Poker Face, Ep. 10 (“The Hook”).

DB here:

Charlie Cale, an easygoing but tough young woman from New Jersey, has a unique gift. She can detect when someone is lying. She has exploited this in a career as an itinerant poker player, but after the word gets out about her ability, she winds up working as a waitress in a Las Vegas casino. A free spirit, she enjoys living from paycheck to paycheck, sharing beers and smokes with other staff. But the casino boss Stirling Ford Sr. learns of her gift and recruits her for a scheme targeting a rich patron.

That scheme collapses, and Charlie winds up having to flee across the United States. Driving the backroads, trying to stay off the grid, she keeps running into crimes in a wide range of settings. She stops at a Nevada Subway shop, a Texas barbecue joint, a stock-car race, a dinner theatre, a special-effects movie company, the venues of a touring heavy-metal band, a care facility for the elderly, and a remote mountain motel. We come to know each of these with remarkable specificity, noting details like lottery tickets and music amplifiers and Steenbeck flatbeds.

Charlie has the common touch. When she spots a lie, she’s likely to blurt out, “Bullshit!” She can freely talk and eat with working stiffs and is naturally suspicious of the plutocrats she keeps running into. She’s ready to deploy her ability to expose the less wealthy who want to exploit others. Eventually we come to learn that her sympathy for virtuous innocents may be compensation for her frosty relations with her family.

Charlie is the protagonist of Poker Face, a ten-episode series designed by Rian Johnson. Johnson is an admirer of classic mysteries. Earlier I’ve tried to chart his debt to Golden Age whodunits, as seen in Knives Out and Glass Onion. Unsurprisingly, he planned Poker Face as an homage and an updating of the TV show Columbo.

Charlie is the protagonist of Poker Face, a ten-episode series designed by Rian Johnson. Johnson is an admirer of classic mysteries. Earlier I’ve tried to chart his debt to Golden Age whodunits, as seen in Knives Out and Glass Onion. Unsurprisingly, he planned Poker Face as an homage and an updating of the TV show Columbo.

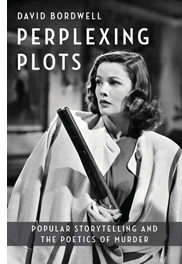

Apart from enjoying Poker Face on its own terms, I’ve admired its efforts to innovate. In my book Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder I argue that we have three useful tools for understanding plots. We can ask about the sequence of events in time; the way point of view structures our access to those events; and the way the events are broken into distinct parts. Noting how the plot handles time, viewpoint, and segmentation can help us grasp the ways Johnson has revivified the classic mystery–in ways that shape our experience.

I’ve had to indulge in spoilers, but I decided to confine those wholly to the first episode. Later episodes would justify a similar depth of analysis. And even in the first episode, I’ve tried to conceal major plot points when I could. In any event, I hope that people who haven’t yet seen the show (streaming on Peacock) might be intrigued enough to try it. It’s free although interrupted by commercials, but in a nifty use of segmentation Johnson manages to turn their timing to his advantage.

The inverted plot

Columbo, Ep. 1 (“Murder by the Book,” 1971).

The typical investigation plot begins with the crime already committed. The detective proceeds to unearth earlier events that led up to it. The alternative is, unreasonably, called the “inverted” plot. Here we witness the crime committed and perhaps are shown the motives involved. Then the detective arrives on the scene and we watch the investigator try to discover what we already know. We watch for slip-ups in what initially seems a foolproof scheme.

The inverted schema was developed most vividly in the Golden Age by F. Austin Freeman in a series of short stories. His sleuth, Dr. Thorndyke, arrives on the scene only after we have watched the culprit do the deed. The puzzle comes in trying to grasp how Thorndyke, using reasoning and scientific analysis, solves the mystery. In the process, he sometimes calls our attention to betraying details that we didn’t notice on the first pass.

This pattern of action comes off well in the short-story format, but it can be difficult to sustain in a longer tale. So the author may have the culprit resort to trying to impede or confuse the ongoing investigation, or to committing other crimes that need solution as well. These techniques come into play in Freeman’s novel Mr. Pottermack’s Oversight, which devolves into a battle of wits between Thorndyke and Pottermack.

A similar sort of stretching was common in Columbo, whose reliance on inverted plots inspired Johnson for Poker Face. The first episode broadcast, “Murder by the Book” (directed by Steven Spielberg), starts with disgruntled author Ken Franklin shooting his collaborator. Columbo, in his rumpled raincoat, doesn’t show up for the first eighteen minutes, and even after that he’s offstage during Franklin’s further schemings. These include creating a false trail for the crime and killing a witness who threatens him with blackmail.

We get some access to Columbo’s investigation behind the scenes, but the high points are his visits to Franklin. We enjoy the clash of slob versus snob when this obtuse flatfoot peppers the wealthy author with maddening questions–and always seems to accept a lie in reply. Eventually, when Franklin is trapped, Columbo reveals that he suspected him from the start; he just needed more evidence.

Despite its name, the inverted plot is usually linear. It traces events chronologically from crime to punishment, though flashbacks may provide chunks of backstory. This is where Johnson saw an opportunity to try something new. Assuming that viewers are familiar with the inverted plot schema, he juggles the sequence of events in unusual ways–exploring a different time layout in each episode.

A matter of timing

Poker Face, Ep. 1 (“Dead Man’s Hand,” 2023).

Except for the final installment, Poker Face follows the inverted schema: crime first, then investigation. But after we see the crime committed, the episode’s narration typically skips back and even “sideways” to show us circumstances leading up to the deed. Eventually the crime will be take its place in the chronological sequence–perhaps through a brief replay, or at least by reference in dialogue. Put another way, the crime segment is a kind of flashforward.

The first episode, “Dead Man’s Hand,” provides a tutorial in method. In a Las Vegas casino, the housekeeper Natalie finds horrific pornography on the open laptop of Kasimir Caine, a millionaire guest. She reports it to the boss, Sterling Frost Junior, and his fixer Cliff. They send her home. Cliff follows and shoots Natalie in her living room. He’s already shot her husband Jerry and he arranges the scene to look like a murder-suicide.

This block of brief scenes is followed by a linear story starting a few days earlier. Charlie works at the casino as a waitress, and she offers Natalie a place to stay after her drunken husband Jerry has raised a ruckus in the gaming room. In the meantime, Frost Jr. has learned of Charlie’s lie-detection talent and recruited her to watch Caine’s clandestine poker game by remote transmission. Frost will use her information about who’s bluffing in order to fleece Caine, while proving to his father that he’s a good manager.

Frost’s scheming with Charlie is interrupted by Natalie’s visit to report Caine’s pornography, so now the lead-in sequence falls into place. While Charlie is briefed further by Frost, Cliff is offstage killing Natalie and Jerry. The pivot is signaled by repeated dialogue: Cliff phones Frost (“It’s done”) and Frost resumes his explanation (“Where were we?”). The sequence of events is firmed up the next morning, when Charlie sees an online report of Natalie’s death.

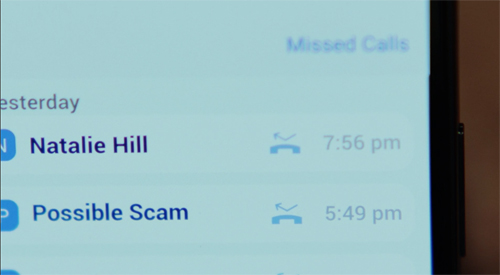

The rest follows chronologically. Charlie feels guilty for not returning Natalie’s call, made shortly before her death.

Her phone record leads her to notice disparities in the timeline and investigate, while she and Frost Jr. are preparing for the Caine scam. A slip of the tongue allows her to spot Frost’s lie about Cliff’s call, and he realizes she’s on to him. The result is Frost’s death and his father’s demand that Cliff capture Charlie. She flees and begins her backroads odyssey across America.

Later Poker Face episodes elaborate this template. Sometimes the crime is embedded in a large block of consecutive scenes, with all the backstory shown (ep. 2, “The Night Shift”). After that we skip back to still earlier events centering on Charlie’s travels leading up to the night of the murder, which takes place while she is next door in a tavern. That’s why I said that some of the scenes move sideways, showing incidents near her. This “proximity principle” is pushed further in ep. 3, “The Stall,” when Charlie is hovering just offscreen in the opening scene, as the murder conditions are laid out; the replay will reveal that.

