In 2016, I attended Artangel’s ‘Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison’ exhibition, which took as its departing point the incarceration of Oscar Wilde for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895. As part of a series of readings and tours, famous artists, writers, and public figures were invited to recite sections of De Profundis (1905) – a letter written by Wilde from prison to his former lover Lord Alfred Douglas, published after his death. I wrote about this experience in my book Ethical Portraits: In Search of Representational Justice (2021), and years later I still think of the exhibition often, particularly when re-evaluating art’s role in justice, representation and rehabilitation. .

Lynette Newson, Correctional Institute for Women, Corona, California from Alyse Emdur’s Prison Landscapes (2023). Courtesy the artist

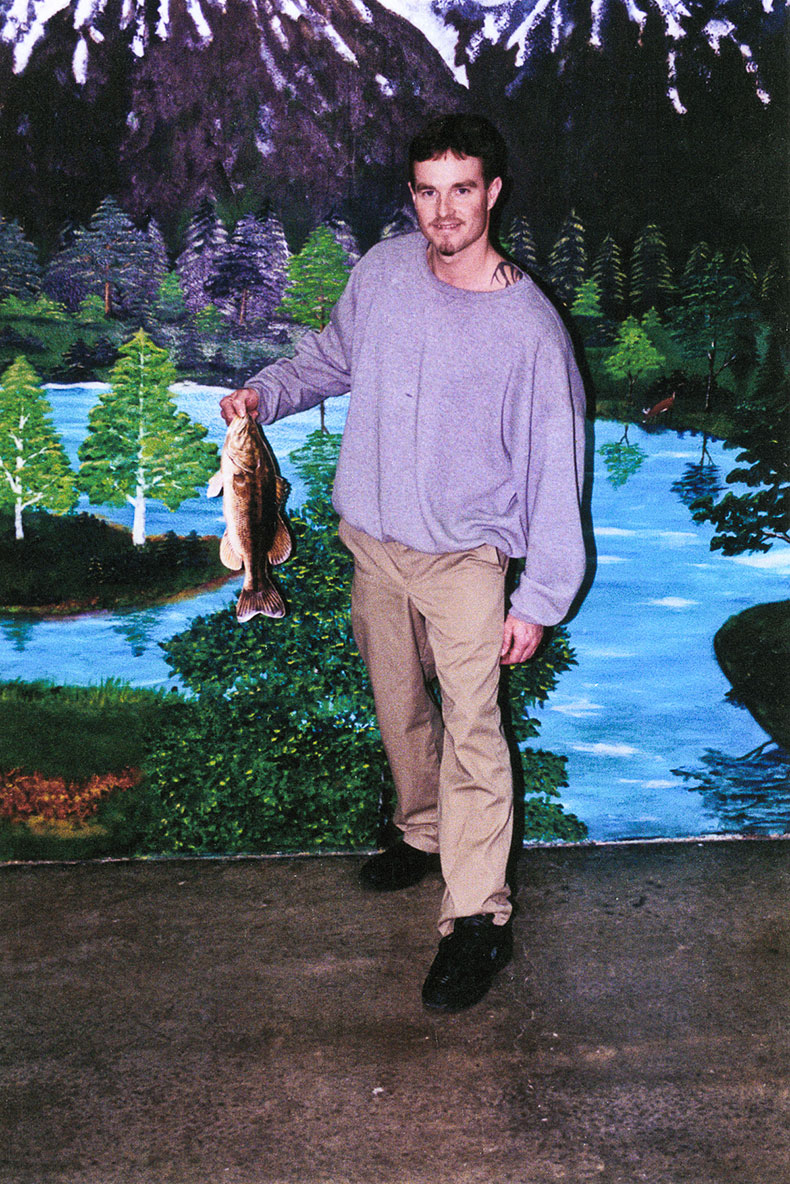

It also made me ask: what does prison art produce therapeutically? Theories of restorative justice, community accountability and rehabilitation have been further questioned within the fields of critical prison studies and abolition in recent years. Art has the radical potential to create new worlds for the dispossessed allowing them to transcend physical confinement into into the realms of imagination. Alyse Emdur’s Prison Landscapes project documents this vividly. The project, which started in 2005 and was published as a book in 2013, gathers together 100 photographs of inmates standing in front of backdrops painted by the prisoners in visitation rooms, the purpose being that family members can have an image of them not solely defined by prison walls and aesthetics. As such, Emdur’s art permits a sense of cognitive dreaming, where the imagination is allowed to take on its own life and world.

James Bowlin, United States Penitentiary, Marion, Illinois from Alyse Emdur’s Prison Landscapes (2023). Courtesy the artist

Dreaming is similarly raised by the Koestler, a prison charity which helps ex-offenders express themselves creatively. They suggest that artistic outlets are fundamental to rehabilitation: ‘Engaging with art and creativity can help prisoners to learn new skills and gain the confidence to live positive and productive lives, helping them on their rehabilitative journeys.’

Walls divide, sanction and separate: prisons are designed to both act as a form of ‘out of mind’ and as a heavily surveilled space. This also implicates the art and representation we see in the mainstream media and the narratives we are told about the lives of inmates specifically. Mugshots, criminal e-fits and courtroom sketches are all created and disrupted publicly from a biased position – one which often favours further criminalising those who are incarcerated. Both representations outside and inside prisons cultivate a narrative grounded in the removal of agency on behalf of the prisoners. In turn, art created from within prison has the capacity to reimagine, change and alter perceptions of the inside on the outside. There have been several other projects across the United Kingdom in recent years which have grappled with the complexity of art’s ethical and rehabilitative potential. The intersection of class and socio-political and economic issues also relate to art’s history predominantly being for the middle and upper classes, for those in positions of power and prestige. The justice system gives the impression that to create art would be to transgress this privilege, that therapeutic creativity is moving away from discipline and punishment.

