Patricia Highsmith (from Loving Highsmith, 2022).

DB here:

Crime fiction, whether in words or pictures, is a bigger category than we might initially think. There are whodunits, hardboiled detective stories, police procedurals, suspense thrillers, and stories of gangsters, professional crooks, and petty scoundrels (e.g., Elmore Leonard’s world). That’s a lot in itself. But since every plot of any interest depends on some disruption of a stable situation, an illegal transgression can do the trick. So we can get bank robbery in a comedy (e.g., Take the Money and Run, 1969), or murder and extortion in a family melodrama (The Little Foxes, play 1939, film 1941), or authorial disputes about plagiarism (Secret Window, 2004). Even romantic comedy has room for a crime or two (Date Night, 2010).

Geoffrey O’Brien is a polymath. He’s written poetry, evocative memoirs (Sonata for Jukebox, 2004), experimental fiction (the recent lyrical “fantasia,” Arabian Nights of 1934), and outstanding literary and film criticism (Castaways of the Image Planet, 2002). He’s also an expert in crime fiction (Hardboiled America, 1997), so he’s ideal for editing the new Library of America collection Crime Novels of the 1960s. His choices, all unimpeachable, cover a lot of the central creative options. There are crook stories, suspense thrillers, a police procedural, several strains of whodunit, psychological studies, and at least one crime novel possibly lacking a crime. In style they vary between pitiless hardboiled narration and more delicate but still forceful dissection of middle-class mores. As you might expect from books of their era, racial prejudice, urban upheavals, and the folkways of the counterculture are seldom far away.

Geoffrey O’Brien is a polymath. He’s written poetry, evocative memoirs (Sonata for Jukebox, 2004), experimental fiction (the recent lyrical “fantasia,” Arabian Nights of 1934), and outstanding literary and film criticism (Castaways of the Image Planet, 2002). He’s also an expert in crime fiction (Hardboiled America, 1997), so he’s ideal for editing the new Library of America collection Crime Novels of the 1960s. His choices, all unimpeachable, cover a lot of the central creative options. There are crook stories, suspense thrillers, a police procedural, several strains of whodunit, psychological studies, and at least one crime novel possibly lacking a crime. In style they vary between pitiless hardboiled narration and more delicate but still forceful dissection of middle-class mores. As you might expect from books of their era, racial prejudice, urban upheavals, and the folkways of the counterculture are seldom far away.

Taking pulp mainstream

The nightmarish plots and staccato vernacular of O’Brien’s hardboiled sampling are vestiges of the pulp magazines, where Hammett and Chandler developed their technique in the 1920s and 1930s. But the classic crime pulps were long gone by the 1960s. What replaced them were the massive paperback originals pouring from presses from the Forties onward. A first paperback printing of a novel would routinely run to 150,000 copies. The success of cheap reprints of hardcover titles impelled publishers to capitalize on the new market with novels written specifically for paperback distribution. The most popular genre was crime fiction. Originals tended to be short, running 60,000 to 80,000 words, with plenty of blank space for laconic dialogues. A dedicated pro could turn out one in a month or two, at a fee of a few hundred dollars.

A vivid example in this collection is Dan J. Marlowe’s The Name of the Game Is Death, which first appeared as a Fawcett Gold Medal paperback in 1962. It starts with three thieves executing a bank robbery. The opening plunges us into the crossfire of pulp narration.

A vivid example in this collection is Dan J. Marlowe’s The Name of the Game Is Death, which first appeared as a Fawcett Gold Medal paperback in 1962. It starts with three thieves executing a bank robbery. The opening plunges us into the crossfire of pulp narration.

Bunny went through the front door in a sliding skid. The kid took one look at my face and started to run back in front of the Olds. Across the street something went ker-blam!! The kid whinnied like a horse with the colic. He ran in a circle for three seconds and then fell down in front of the Olds, his white cottom gloves in the dirty street and his legs still on the sidewalk. The left side of his head was gone.

