fact that Jacob Elordi (the evil quarterback from Euphoria) is so insanely hot and good at throwing chairs is definitely the best part of Priscilla—and its biggest problem. The thing about Priscilla Presley, Elvis’s young bride and Coppola’s heroine, is that she just wasn’t all that hot, or charismatic, or complex, or talented. Cailee Spaeny’s most interesting attribute, playing opposite Elordi (6’5″), is her height (5’1″). That sixteen-inch differential might be the film’s only real source of tension, both visually (the slow shots of Graceland at golden hour get old quickly) and emotionally. Though both are wonderful actors, the script—which tells the story of a fourteen-year-old fan’s abusive marriage to her pop-star idol—gives Spaeny and Elordi little beyond the kind of canned married-to-a-bad-man plotline of which there are as many examples in media as there are Elvis impersonators in Vegas: both the drug-addled King of Rock and the doe-eyed Priscilla are little more than a progression of convincingly inhabited costumes.

Even a boring woman deserves a life of her own, but does she deserve a biopic? This is, to Coppola’s credit, an interesting aesthetic problem: a question of finding a force to counter a fundamental imbalance—in age, sure, but also in magnetism and narrative agency. Priscilla’s half-hearted attempts at self-assertion do little, dramatically. A better answer might have been found in Priscilla’s passion for passivity, a love that could easily have been as willful and perverse as her husband’s cruelty and carelessness were pathetic. But Coppola doesn’t let the driving force behind the real Priscilla’s life—her submission to desire—drive her story; in fact, no one seems to be driving here at all. We get a two-hour movie with as little movement as a dollhouse, and a woman as cinematically inert as that metaphor suggests.

At the age when Priscilla met Elvis, I loved Lost in Translation, Marie Antoinette, and The Virgin Suicides in a way that I rarely love anything now. Rather than teaching me the joys of emancipated, divorced adult womanhood (or midcareer female filmmaking), Priscilla did the opposite: this tale of a teenage crush gone on too long mostly made me yearn for a time when I found it easier to lose myself in fantasy. And for Jacob Elordi to punch the wall again. One has the sense that Coppola feels the same way.

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor