Gustave Courbet: The Rebel of the Romantic Movement

Learning the details of an artist’s life — the drama, the struggles, the mundane — can make their history and contributions to art really come alive. Gustave Courbet’s life fits that bill.

Subscribe to Artists Magazine now so you don’t miss any great art instruction, inspiration, and articles like this one.

I loved discovering all the details of how he was heralded as a rebel of the Romantic movement. And, he is now considered one of the first to propel Realism into the modern world. Just imagine! Soak up the story — it’s pretty epic.

Greatness Is Born

Born in 1819, Gustave Courbet emerged from the quiet rural village of Ornans, in the Franche-Comté, to become one of the most famous artists and most provocative characters of 19th-century France. In an era dominated by Romanticism and the still pervasive Neoclassicism, he seized on a new sense of the real in painting. And thus, he is often credited with coining the term “realist.”

Gustave Courbet worked during a time of great social and political change. His paintings reflect the rising power of the masses, the ascendance of a scientific and utilitarian outlook, and the influence of a plethora of artistic and intellectual movements that swept through Paris in the middle of the 19th century and spanned everything from anarchism to symbolism.

But more than anything else, Courbet was simply a painter whose thick tactile surfaces, aided with an aggressive palette-knife technique, gave his pictures a physical presence that was highly innovative, theatrically assertive and completely unique. His direct, and at times almost naïve, approach to painting allowed him to show common people and ordinary events on a scale formerly reserved for visions of gods and kings.

The artist welcomed the arrival of photography, which he was quick to use as reference for his own work. And, his career extended beyond realism to a point where he began to toy with new ideas that would grow into Impressionism.

No Mentor to Name … Truly?

“To tell the truth, I must declare that I have never had a teacher,” Courbet wrote to a newspaper editor in 1851. Like many of the artist’s personal accounts, this was not exactly true. In fact, Courbet’s training as an artist began early in life and extended for some years.

His father, a small landowner, took care to have his son educated and hoped he would enter a solid profession like the law. In his teenage years, however, Courbet became a pupil of the painter Charles Antoine Flajoulot while attending the Royal Academy at Besançon. Flajoulot claimed to have been a pupil of Jacques-Louis David. His admiration of classical draftsmanship was certainly imparted to his young student.

In 1839 Courbet found himself in Paris. Rather than take up the study of law, he set to work in the studio of M. Steuben, a minor painter who took in several students. Courbet also began a long practice of copying masterworks in the Louvre. He frequently painted over previous studies while he worked his way through the Dutch, Flemish and Italian masters, as well as more contemporary works by Ingres and Delacroix.

Salon Style

Courbet spent seven years as an apprentice before achieving any kind of recognition. At the time the only path to a successful career in art was through the official Salon. Held since the late 17th century, the Salon was an annual exhibition, sponsored by the government. Works were vetted by a jury and hung floor to ceiling in huge exhibition halls to be viewed by a fee-paying public.

Gazettes were published in which the critics of the day vented their opinions on the work. In general, the art received a level of scrutiny and passionate discussion that most visual artists would envy today. It was a society in which art mattered. Moreover, the output of painters was seen as an important part of the political and intellectual discourse of the day.

The French government purchased a number of paintings from the Salon each year at fairly hefty prices, to be hung in various public buildings. Any serious art collector would certainly pay close attention to the works offered.

3 Out of 24

Courbet began sending paintings to the Salon almost as soon as he arrived in Paris. Indeed, between 1840 and 1847 he submitted 24 paintings, of which only three were accepted.

The reasons for the artist’s lack of success in these years are fairly obvious. His skills as a draftsman were modest, and his hand was somewhat heavy. What’s more, Courbet had yet to find himself as an artist and his work vacillated between experiments with a romantic style and more direct observation, particularly in his portraiture.

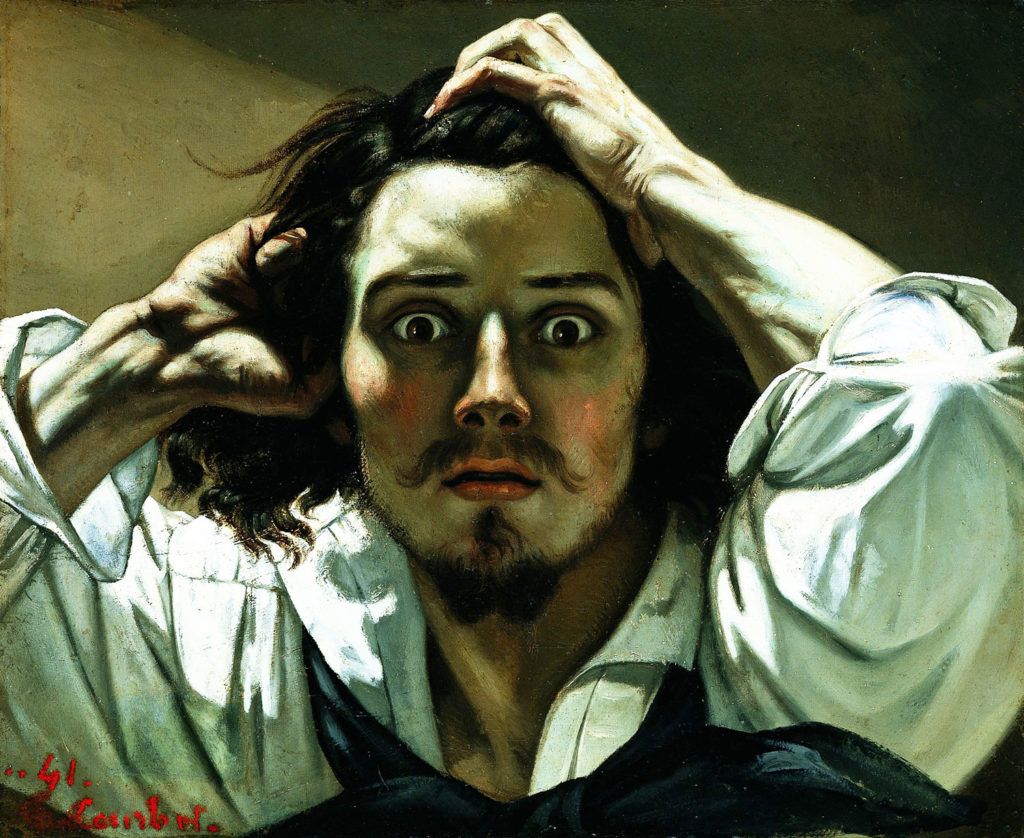

The Desperate Man

One of his more dramatic achievements from these years was The Desperate Man of 1844. Here he shows himself as a lunatic, clawing at his hair, his eyes wide with intensity.

What the work lacks in finesse — in particular in awkward details of rendering in the hands and fabric—it makes up for with theatrical drama brought about by powerfully drawn contours and heavy chiaroscuro.

The Wounded Man

Two years later The Wounded Man finds the artist toying with a romantic look. He imagines himself languishing from a wound suffered in a duel.

Here the heaviness of the rendering and the resulting monumentality of form seem uneasily at odds with the subject matter. This is a subject that calls for the delicate touch of a Fragonard or the flowing brush of Delacroix rather than the lumbering hand and lumpy forms of the young Courbet.

In the meantime, the artist had become immersed in the newly emergent culture of the bohemians. “In our overcivilized society,” he wrote to his friend Francis Wey, “I must lead the life of a savage — I must free myself even from governments. The ordinary people have my sympathies — I must speak to them directly, draw my inspiration from them, find my livelihood from them. Because of that, I have just embarked upon the wandering and independent life of a bohemian.”

Throughout his career, Courbet would insist on his independence as an artist and as a man. His private life involved a long series of romantic liaisons. But he regarded marriage as a bourgeois institution and refused to have anything to do with it.

Big Output

Success began for Courbet when he exhibited no less than 10 paintings at the Salon of 1848 and received enthusiastic notice from Champfleury, a newly influential critic. Champfleury was a champion of a new realism in French art already evident in the novels of Georges Sand. Soon he was prodding Courbet in that direction.

The following year the artist achieved a career breakthrough at the Salon when his painting After Dinner at Ornans was admired by Delacroix and purchased by the state. The picture was an enormous rendering of a simple evening in the country. In the painting, Courbet and his family relax after dinner as one of their number plays a tune on the violin.

The painting is obviously influenced by Dutch painters, such as Rembrandt, Hals, David Teniers and others with whom Courbet had become familiar when he made a trip to Holland in 1846. Writing to a curator in 1850 he said, “All my affinities are with the Northern peoples. I have traveled twice in Belgium and once in Holland for my instruction and I hope to go there again.”

A New Approach

Courbet’s genius was to use a 17th-century Dutch approach to painting everyday life and transfer it to 19th-century rural France on a large scale. This was something radically new for the French public. They generally preferred renderings of country life to be wrapped in a pleasantly distant romance.

Returning to his family home for the winter of 1849 through 1850, Courbet pursued this approach with a vengeance. During this time, he produced his famous painting A Burial at Ornans. Working on a vast scale, he painted a large group of figures as they had appeared the previous year at the burial of his grandfather.

“We must drag art down from its pedestal,” he wrote to a friend that winter, “for too long you have been making art that is pomaded and ‘in good taste.’ For too long painters, even my contemporaries, have based their art on ideas and stereotypes.”

Radical Will Out

Exhibited at the Salon of 1850 through 1851, A Burial at Ornans caused an enormous stir. It was monumentally large and showed in stark frankness the rural society that so many Parisians were anxious to ignore.

The painting was condemned as ugly, and many saw it as politically radical. France, and indeed much of Europe, had been swept by revolutions and social unrest in 1848, all part of the dynamics of industrialization, with its shift of power and wealth along with the rise of an urban society.

Courbet himself never saw his pictures as particularly political. Rather, he seems to have found himself in paint as he tried to represent quite straightforwardly the life he knew best.

Finds His Way

In his Young Ladies of the Village of the following year, it becomes obvious his somewhat heavy hand was then perfectly suited to his task. Something in the coarseness of the handling and the thickness of the paint gives the picture a sense of directness and authority. Also, it gives the scene an aura of honesty that would be hard to project with a more skillful and polished approach.

And if the scale of the cows in the background is at odds with that of the trees, then it only serves as a further guarantee of the artist’s direct and difficult confrontation with nature. We are convinced he only seeks to show us, in a manner devoid of artifice, a simple country moment. A moment for which his sisters bestow a gift of money on a young cowgirl in the fields near his native town.

In 1854 Courbet exhibited yet another masterpiece, The Meeting, or “Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet.” The picture shows the artist meeting his patron Alfred Bruyas on the road near Montpellier in May 1854. But the painting is far more than a simple record of an event. Bruyas was a wealthy banker and art collector who became a big supporter of Courbet. In the painting, however, it is the banker who takes his hat off to the artist while his servant humbly bows. Courbet himself appears to have been walking holding his hat by his side and carrying his traveling easel and paint box on his back. He strides forward with confidence and authority. Again, Courbet’s powerful handling and strong sense of graphic outline has been deployed to great effect. The painting exudes a sense of open directness that is distinctly modern.

Gone is all the measured elegance of Neoclassicism and gone too are any of the trappings of Romanticism. The artist is inviting us to look head-on in stark daylight at a world where the social order has been turned on its head.

One of the Masterpieces

Courbet went on to make a number of large pictures of rural life along the same lines, although none of them ever achieved the same power as A Burial at Ornans. In 1855, however, he produced what is rightly considered one of the great masterpieces of 19th-century art, The Painter’s Studio: A Real Allegory Summing up Seven Years of My Artistic Life.

The picture is a large tableau in which the artist shows himself at work on a landscape in the center of the painting watched by a naked model and a young boy. He is flanked on one side by supporters and figures from his artistic world, including his friend Baudelaire and the poet Max Buchon.

On the other side, is a darker world that Courbet described as “the other world of trivial life, the people, misery, poverty, wealth, the exploited and the exploiters, those who live on death.” Courbet intended the painting to be hung at the International Exhibition of 1855. He was greatly disappointed when the jury rejected it.

However, he did show the work in a temporary structure he had built nearby. He mounted one of the first privately sponsored solo exhibitions in French history. The event was heralded by a sign announcing: “REALISM. G. Courbet: exhibition and sale of 40 pictures and 4 drawings by M. Gustave Courbet.” A pamphlet accompanied the exhibition in which Courbet laid out his artistic principles:

“The title Realist has been imposed on me in the same way as the title Romantic was imposed on the men of 1830. … I simply wanted to draw forth, from a complete acquaintance with tradition, the reasoned and independent consciousness of my own individuality. To know in order to be able to create, that was my idea … to create a living art — that is my goal.”

Among the visitors to the exhibition was Delacroix, who wrote in his journal: “I stay there alone for nearly an hour and discover that the picture of his which they refused [The Painter’s Studio] is a masterpiece; I simply could not tear myself away from the sight of it.”

The Erotic Arts

A number of Courbet’s paintings in the following years are distinctly erotic — or at least suggestive. They often focus on the sexual or romantic relationships. He famously painted a picture of female genitalia for a Turkish collector and his various paintings of pairs of women culminated in The Sleepers, a monumental picture of two naked women entwined in bed.