Bunny dropped the sack and scrambled for the wheel. I was halfway into the back seat when I heard the car stall out as he tried to give it gas too fast. It was quite a feeling. I backed out again and faced the bank, tried to have eyes in the back of my head for the unseen shotgunner across the street, and listened to Bunny mash down on the starter. The motor caught, finally. I breathed again, but a fat guard galloped out the bank’s front doors, his gun hand high over his head.

I swear both his feet were off the ground when he fired at me.

Bunny flees with most of the loot, and our nameless narrator escapes alone. He waits for news that Bunny has found sanctuary and is ready to divide the take. When the narrator hears nothing, he worries that Bunny is in trouble and sets out to find him. In his travels from Phoenix to Florida he encounters several problems that demand violent solutions. Across his trip, it becomes evident that our protagonist is a borderline sociopath.

His journey gives Marlowe’s plot a linear trajectory that is studded with flashbacks to his childhood, including a traumatic incident with his beloved cat. The episodes build a degree of understanding of his damaged personality, only to have that mitigated by a savage climax. Hardboiled to the end.

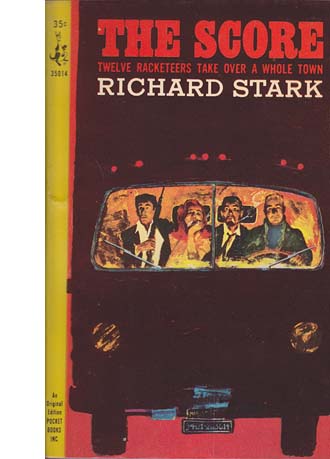

Donald E. Westlake, a favorite of this blog, was endlessly prolific, cranking out erotica, science fiction, comic fiction, psychological thrillers, and hard-core crime stories under several pseudonyms. He created two long-running series, both based on heist plots. A comic one centered on John Dortmunder, a hapless down-at-heel thief. The other series was dead serious (though with some light touches) focused on Parker, an impassive, nearly amoral robber specializing in organizing big capers. The Score (1964) is one of Parker’s most ambitious projects. With a large team, he ransacks an entire town.

Donald E. Westlake, a favorite of this blog, was endlessly prolific, cranking out erotica, science fiction, comic fiction, psychological thrillers, and hard-core crime stories under several pseudonyms. He created two long-running series, both based on heist plots. A comic one centered on John Dortmunder, a hapless down-at-heel thief. The other series was dead serious (though with some light touches) focused on Parker, an impassive, nearly amoral robber specializing in organizing big capers. The Score (1964) is one of Parker’s most ambitious projects. With a large team, he ransacks an entire town.

Westlake broke nearly all his Parker novels into four parts, and within them he enjoyed mixing flashbacks and shifting viewpoints. Part 3 of The Score is a virtuoso panorama of the entire raid, played out in short scenes in different parts of town. It provides a careful layout of how the takeover is engineered. Most scenes are devoted to the robber in charge and provide us characterization that enlivens the action. As usual, the perfect heist goes badly wrong, and Westlake’s anatomy of the scheme forces us to admire its precision up until the final catastrophe.

Westlake exemplifies how the hardboiled tradition could be exciting without being sensationalistic. Avoiding the near-hysteria of Marlowe (no double exclamation points here) and the florid metaphors of Chandler, Westlake is close to Hammett in his understated but elegant style. He playfully references books and movies, as when Parker’s colleague Grofield imagines his thieving days as a long film with a musical score and swooping camera angles. I devoted a chapter of Perplexing Plots to the rigorous intricacy and captivating style of the Parker books. (For online instances, go here and here.)

Hitchcock and Evan Hunter (Ed McBain), who wrote the screenplay for The Birds.

The Score was a paperback original for Pocket Books, which also initiated Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct series. McBain’s police procedurals mixed a realistic treatment of procedures (printed-out lab reports, fingerprint files, and the like) with a slangy dialogue redolent of the hardboiled pulps. Doll (1965) includes not only a gory murder but a series of punishing scenes in which a killer repeatedly injects a captive cop with heroin.

