Widely praised as a lush and astute treatise on the relationship between artist and muse and also as a portrayal of toxic masculinity, Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film, Phantom Thread, could perhaps be read from a psychoanalytical perspective as drama of Bergman-esque proportions exploring a perverse love story.

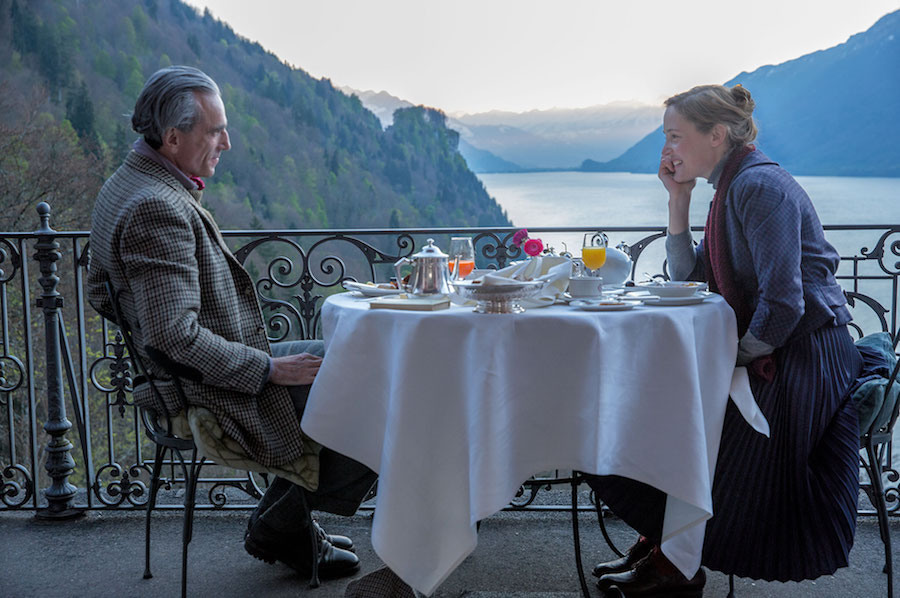

Reynolds (Daniel Day-Lewis) and Alma (Vicky Krieps) in Phantom Thread (2017). Courtesy Focus Features.

Enter Reynolds Woodcock—played by Daniel Day-Lewis in what’s supposed to be his last role—a successful couture designer of 1950s London, dressing high society women from his Fitzroy Square atelier. We learn quite a bit about Woodcock: he’s talented in the tormented way usually reserved for the visual artists of that period; he is prone to mood swings and has neurotic habits in the form of a desire for space and silence; he’s a handsome bachelor, successful with the ladies but unable to engage on a deep emotional level because the woman of his life, we find out early on, is his late mum. No one in the string of conquests that come and go through of the doors of the house of Woodcock can ever replace his mother, who—crucially—taught him how to sew, and whose wedding dress he himself designed and crafted at the tender age of 16.

Consequently, emotionally detached and repressed (wooden, one could even say), Woodcock is quite lonely. Begrudgingly, he attends the fancy dinner parties and social occasions that befit his profession and clientele, but he finds them boring and exhausting, preferring to have dinner in his favourite restaurant alone with his sister Cyril—a brilliant Lesley Manville—with whom he lives and works.

It is when Woodcock goes to the countryside, escaping from the city after an intense bout of work, that he meets German waitress Alma ( a name which, fittingly, translates as “soul” in Spanish). Their very first encounter—which according to film lore was also the first time the two actors, Day-Lewis and Vicky Krieps saw each other—is electrifying. There’s intense onscreen chemistry: she is clumsy but charmingly defiant; he’s overconfident, but charmed. A dinner date ensues, during which he talks passionately about his mother (uh oh) and asks Alma to undress and model for a dress. Woodcock then fits the dress for her, with the help of Cyril, who arrives promptly to the scene to resume her role of stoic (and stern) third wheel, literally sniffing Alma like a dog upon arrival.

It’s a creepy, intrusive and intense start to things, a harbinger of the dynamics that the Woodcocks will expect to continue in London. Alma promptly moves there, to work as both model and paramour at Woodcock’s will. She’s installed in the room next door to his, almost half concubine half maid. One of her non-negotiable tasks is to remain quiet at breakfast. Loud crunching and clanking will not be tolerated as it disturbs the master as he is getting mentally ready for work (some of the film’s best scenes are of these fraught, cringe-worthy breakfasts).

Reynolds (Daniel Day-Lewis), Alma (Vicky Krieps) and Cyril (Lesley Manville) in Phantom Thread (2017). Courtesy Focus Features.

Alma initially agrees to it all through gritted teeth, but you can see her rebellious soul begin to emerge soon after. The more autonomy she tries to carve for herself, the more determinedly Cyril and Reynolds stifle it. She loves Reynolds, she wants to spend some time alone with him, which seems absolutely impossible in that household of Ibsen overtones. The birthday dinner scene is the film’s pièce de résistance: it is superbly acted, Day-Lewis intolerant and nasty, a superb Krieps coming undone, raw, humiliated and powerless.

Until she’s not, because Alma finds a way to assert some control over that power imbalance. The build up to the revelation of how she manages to do that that is packed with tension and suspense, in which other critics have found echoes of Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940). Which is why the final revelation and denouement feel rushed and almost banal. It’s like the film is a perfect masterpiece until the last 20 minutes, in which a tense and powerful chamber piece is turned, somewhat flippantly, into a black romantic comedy.

Reynolds (Daniel Day-Lewis) and Alma (Vicky Krieps) in Phantom Thread (2017). Courtesy Focus Features.

I left the cinema feeling frustrated with Phantom Thread, wanting to be in love with it for all its technical mastery, but not being able to shake a sense of disappointment. Until it suddenly hit me why: Alma has almost no character development. We see her fierce personality and her outlandish yet effective actions, but we don’t know who she is, why she left Germany for the UK, where her risky ideas come from, why she signed up so swiftly to a claustrophobic arrangement with a rich and talented man who is nevertheless a complete stranger. Is she perhaps a WW2 refugee? Did she lose her family in the war and is now looking for a sense of attachment and security wherever she can find it? Why is love a matter of life or death, literally, for Alma?

I think that is the problem with Phantom Thread, which feels in love (and in line) with great psychological dramas like those created by Bergman, yet it seems afraid of getting down and dirty with the actual mess of the details, with the origins of fixations, identifications and pattern repetitions that explain symptoms and behaviours, and thus make cinema feel real and mirror life.

Reynolds (Daniel Day-Lewis) and Alma (Vicky Krieps) in Phantom Thread (2017). Courtesy Focus Features.

When Woodcock is ill and bedridden the first time, he hallucinates her mother as a young bride in the dress he made her. It is a poignant moment, as people close to death often see or speak with their beloved departed relatives. Then Alma enters his room, and for a moment mother and lover are next to each other, almost superimposed; love, desire, containment and power struggles all conflated in one perversely effective jumble.

It is such a powerful set up. It has so much to say about gender roles and expectations, about the need of asserting control and of learning to let go, about the difficulties of keeping a long-term relationship alive and how love is based on learning to trust and to forgive, over and over again. Yet, because of its rushed ending and lack of investment in the background and motives of Alma, it feels as if Phantom Thread was a film of ideas in which the ideas have been buried under a thick layer of silk and lace, as beautiful as it is obstructive.