Another variant: The leadup to the crime is extended for much longer than in the earlier episodes, with the murder coming a third of the way through the show’s running time (ep. 4, “Rest in Metal”) and the replay witnessed by Charlie over halfway through. Later episodes adopt mixed strategies. They still start with the crime, or at least the planning, and skip back in time, but they seed the later blocks with ellipses, brief flashbacks, and replays. It’s as if the series were teaching us week by week to accept an increasing flexibility in moving forward and backward and sideways, while still adhering to the basic convention of the inverted plot. We’re also helped, of course, by dialogue and intertitles telling us where we are in the timeline.

The exception to these pyrotechnics is the last episode, “The Hook.” It’s stubbornly linear in tracing Cliff’s pursuit of Charlie. It starts ab initio, with Frost Sr. ordering him to find her, and following that with scenes from earlier episodes in which Cliff misses her. In a way, this entire prologue is a kind of flashback that ends with him seizing her as she leaves a Colorado hospital. The final episode is the most conventionally readable because it isn’t an inverted plot. The crime is missing from the opening but is saved, as is common, for a climactic revelation.

What makes all this variation possible is a coordination of segmentation, viewpoint, and causal-chronological order. The blocks of time are dictated by attachment to the killer (s) or to Charlie. Typically the lead-up to the crime keeps us with the culprits. The flashbacks following the first statement of the crime are motivated because they’re attached to Charlie, who is just getting involved with the situation. The later segments are either purely tied to her, or (as in the Columbo episode) devoted to the culprit’s efforts to thwart her inquiry. In “Dead Man’s Hand,” for instance, scenes of her investigation are garnished with moments in which Frost Jr. and Cliff plan ways to circumvent her. In all, these maneuvers create pretty clever plots, their segments accented by the way that the end of a block tends to initiate a commercial break . . . just as in old network TV.

Charlie’s little gray cells

Poker Face, Ep. 8 (“The Orpheus Syndrome, 2022).

How good a detective is Charlie? Given her gift, shouldn’t sleuthing be utterly easy? Johnson has engineered his series to give her several handicaps that require her to sweat as much as any hardboiled dick.

For one thing, as a working-class woman of fairly slight stature, she starts by facing a bias in favor of the bulky, wealthy men (mostly) whom she challenges. In addition, after the first episode, she’s on the run and has to be discreet. Going to the police about anything would inevitably reveal her whereabouts to Frost Sr. Moreover, during her flight she’s deprived of what helped her crack the first case: her cellphone access to the internet. After Frost Sr. threatens that he will find her, she destroys her phone so she can’t be tracked. But now she’s got to rely on other sources of information.

Even her gift proves problematic. Unless a suspect explicitly denies committing the crim, her bullshit detector can’t know the person is guilty. Not incidentally, this condition puts a fruitful constraint on the screenwriters. They have to make sure the culprit’s dialogue circumvents the sort of declaration that Charlie would see through.

Confronted by all these obstacles, Charlie is obliged to act like a classic detective. Let’s count the ways.

For all the pledges to strict reasoning, the traditional sleuth is often triggered by intuition, the sense that something is just not right here. (The prototype is Chesterton’s Father Brown, but even logicians like Ellery Queen and Hercule Poirot are sensitive to “atmosphere.”) Charlie’s gift is an extravagant form of intuition, since it’s both illogical and impossible to explain scientifically, so even when it doesn’t expose the killer it can set off a minor alarm. In the season’s first episode, her suspicion is aroused when Frost Jr. lies about his phone conversation with Cliff.

The classic detective spots or unearths clues, traces of the criminal’s action and pointers to identity. Charlie’s case against Frost Jr. and Cliff in “Dead Man’s Hand” is built out of such traditional clues as a problematic timetable, uncharacteristic behavior (Natalie didn’t sign out when she left work), and hand dominance (would a leftie wield a pistol with his right?). Later episodes of Poker Face are packed with physical clues, from wood splinters to discarded candy wrappers. As Jacques Barzun puts it, in the classic detective story “bits of matter matter.”