McBain sought to capture the protocols of investigation through the “conglomerate hero” formed by an entire squad. Although Steve Carella is the first among equals, inquiries get split up among his colleagues. In Doll Carella is reluctantly partnered with the troubled Bert Kling. But Carella soon disappears and is believed dead. Kling continues solo until he’s replaced by Meyer Meyer, who’s aided by colleagues Hal Willis and Arthur Brown. Eventually Kling rejoins the hunt and partners with Meyer to resolve the case. In other books, cases run in parallel or are revealed as connected. This sort of plotting, popularized in Hill Street Blues, is common in modern procedurals. McBain complained that others swiped his idea.

Another McBain innovation was an intrusive authorial voice. The action is typically recounted in the third person and through shifting viewpoints in a moving-spotlight manner, but the narration injects digressions and ventures into sheer chattiness. The opening of Doll interrupts the scene of a grisly murder with a lengthy reflection on how police cope with unimaginable crime scenes. This meditation isn’t attributed to Carella or anyone else. McBain, who was an English major in college, deliberately flouted the demand for neutral narration.

I know that in these books I frequently commit the unpardonable sin of author intrusion. Somebody will suddenly start talking or thinking or commenting and it won’t be any of the cops or crooks, it’ll just be this faceless, anonymous “someone” sticking his nose into the proceedings. Sorry. That’s me. Or rather, it’s Ed McBain.

McBain’s string of police procedurals quickly graduated to hardcover publication by Delacorte Press. His success exemplifies the new respectability of the pulp tradition.

The insanely prolific Fredric Brown gets some respectful mentions in Perplexing Plots for eccentric experiments like The Far Cry (1951). Echoes of the hardboiled school show up more mutedly in his The Murderers (1961). The protagonist, a shiftless would-be actor, drifts through Hollywood trying to pick up commercial gigs or small parts in an ongoing TV series. Mostly he’s interested in drinking and hanging out with hippies and pliable women. He gets attached to a businessman’s wife, and together they fumble into a murder scheme. There’s more than a passing resemblance to Double Indemnity, and the hero is a softer, semi-comic descendant of James M. Cain’s doomed fools for passion. Overall, Brown presents a cooler, more laid-back vision of Cain’s sunbaked California car culture and killing fields. As a bonus, Brown merges his murder scheme with another swiped ingeniously from the most prominent woman writer of psychological thrillers.

Murder with gravity

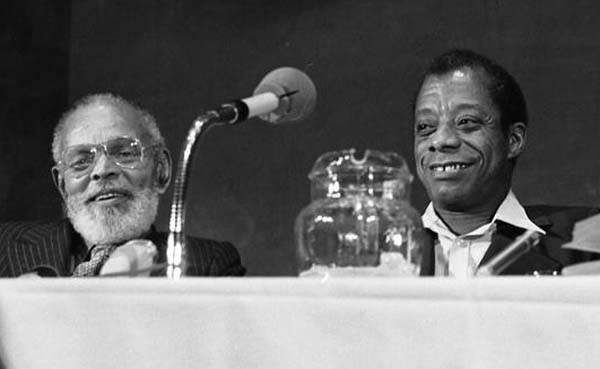

Chester Himes and James Baldwin, 1973. From Stars and Stripes.

Late one night a drunken, psychopathic cop shoots and kills a restaurant’s two kitchen cleaners. A third man witnesses the crimes and escapes. The cop uses all the authority of the law to pursue him. Moving-spotlight narration switches us rapidly from one man to the other as the tension builds and the cop closes in.

Sounds like pure pulp, no?

What if the cop is a racist, and his two victims and third target are Black?

That’s the premise of Chester Himes’ Run Man Run (1966). Himes was one of several Black artists and writers who found sanctuary in Paris after confronting postwar bigotry at home. He won fame in France, and belatedly in the U.S., with a series of hardboiled detective novels (some as paperback originals) centering on Gravedigger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson. The best-known is Cotton Comes to Harlem (1966), which also became a lively movie.

