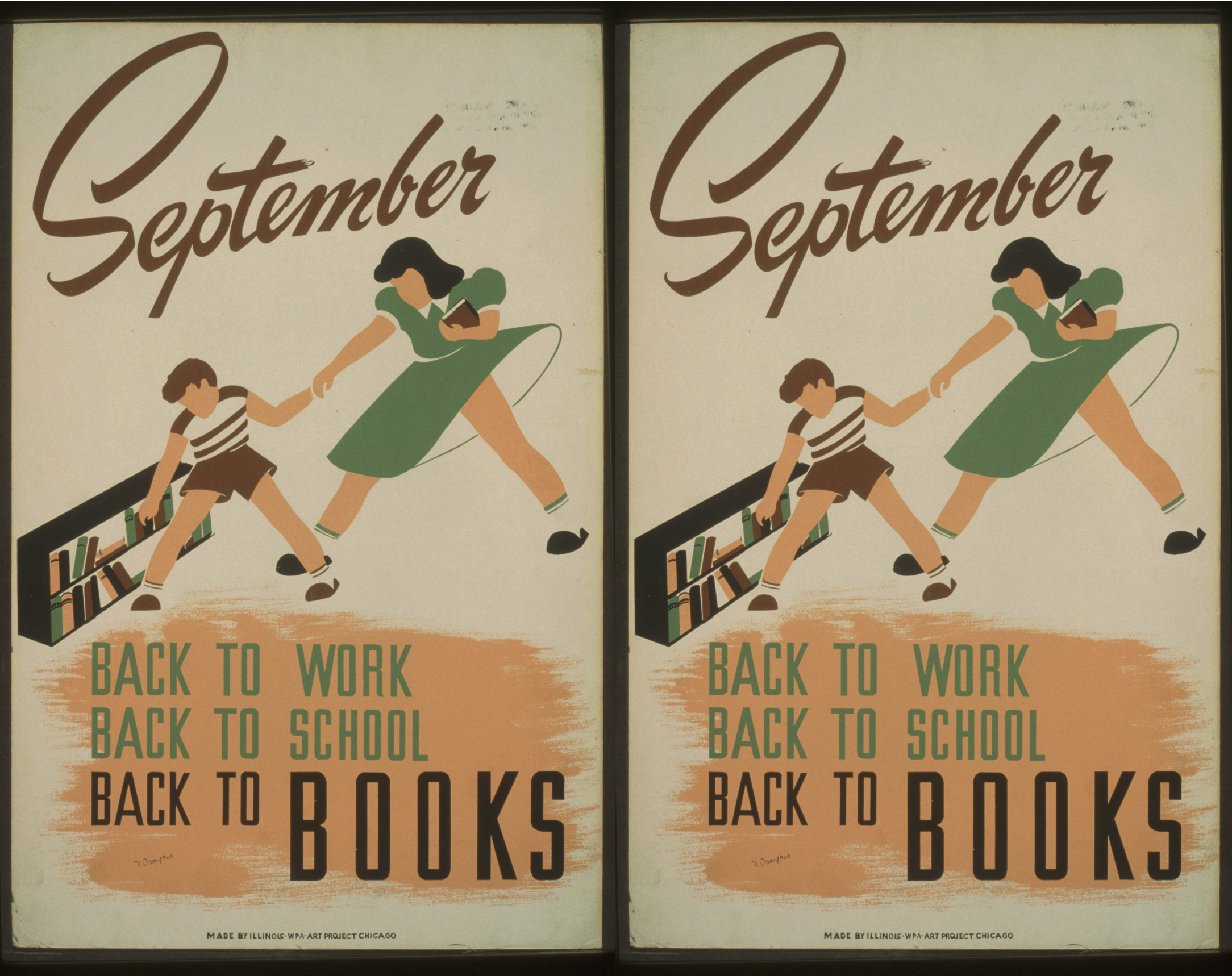

Work Projects Administration Poster Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Pick up Chloe Aridjis’s Dialogue with a Somnambulist and open it somewhere shy of halfway and find a piece of writing called “Nail – Poem – Suit.” It is only one page long. Read it. Ask yourself what it is that you just read. A story? A prose poem? An essay? A portrait? When is the last time you couldn’t quite answer that question when confronted with a piece of contemporary writing? In our world of literary hyperprofessionalization it is not a question that comes up very often, and you may have to reach back into literary history to remember the writers who once provoked a similar uncertainty in you. Writers like Borges, writers like Kafka. Or even further back, to the undefinable and uncontainable prose of Thomas Browne’s Urn Burial, or those slivers of Sappho. Writers who thought of language as painters think of paint: not as means to an end but as the precious thing in itself.

