Following is an overview of some of Callas’s career highlights at La Scala.

“Aida” (Verdi): April 12, 1950

Callas’s very first performance onstage at La Scala was as a substitute for the much-adored Renata Tebaldi, who was unwell. It was, by all accounts, a tepid debut. A skin condition had given the 26-year-old soprano facial blemishes that she awkwardly covered with veils. In “Maria Callas: An Intimate Biography,” by Anne Edwards, the director Franco Zeffirelli (who would go on to work with Callas) recalled “this overweight Greek lady, peeping out from behind her trailing chiffon,” with an “unevenness” in her voice. Her two remaining performances of “Aida” went much better, but this inaugural “Aida” was a blow to the young prodigy’s self-confidence.

“I Vespri Siciliani” (Verdi):

Dec. 7, 1951

This was the first time that Callas was headlining a La Scala production — kicking off the opera house’s season, in fact — and it was a triumph. She was understandably nervous at the start. “The miraculous throat of Maria Meneghini Callas did not have to fear the demand of the opera,” the music reviewer Franco Abbiati wrote in the newspaper Corriere della Sera (according to the biography “Maria Callas: The Tigress and the Lamb,” by David Bret). Mr. Abbiati lauded the “phosphorescent beauty” of her tones, and “her technical agility, which is more than rare — it is unique.”

“Lucia di Lammermoor” (Donizetti): Jan. 18, 1954

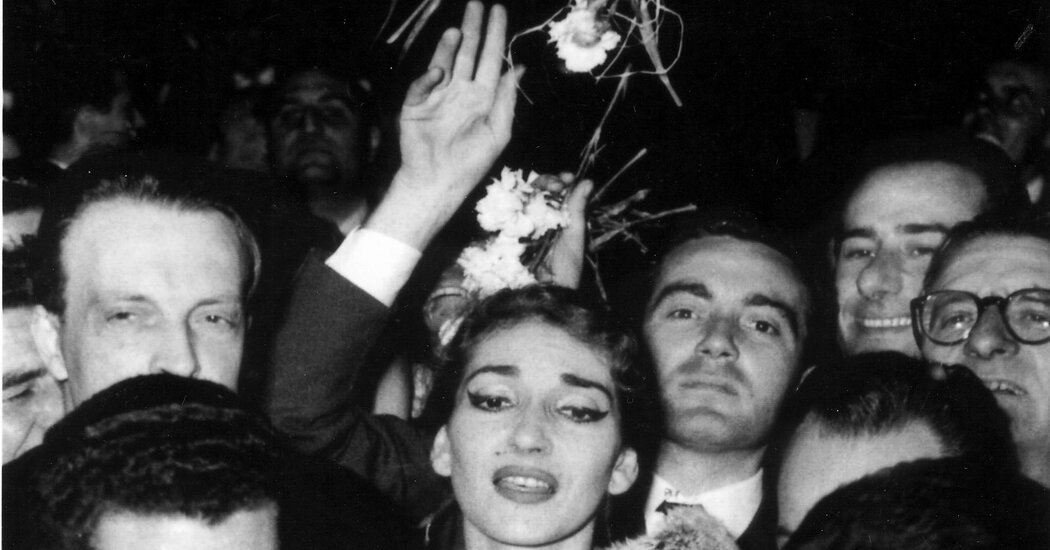

This was Callas’s first time with the renowned conductor Herbert von Karajan at the baton, and she didn’t disappoint. In the famous “mad scene” — where Lucia stabs her new husband on her wedding night — Callas appeared barehanded, in a nightgown and messy hair, on a dimly lit staircase; she had turned down the dagger and fake blood that are usually used to portray the murder. Yet her performance was so realistic that mesmerized audience members jumped up mid-performance, clapping and cheering, and tossed red carnations onstage that Callas touched as if they were gobs of blood. In Opera News, the critic Cynthia Jolly hailed “Callas’s supremacy amongst present-day sopranos,” and “a heart-rending poignancy of timbre which is quite unforgettable,” according to the Bret biography.

“La Traviata” (Verdi): May 28, 1955

The character of Violetta in “La Traviata” is widely considered one of Callas’s three finest roles — along with Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor” and Bellini’s “Norma.” And the May 1955 staging by the director Luchino Visconti is, in turn, considered her finest “Traviata.” It was “a revolutionary production” that was “renowned for its realism, the intimacy and the gorgeousness of the setting, the painterly qualities,” said Mr. Fisher of The Times. It also “encapsulated so much” of the Maria Callas that audiences have come to know and revere. Set in La Belle Epoque, with ornate décor and costumes, the show triggered another audience frenzy on opening night. People cried out Callas’s name, sobbed uncontrollably and showered the stage with red roses, which a tearful Callas picked up as she took a solo bow. The conductor Carlo Maria Giulini later confessed that he, too, had wept in the pit. Yet Callas’s monopolizing of attention in her solo bow was too much for the tenor Giuseppe Di Stefano, who quit the show that night.

“Anna Bolena” (Donizetti):

April 14, 1957

This was another Visconti spectacular, and another triumph. Callas played Anne Boleyn, a doomed wife of Henry VIII, in a somewhat lesser-known Donizetti opera. Queenlike, she appeared in a dark blue gown and enormous jewels at the top of a grand staircase, surrounded by royal portraits. Musically, she gave it her all, triggering 24 minutes of applause (according to the Edwards biography), a La Scala record.