His marquee cops are absent from Run Man Run, but the book is filled out by evocative descriptions of the Harlem milieu and sharp portrayals of the secondary characters, particularly the pursued man’s morally equivocal girlfriend and a cop who’s not as racist as his peers. The density of detail and the psychological probing of hunter and hunted give the book the gravity of a “serious” novel like Himes’ excellent If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945).

Gravity of a comparable sort dominates Charles Williams’ Dead Calm (1963). The situation merges two long-lasting schemas: the woman menaced by the sociopathic killer, and the man trapped aboard a sinking ship. A couple honeymooning in a yacht come to the aid of an apparent castaway and get far more than they expected. Williams gives unremitting apprehension by crosscutting the two situations while also filling in the backstory in ways that add layers of understanding and misunderstanding. It’s a model blend of mystery and suspense.

It’s also a lesson in another, frequently forgotten side of the hardboiled tradition. The tough guy isn’t just a mindless thug; he’s often the master of a delicate craft. Stark’s Parker is a virtuoso in breaking and entering, but also in calmly managing the problems that come up. He works with his hands but also his mind. So does the central male of Dead Calm. John Ingram must draw on his expertise in professional sailing to stay alive in a crisis, and Williams freely lets us understand the minutiae of survival to make us admire his resourcefulness. More significant, Ingram’s wife has absorbed many of the same skills, and her shrewd use of them renders her as no less tough an adversary.

Williams’ rich vocabulary yields the pleasure of watching neat, efficient intelligence in a crisis. Another sort of literary gravity, then, makes this book as evocative as any piece of straight fiction, and more gripping than most. No wonder that Philip Noyce and Terry Hayes were able to adapt it to the screen in 1989 with trim economy.

Ladies of crime

Women writers have been prominent in crime fiction virtually from the start. Anna Katherine Green’s bestselling detective story The Leavenworth Case (1878) predates Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series. Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Marjorie Allingham and others became famous for their mystery novels. In the 1930s and 1940s, Charlotte Armstrong, Elizabeth Sanxay Holding, Vera Caspary, and many others contributed both whodunits and psychological thrillers. Sarah Weinman has collected some of these authors’ outstanding suspense novels in a fine Library of America set, which I discuss in another entry.

Among these admirable artisans was Dorothy B. Hughes, whose Ride the Pink Horse (1946) and In a Lonely Place (1947) were adapted to films that became prime examples of what was later called film noir. Hughes also wrote a discerning critical biography of Erle Stanley Gardner. She reflected thoughtfully on the conventions of crime fiction, reviewing books and even teaching a course at UCLA in the 1960s.

Among these admirable artisans was Dorothy B. Hughes, whose Ride the Pink Horse (1946) and In a Lonely Place (1947) were adapted to films that became prime examples of what was later called film noir. Hughes also wrote a discerning critical biography of Erle Stanley Gardner. She reflected thoughtfully on the conventions of crime fiction, reviewing books and even teaching a course at UCLA in the 1960s.

Perhaps her acute awareness of how thrillers manipulate viewpoint to maximize anxiety and to build up mystery led her to The Expendable Man (1963). It’s a wrong-man plot. Out of a spurt of kindness Dr. Hugh Densmore picks up a hitchhiking teenage girl on a lonely desert highway. She turns out to be reckless, manipulative, and obviously dangerous. Densmore lets her out at several points on the way, only to find her waiting for him further along. In Phoenix, where he’s come for his niece’s wedding, the young doctor learns that the girl has been murdered. He’s a prime suspect.

During his first police interrogation, Hughes casually drops in a shock that makes the reader reevaluate everything that’s led up to it–and feel not a little shame in the bargain. After this tour de force, Densmore’s struggle to prove himself innocent takes on a new pressure that adds enormously to the growing tension. Sorry to be so cryptic, but you have to read it in innocence to feel the diabolical force of Hughes’s scheme.

Margaret Millar, Santa Barbara. From “Margaret Millar Rediscovered,” Bay Area Reporter.