Dean Kelland working in his studio HMP Grendon. Photo: courtesy IKON Gallery

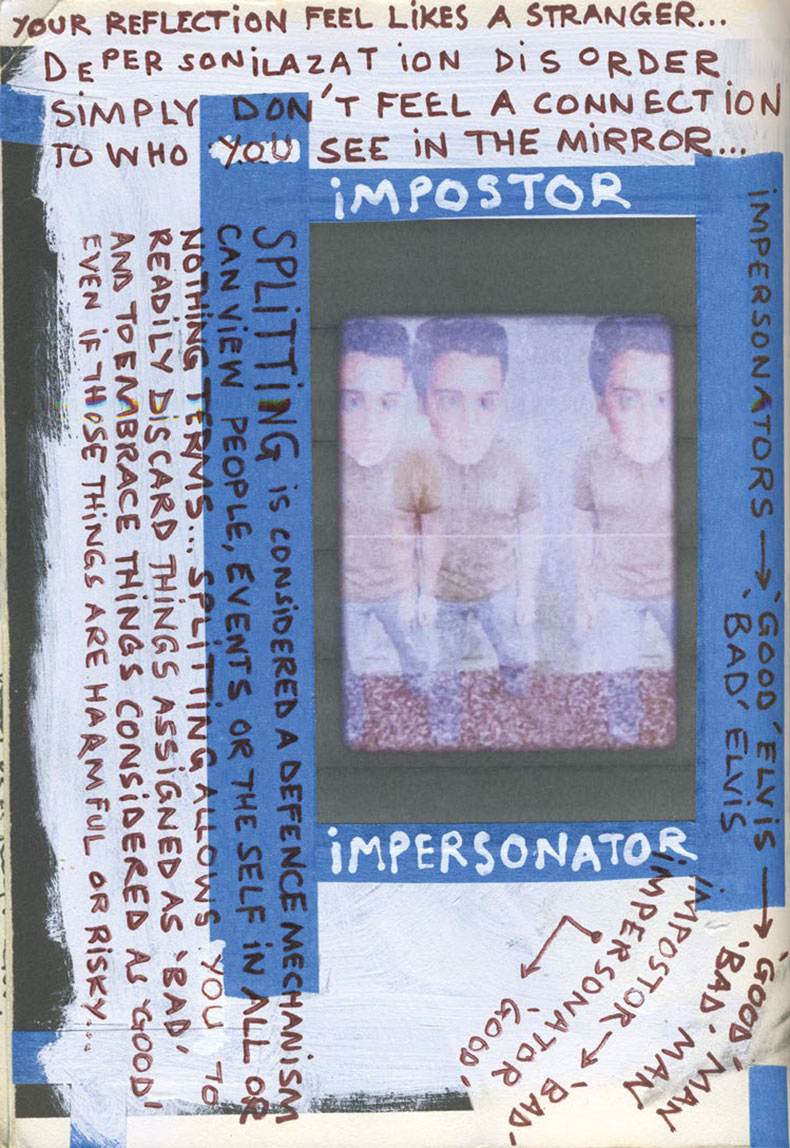

At IKON Gallery in Birmingham there is currently an exhibition by the artist Dean Kelland titled ‘Imposter Syndrome’ that explores some of these issues of creativity in prisons. During a four-year residency (2019–23), Kelland made art at HMP Grendon, an all-male, Category B therapeutic prison. The nature of this residency, of residing within a prison and exploring the multiplicities of the artist’s own identity and questions of masculinity more broadly, returns to the question of who gets to speak and create while incarcerated. Much like some of the issues around cultural capital and appropriate production, Kelland reinstates the ongoing question of carceral realism. Carceral realism, his work demonstrates, is the boundary between the very real challenges of running a therapeutic programme in prisons – where inmates often do not even have access to basic art materials – and art therapy as a vital act of truly understanding the nature of offending. For instance, in his film Catch Back the Breeze (2022), Kelland portrays men as having their agency undone by the prison system, unable to challenge their image to the outside. The realism here is both felt in its documentation of the grey walls inside HMP Grendon, making the case for art therapy, colour and creativity, all the more pertinent. Indeed, HMP Grendon has some of the lowest reoffending statistics in the country. It offers group therapy and structured community living, integrating prisoners in the day-to-day decision making as to how things should be run, for the better.

Much like the romanticisation of celebrities who end up in prison, or are somehow tied to the justice system, Kelland makes visible the disparities in this form of representation and what needs to stand in its place for most prisoners – the chance to represent themselves. In relation to art therapy, this could mean documenting the experience as being conducive to representing masculinity differently, or the psychological impact of being incarcerated. From the outside, we are cut off from accessing the experience of prisoners, and therefore their representation to the general public is hindered and influenced by what the media chooses to portray. The art exhibited at IKON Gallery undoes some of those disparities.

Sketchbook image (2023), Dean Kelland. Photo: courtesy the artist

Across these projects, artists and incentives, a conclusion about rehabilitation is not reached but instead posed as an ongoing sense of survivability and necessity. Because to be seen, to be represented and to find a creative outlet is one of the most humanising tools there is.

Hatty Nestor’s writing has been published in Frieze, Granta, The White Review and other publications. Ethical Portraits: In Search of Representational Justice (2021) is published by Zero Books.