One of the more sedate paintings on this theme is Young Ladies on the Banks of the Seine, of 1856–1857. To the modern eye, this work is simply a splendidly painted idyll showing two young women relaxing. At the time of its exhibition, however, it caused quite a stir.

Parisians had begun to enjoy leisurely outings along the Seine on weekends. Courbet was one of the first painters to take up this subject matter, which would later become a favorite of the Impressionists. The audience of his day, however, was scandalized by the fact that the young ladies were in a state of dishabille. Although she looks rather overdressed to us, the lady in the foreground is essentially shown in her underwear — a chemise, corset and petticoat. The fact that she still has on her yellow gloves was seen as particularly erotic.

Courbet’s new friend P.J. Proudhon, a critic and anarchist, wrote copiously about the two young ladies who were clearly known to him and saw the picture as a moralistic comment on the state of “kept” women. It is entirely unlikely that the artist himself shared this view. He may simply have enjoyed presenting the public with a provocation. Nothing, however, can detract from the sheer richness of the painting, with its luxuriant fabrics, its wealth of foliage and the dreamy reverie of the ladies themselves.

Whistler’s Friend

As the years progressed into the 1860s, Courbet’s work involved itself in a mass of portraits, landscapes, still lifes, and hunting scenes. The task of the painter, he felt, was to take the world as he found it and to present it straightforwardly, although he often seems to flirt with a certain amount of symbolism.

Always gregarious and avid for new acquaintance, Courbet befriended the young Whistler, fresh in Paris. Whistler came and painted with him for a while. Courbet created a powerful portrait of Whistler’s mistress, Jo, as she combs out her long red hair.

Here the thick paint and great intimacy of the pose transmit a strong sense of sexuality. Courbet’s landscapes also became increasingly monumental, and it is hard not to read them as symbolic in some way.

His painting The Wave reduces sea and sky to a powerfully simple format suggesting the subject is symbolic of the power of nature itself. Using increasingly open brush- and palette-knife work, the artist continually drew attention to the physical nature of painting. He also prepared the way for the Impressionists, who would use a broken paint surface to recreate the effects of light.

Politics Aside

Insisting on his own independence as an artist, Courbet’s political views were always loosely held. He liked to claim he was on the side of the people, a socialist. But in a world before Marx, he never saw politics in terms of a class struggle. Nor was he averse to becoming a minor capitalist himself. When he made money he used some of it to purchase land in his hometown, and he invested in railroad shares. Moreover, he was highly desirous of public success and much of his correspondence involves intrigues to get work shown or purchased at the Salon.

A very public figure and tireless self-promoter, he was notorious for engaging in voluble and furious arguments about his work in the various cafés and brasseries where artists congregated in Paris. He was delighted when his hunting paintings began to enjoy wide acclaim among the upper class and aristocratic patrons of the arts.

Summering in fashionable Trouville in 1865, he boasted in a letter to a friend, “I am painting the prettiest women at Trouville — I have already done a portrait of the Hungarian countess Karoly, and it is a tremendous success. Over 400 ladies came to see it and nine or ten of the most beautiful want me to paint them too. … I am gaining a matchless reputation as a portrait painter.”

A Revolution Ends It

It is curious, that in spite of the artist’s clear delight in his success with smart society, he came undone over a revolution. In 1871, following the chaos of the Franco-Prussian War, the Paris mob declared a commune and seized the center of the city. Courbet joined enthusiastically and was quickly put in charge of securing the city’s art treasures. Gripped with a revolutionary fervor, he went along with a proposal that the column in the Place Vendôme, a sort of distant cousin of Trajan’s Column commemorating the triumphs of Napoleon, be dismantled.

The commune survived for only two months, however. And, when the army finally took charge after a bloody fight, Courbet was imprisoned for six months. Worse, the French government held him responsible for the destruction of the Vendôme column. And in 1873, the government ordered him to pay the costs of restoring it.

Faced with bankruptcy and further imprisonment, the artist fled to Switzerland. From there he conducted negotiations with the French government. These talks eventually resulted in a rather bizarre payment scheme under which the artist would make monthly payments for the next 30 years. But Courbet was ailing. The years of bohemian living, heavy drinking and the stress of prison had taken their toll. He died in Switzerland, exiled and close to bankrupt, in 1877.

Article contributions by John Parks. This article was originally posted in 2018. Updated in September 2023.

Do you have any interesting facts to add about Gustave Courbet? Share them in the comments!

Enjoying this article? Sign up for our newsletter!