Within this single page of Chloe’s three things collide—that nail, a poem, a suit—and all within one man’s consciousness, although this consciousness is rendered externally, by a voice that comes from who knows where. But describing Chloe is hard: Why not read the whole thing for yourself, right now?

A man walks down the street trying to recollect the final lines of an unfinished poem he had been composing two nights ago when the phone rang. It was his seventy-four-year-old mother calling to remind him of the suit she’d ordered for his birthday, now ready for collection at the tailor’s, although it was likely alterations would have to be made. He reaches the corner and treads on a large corrugated nail that goes rolling off the pavement and into the street. The man’s first thought is that this nail has fallen out from somewhere inside him; his second thought is that it dropped out of the woman wheeling a bicycle a few metres ahead. His third thought is that the nail fell out of the teenager with the pierced lip who delivers the post each morning. Unable to draw any conclusions, the man casts one final glance at the nail now lying parallel to the tire of a parked car and returns to the matter of the unfinished poem, which, should he ever complete it, will surely fit him better than the tailor-made suit.

What I love about Chloe’s work is the way it stages a series of rejections. It is not especially psychological. (The man does not think the nail has fallen out from inside him.) Nor is it overly obsessed with what we might call the relational. (The man does not think that the woman dropped the nail.) It rejects sociological generalizations. (The man does not think that the nail is the fault of this generation, or the internet, or “the way we live now.”) It is also beautiful. It sits like a jewel in your mind. It is not in the business of offering the reader prefabricated conclusions about the nature of social reality presented in the overfamiliar language of journalism, activism, or advertising. It is refreshingly unbound to any temporal sense of necessity. Chloe’s writing matters not because its topics are ripped from today’s headlines but because she is trying to illuminate this world using only words. The politics of her prose is existential rather than anecdotal, as it was with Kafka’s. In what way can a human being be made to feel like a bug? asks Kafka. What’s more significant in a person’s life? asks Chloe. Events, ideas or things? Nails, poems, or suits? And the single-minded search for words that “will surely fit”—better than any template or tailored suit—is what animates every page of this wonderful book.

—Zadie Smith

A friend in London handed me a copy of Kate Briggs’s The Long Form as I was about to board a plane, and I quickly read a hundred and fifty pages in the air. Over the next week or so the book bled into my dreams and my consciousness; I could think of almost nothing else but this story of a young single mother and her newborn, both in a desperate quest for sleep. There is a fly-on-the-wall quality to the prose, which sustains a quasi-verité account of the derangement (and joy) of new motherhood, whereby we imagine a story composed in real time, its author holding the baby in one arm and writing with the other. The Long Form is also an exhilarating experiment in form, an examination of the function of time in the novel, which includes an irresistible graphic element that punctuates the narrative and helps to conjure the stagelike setting occupied by the maternal dyad. Briggs invokes E. M. Forster—“Every novel needs a clock”—and indeed her novel’s timepiece has us on the edge of our seat, turning the pages in anticipation. I finished The Long Form and started again from the beginning; I wanted to understand how this miracle of a book had come to be; I was not ready to let go.

—Moyra Davey

Last month, I picked up Grand Tour by Elisa Gonzalez, a debut poetry collection out next week. Together, the poems have the quality of a diary whose pages have been scrambled. Time moves according to its own logic, sometimes conflicting with the body moving through it. Someone is always leaving, arriving. The poems stake out beginnings and endings almost obsessively, but then fail to oblige them. Mother, father, sister, brother: the relations are cyclical, slippery, each person moving in and out of the thing they represent. In “The Night Before I Leave Home,” Gonzalez writes:

My brother turns to me near sunrise

to ask, What do you think he’s doing? Right now?And I spin a story of a father

waking to polish his teeth, spit blood

into the eye of a porcelain bowl, wash a face like my brother’s.That was a game, yes, us seeking the man

he was when not hurting us one and then the other,

and then the game ended

It’s so easy to read poems too quickly. But I’ve been trying to return to these periodically, spontaneously, when I’m not so desperately seeking plot—though they contain that, too, and more.

—Maya Binyam, advisory editor