Charlie is especially good at spotting the absent clue, the dog that didn’t bark in the night-time. In the first episode, she notices that video footage of Jerry hustled out of the casino shows him passing through Security unscathed.

But if he had his pistol with him, that would have been detected–which implies that Cliff kept it. Yet Golden Age conventions demand fair play: we must have access to all the clues the detective has. In his films Johnson has adhered to this, and he has in Poker Face. So we are shown the Security station in the casino twice earlier. Early on, Cliff breezes through, counting on the staff’s recognizing him and letting him pass.

Later, Charlie is stopped because her phone sets off the scanner.

Consequently, when Jerry doesn’t set off the alarm as Charlie had, he can’t be packing the gun.

Reasoning puts the clues together, but sheer reasoning isn’t enough to justify arresting somebody. There must be evidence. Charlie often finds herself convinced of the killer’s guilt but lacking something that would stand up in court. And without a cellphone she can’t resort to tricking the killer into confessing on a hot mic. Yet some solid evidence is needed to clinch the case. The screenwriters have been ingenious in finding other damning records. Episodes recruit heart-monitor charts, 16mm film, CCTV footage, and digital audio and video captured by Charlie’s helpers or the culprits themselves.

In a classic whodunit, as we approach the climax, the detective is often blessed with a stroke of good luck that advances the solution of the puzzle. It’s often something apparently trivial–an overheard conversation or a slip of the tongue, or an irrelevant detail that inspires the detective to reinterpret a clue. In “Dead Man’s Hand,” Charlie spots the TV report of Jerry passing through Security not by diligent research but by sheer accident. She’s just dropped by the bar when the broadcast appears.

One more convention, one that the series adopts gradually: an alliance between detective and law enforcement. The classic detective cooperates to some extent with the police, either wholeheartedly (Queen, Poirot, Lord Peter Wimsey) or grudgingly (Nero Wolfe). Even tough guys like Sam Spade, Nick Charles, and Philip Marlowe may exchange information with their friends on the force. At the start of Poker Face Charlie is a loner, but as the series proceeds, she gain an ally in the FBI, and because she helps him crack cases he comes to her aid on occasion. “At this rate, if I stick with you I’ll be head of the Bureau in a year.”

In all, Poker Face has engagingly modernized the inverted plot schema while benefiting from classic principles. Those permit the detective to show off powerful intuition, systematic reasoning, and Machiavellian cleverness in trapping the prey. In addition, the series has added to the gallery of admirable sleuths a hard-boiled but compassionate wise-guy woman. And it’s done with a strong dose of social criticism. This have-not from Jersey wreaks vengeance on those who victimize innocents.

Poker Face is scheduled for a second season, with Charlie once more on the run across America. We may expect that it will continue to show how ingenious play with time, viewpoint, and segmentation can revivify conventions of the whodunit. Keen fans learned to ask not only How will Charlie discover the crime we’ve seen committed? but also ask, with a teasing meta-curiosity: What ellipses and time jumps and hidden clues will we get this episode? Johnson seems unlikely to give up the game any time soon.

In Deadline, Antonia Blyth provides a very informative interview with Rian Johnson and Natasha Lyonne about Poker Face.

Martin Edwards discusses the inverted plot schema as part of a broader trend toward empirical, scientific investigation techniques in The Life of Crime (2022), Chapter 10. For a thorough survey of Freeman’s work, see Mike Grost’s discussion. Jacques Barzun emphasizes the role of physical clues in his superb essay, “Detection and Literature,” The Energies of Art: Studies of Authors Classic and Modern (1956), 313.

I discuss the inverted plot in more detail in Chapter 5 of Perplexing Plots, considering it as a hybrid of the pure investigation plot and the psychological thriller.

Poker Face, Ep. 3 (“The Stall,” 2023).

This entry was posted

on Sunday | June 25, 2023 at 8:14 pm and is filed under Directors: Johnson, Rian, Narrative strategies, PERPLEXING PLOTS (the book), Television.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.