The Expendable Man locks us tightly to Densmore’s consciousness, while another book by a queen of suspense uses a wider-ranging narration. In Margaret Millar’s The Fiend (1964), a moving-spotlight narration reveals sharp criticism of how wives chafe under suburban routine.

Charlie Gowen spends his lunch hour sitting in his green coupé watching children in a playground. He becomes worried that one little girl takes risks on the jungle gym, and he fears that her parents are neglecting her. This concern grows to the point that he sends an anonymous letter to her mother. But he sends it to the wrong family. From this festers a plot of intricate lies, revelations, misunderstandings, and accusations that pulls in an entire neighborhood–friends, other kids, librarians, a lawyer, a pharmacist, Charlie’s caretaker brother, a would-be romantic partner, and of course the police.

Millar was a major crime novelist recognized in her day but now little-known. (Her fame was eventually surpassed by that of her husband Kenneth Millar, aka Ross Macdonald. I think she’s the better writer.) Her many first-rate suspense novels include A Demon in My View (1955) and Do Evil in Return (1950), a sensitive probing of a female doctor deciding whether to perform an illegal abortion. The Fiend sustains suspense to the very last page while offering portraits of children’s efforts to understand adult hypocrisy, and the various ways women cope with suffocating domesticity–not least, the obliteration of their identities. All this is given in a rich evocation of the milieu, down to the redwood picnic tables at a backyard barbecue and chipmunks scampering up lemon trees.

Unlike Millar, Patricia Highsmith was often underrated by American genre fans, while highbrow critics mostly ignored her. Fame has come to her more recently, thanks largely to popular film adaptations of her books (especially The Talented Mr. Ripley, 1999) and her tumultuous life as a Lesbian. Her personality, alternately fascinating and repelling, has too often distracted commentators from the power of her plotting and style. I try in Perplexing Plots to provide an analysis of some of her major storytelling strategies.

Her other books do not fully prepare you for The Tremor of Forgery (1969). It’s a crime novel in which the crime has the haziness of a mirage. Howard Ingham is in Tunisia starting to prepare a screenplay when his progress halts after the death of his producer in New York. He decides to linger and work on his next novel. That centers on an amoral, Ripleyesque bank executive stealing funds from accounts. In the real world, Ingham loiters, tours Tunisia, and strikes up friendships with a gay neighbor and a peculiar American propagandist. He also broods on whether his producer was having an affair with Ina, a woman he might marry. All this takes place against the background of the six-day Arab-Israeli war and the ongoing war in Vietnam.

Eighty pages in, Ingham takes a hasty action that may have resulted in a man’s death. By utterly limiting the viewpoint to Ingham, Highsmith keeps us in uncertainty about the consequences. The rest of the book plumbs Ingham’s mind as he tries to discover what he may have done and reacts to the responses of those around him. Highsmith’s finesse in keeping us in suspense about the exact contours of the incident releases her from what Henry James called “weak specification.” Instead she puts at the center of our attention Ingham’s fluctuating uncertainties about what he has done and should do.

The title refers to the telltale tremor in the sort of forgeries that Ingham’s embezzler Dennison commits. If it’s a symptom of guilt, it’s also a trace of Highsmith’s perennial theme of the instability of a person’s identity. Sometimes Ingham feels that he’s no more than all the opinions about him others hold. The Tremor of Forgery asks to what extent all our momentary roles are forgeries, and whether our moments of guilt and indecision betray a fundamental emptiness. At one moment, Ingham considers the possibility that “One was nothing anywhere, ever.”

As usual for the Library of America, these nine powerhouses are presented in elegant editions, filled out with plenty of authorial background and bibliographical sources. Just as important, this publishing initiative does a lot to dissolve that boundary between art and entertainment I objected to in an earlier entry.

Dead Calm (1989).

This entry was posted

on Monday | September 4, 2023 at 6:04 pm and is filed under Film and other media, Narrative strategies, PERPLEXING PLOTS (the book).

Both comments and pings are currently closed.